Fortune News | Nov 02,2019

Dec 11 , 2020.

Few policies in Ethiopia irked liberal economists and multilateral institutions as the bills private banks had been compelled to purchase. At 27pc of the gross loans and advances they make with the intent of redirecting public savings mobilised by private banks to areas the state deemed development priorities, it was mandated by the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) in 2011. For eight years henceforth, multilateral financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) implored Ethiopia's government to do away with this policy.

A new administration, with Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) at its helm, listened. From the start, the fresh faces in the Prime Minister's economic team were decidedly liberal-leaning on the economic front and not a fan of the developmental state model of his predecessors. Touted by Western backers, the young policy wonks such as Eyob Tekalign (PhD), Fitsum Assefa (PhD) and Mamo Miheretu had the better part of the Prime Minister over veterans such as Girma Birru and Teklewold Atnafu.

With external debt mounting, inflation on the climb, and several major projects almost stalled, the heeding of Abiy and his liberal enthusiasts was not met with a strong challenge when he reoriented the direction of the economy. Even plans to privatise major state enterprises, including the national carrier, were more vocally challenged in the name of patriotism than advocacy of the previous economic model.

High up on the agenda, or at least among the top brass, was “ending financial repression,” as the IMF refers to it. The triumvirate toward this goal was eliminating NBE's bills, issuing more treasury bills (T-bills), and reducing borrowing from the central bank. These three go hand in hand. Without a continuous injection of funds collected from the forced sale of the NBE bills, the belt needs to be tightened, lessening state involvement in the economy. Issuing more T-bills would cover gaps in spending needs, aka the budget deficit. It is healthier than borrowing from the central bank. So it was thought.

The new administration obliged. The NBE bills were eliminated, and the T-bill bonds were floated in a bid to incentivise their sale. It was a prudent change of policy for which the central bank deserved credit. Without any more NBE bills harvested from private banks - 116 billion Br by last year - it would surely force the government to rethink spending.

Opening up the domestic T-bill market was even more revolutionary. At the time, its yield stood at 1.7pc despite double-digit inflation and an average savings deposit interest rate of eight percent. It was not profitable. Banks knew it. The government also knew it but did not mind given that it had a captive market. The social security agencies and the Development Bank of Ethiopia (DBE) were its main customers. It was a market that the state borrowing heavily from the central bank and forcing private banks to buy bonds could not care enough to look into.

Floating the T-bills has already paid off, at least in as far as making it a viable market that also helps in closing short-term budget deficits was the goal. It incentivises buying. No doubt, it also means a higher payout for the state. But a commiserate reward to the Finance Ministry, on whose behalf the central bank issues the bonds, would only have been possible under market rules had other variables been factored in, such as inflation.

That the T-bill market has brought not as much as what was hoped for became obvious. Look no further. When the central bank comes around with a new directive forcing insurance companies to spend 40pc of their admitted assets on T-bills, it is an admission of failure. Its officials, notably its Governor, Yinager Dessie (PhD), are sliding back into “financial repression.” By the action, the bank is not hiding its intentions - it was to enlist help in monetary policy. This is not a move far removed from the NBE bills that came to an end last year.

The forcing of investments in T-bills marks a contradiction in economic governance and policymaking. It is a sign that the administration is finding it hard to manoeuvre with meagre resources and discipline its own spending. There is hardly a better illustration of this than the continued utilisation of what are supposed to be profit-making enterprises under the management of the state for policy purposes. The most prominent of these is the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), a state commercial bank that has long been serving as a de facto policy bank instead of an enterprise that operates according to market rules.

The current administration, for all its promises to make the private sector a close partner in development initiatives, has continued the tactics of its predecessors when it comes to spending needs. Recently, the CBE donated 1.1 billion Br for “Dine for Nation,” a programme aimed at raising funds for three projects in the country. The CBE covered over a third of the funding that the programme hoped to raise, once again performing the duty of a policy bank and serving the administration's indulgence in the aesthetic.

Beauty, wrote Edmund Burke, is far from showing the vitality of power but its decadence. It leads to indifference or total dissolution of the self.

"Our most salutary and most beautiful institutions yield nothing but dust and smut," said Burke.

Understandably, an administration that was propelled to political power at the back of pledges to bring fiscal and monetary discipline has been challenged with a threat to public health that is a global pandemic. The urgency of the change of plans was felt in the federal budget it passed; at 476 billion Br, it is the highest the country has ever seen, indicating the inability to tighten the belt. It was prudent of an administration faced with an economy destined to slow down as a result of the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

Unfortunately, appreciating the gravity of the challenge does nothing to alleviate the fact that the economy is being mismanaged. Stuck with a policy designed to open up the economy and tighten the belt, the administration nonetheless has had to continue to allow its intrusive hands in the economy. Bad habits die hard. As the administration continues to dilly-dally, the economy is becoming a contradiction in terms.

The consequence of this is lower-income groups being squeezed to their limit. With year-on-year inflation stuck around a stubborn 20pc, cash is being taken directly out of the pockets of those that desperately need it to put food on the table.

Not all hope seems lost, nonetheless. There are some cards those in the administration can still play. For starters, they should cease bullying the private sector whose sole rationale for existence is to make profits. The government is facing a hard decision between having to stimulate the economy while still bringing the supply of money down. Tightening the belt then is only possible by identifying priority projects and suspending the kinds of projects Burke would describe as "potent symbol[s] and agents of degeneration."

In the eyes of many, least of all the Prime Minister, the projects that the “Dine for Nation” programme targets to fund are not unimportant. But they should be allowed to be carried out through their organic process. It is the improvement of the political situation in the country as well as the business environment that incentivises individuals and enterprises to engage in productive sectors with the most optimal use of limited resources. When the CBE fills the gap in finance, it distracts from its core purpose. More importantly, it distorts the market signals that help assess the private sector's confidence - information the state needs to design economic policies. It also crowds out finance for the private sector.

Complicating the tolerable intervention the state may make in the economy is the accelerating devaluation of the Birr. Between October 2017 and November 2019, the currency tracked from 27 Br to the dollar to 29 Br. But in the course of just over a year, it depreciated by over a third of its amount - 38 Br to the dollar.

It is one thing for the state to gradually edge the Birr toward a market-clearing rate compared to a basket of other major currencies while it tightens its belt. It is quite devastating for consumers, however, when it continues to not relent in its spending while at the same time gradually lowering the value of the Birr. Seeking to do both is crushing consumers, whose purchasing power is being wiped out on two fronts: depreciation and inflation. This in turn affects aggregate demand the state needs for the stimulation of the economy.

In the absence of the administration's resolve to let the market determine the value of the Birr, its managed depreciation may slow down until at least the current economic crisis - brought on by the pandemic and political uncertainty - ends and the state can have the courage in its conviction to be more austere. Otherwise, low fixed-income households will continue to shoulder the burden of galloping inflation. Coupled with a weakening purchasing power of the Birr, many families will find it hard to put food on the table.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 11,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1076]

Fortune News | Nov 02,2019

Radar | Jan 27,2024

Commentaries | Apr 26,2019

Radar | Feb 27,2021

Fortune News | Feb 09,2019

Commentaries | Aug 08,2020

Sunday with Eden | Feb 06,2021

Viewpoints | Apr 22,2023

Fortune News | Oct 03,2020

Fortune News | Jun 12,2021

My Opinion | 108818 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 105216 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 104028 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 103320 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transportin...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

The cracks in Ethiopia's higher education system were laid bare during a synthesis re...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Construction authorities have unveiled a price adjustment implementation manual for s...

Jul 13 , 2024

The banking industry is experiencing a transformative period under the oversight of N...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

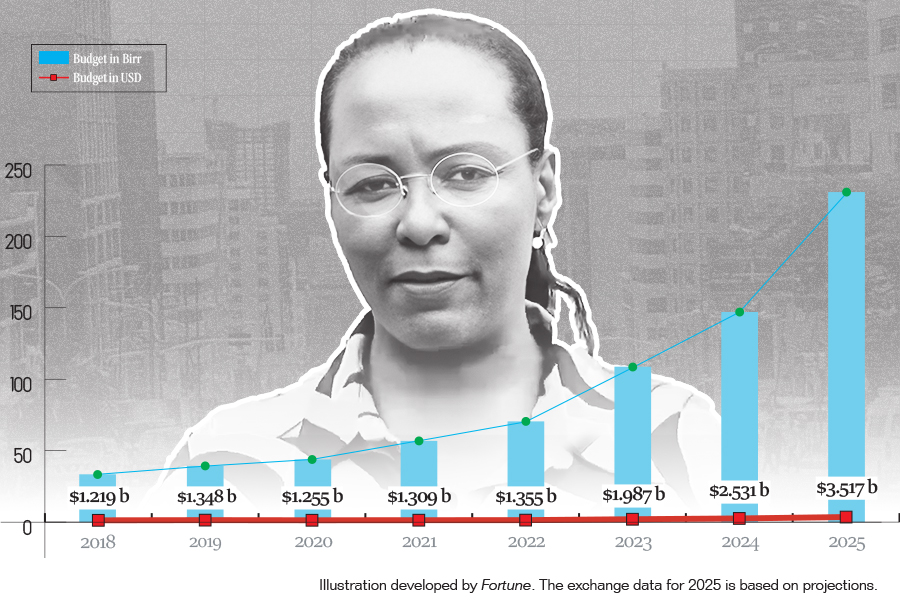

Mayor Adanech Abebie's Administration faced an audit report that unveiled a startling...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Brook Taye (PhD), director general of the Ethiopian Capital Market Authority, has tak...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's horticulture, a major source of foreign currency and employment, is facing...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Commercial banks are now permitted to acquire equity shares in capital market service...