Editorial | Oct 28,2023

Aug 21 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

Gig working gets a bad reputation. This makes sense considering that much of the debate takes place in the developed world, and narratives are constructed from the perspective of the Global North.

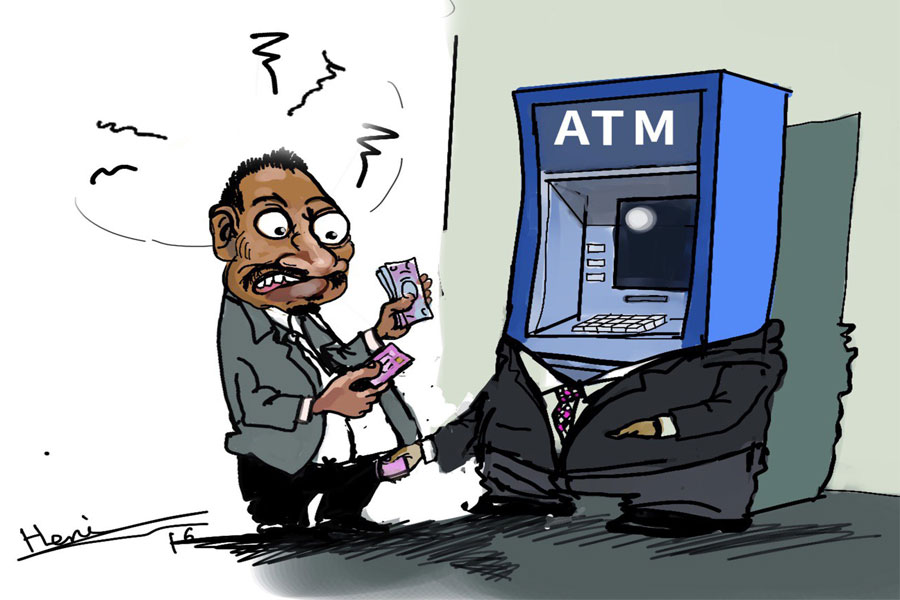

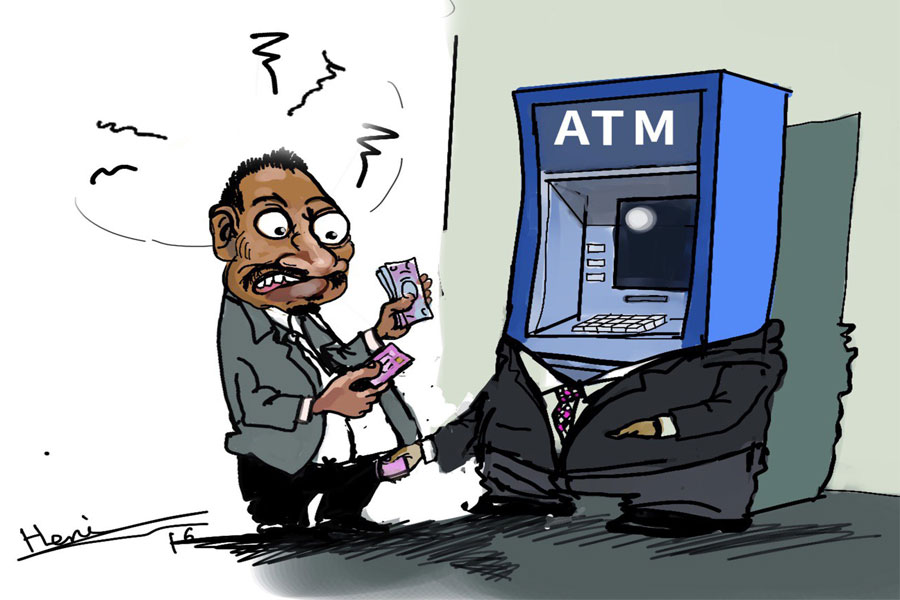

Gig workers are basically independent contractors. There is work to be done, and they have a job; there is not and they are out of luck. They have always existed in the form of temporary employees at companies or as labourers that get paid daily either in construction or on farmlands during harvest seasons. But the number and importance of gig workers has exploded with the growth of the internet and digital economic sectors.

Some sources suggest that as many as 163 million gig workers are registered on online labour platforms such as Upwork, Freelancer and Amazon Mechanical Turk. Unregistered freelancers are bound to bring the number even higher. The size of the gig economy is estimated to be 347 billion dollars, over three times Ethiopia’s GDP, while the number of gig workers earning above 100,000 dollars a year has reached 31 million people of the labour force, according to Brodmin, a fintech company. The average worldwide hourly rate charged by freelancers is around 21 dollars, comfortably above minimum wage in the United States.

A good example of gig workers are ride-hailing service drivers. While the debate between whether such drivers are hired employees or independent contractors has gone to the courts, the concept behind it is clear. Each driver makes a rate based on the trips they can make and does not have salaries from the company they are contracted out to for the work.

As flexible and unique as gig economy is, it is not that much cherished. There is a reason for this: economic security. The working time may be flexible, but financial security is not guaranteed. There are no benefits, healthcare plans or severance pay under normal circumstances. If there is an economic downturn, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and employers want to cut costs, a gig worker is out in the cold without anything to cushion the blow from the company that contracted them out.

There is space for this debate in the developed world. There is not one in a country such as Ethiopia.

It starts with the nature of employment. Most people are often underpaid and usually see their wages decrease in value as inflation is a recurring problem. Even in good times, when inflation is kept in the single digits, a person’s wage needs to grow by at least 10pc to be comfortable that they are not working for lower and lower pay by the day. Losing a job is relatively not too much of a blow.

Then there is the fact that benefits are little to none. Companies providing healthcare as part of employment are nearly unheard of, while severance pays often do not materialise as there is high turnover in most industries. By migrating to the gig economy, employees in Ethiopia do not lose as much.

But people could gain much more by becoming gig workers. The most important aspect is flexibility. Most traditional work in Ethiopia is spent sitting around in the office doing nothing. In the same time frame, much freelance work can be squeezed in to make up for the difference in salaries. No doubt, gig workers will still be financially insecure, but for those with the skills and credentials, it can be made up for by using one’s time smartly and consumption smoothing to prepare for the rainy day.

Gig working is not for everyone and is entirely out of the question for professions in sectors such as healthcare. But it is a refreshing alternative to the drudgery of traditional employment. The key to reaping its fruits is accumulating skills, experience and networks. What underlies the gig economy is the increasing importance of the knowledge economy. This is work that can be outsourced anywhere and done from any location. But one thing that cannot be substituted is the skills and experience accumulated through education and hard work.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 21,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1112]

Editorial | Oct 28,2023

Commentaries | Aug 19,2023

My Opinion | Jun 21,2025

Addis Fortune | Jul 03,2025

Editorial | Jun 21,2025

Commentaries | Dec 16,2023

Fortune News | Oct 21,2023

Editorial | Oct 05,2024

My Opinion | Jun 07,2025

Commentaries | Apr 17,2021

My Opinion | 131983 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128372 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126309 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123927 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...