Fortune News | Mar 14,2020

Jul 30 , 2022

By Christian Tesfaye

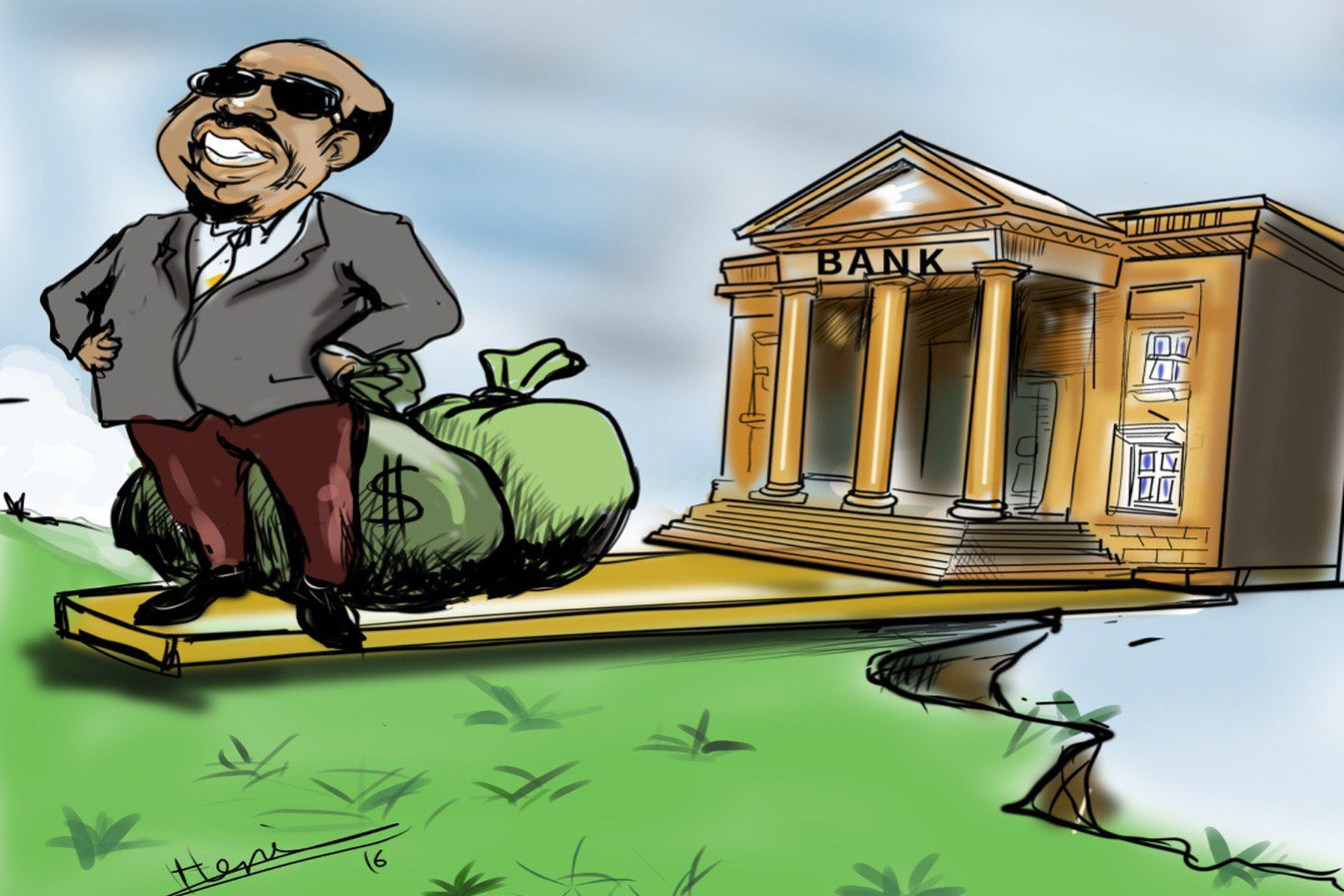

It seems that there is a new bank opening its doors every week. The latest was Tsehay Bank, which commenced its operations with a ceremony as its headquarters last week. A week before that was Ahadu Bank, and Amhara Bank about a month earlier. Over the past year, ZamZam and Hijira banks, full-fledged interest-free banks, have entered the financial sector.

The banks are similar. Most will primarily focus on retail banking, racing to mobilise deposits, lend to very few of their clients (especially in the export business) and conduct business through brick-and-mortar outlets. They do not bring much new to the table; if they will, it is yet to be seen.

But there is one element that is interesting about them: shareholder base. Ahadu, ZamZam and Hijira are somewhat similar. They all have about 10,000 shareholders raising subscribed capital in the low billions of Birr, except for Ahadu’s 702 million Br. Nothing much out of the ordinary. Tsehay and Amhara banks are another story.

Tsehay has only 373 shareholders, who have contributed 734 million Br in paid-up capital, and signed up for 2.9 billion Br in total. When all the subscribed capital has been fully paid up, around eight million Birr would have been raised on average from an individual shareholder, owning about 0.27pc of the shareholder equity. This makes Tsehay’s shareholders one of the least diluted in the banking industry.

On the other end of the spectrum is Amhara Bank. Its website puts the number of shareholders at 169,000, the highest among any bank in Ethiopia. Its subscribed capital is 6.5 billion Br, which puts the average individual contribution at a little over 38,000 Br when fully paid. The average ownership stake in the bank is highly diluted.

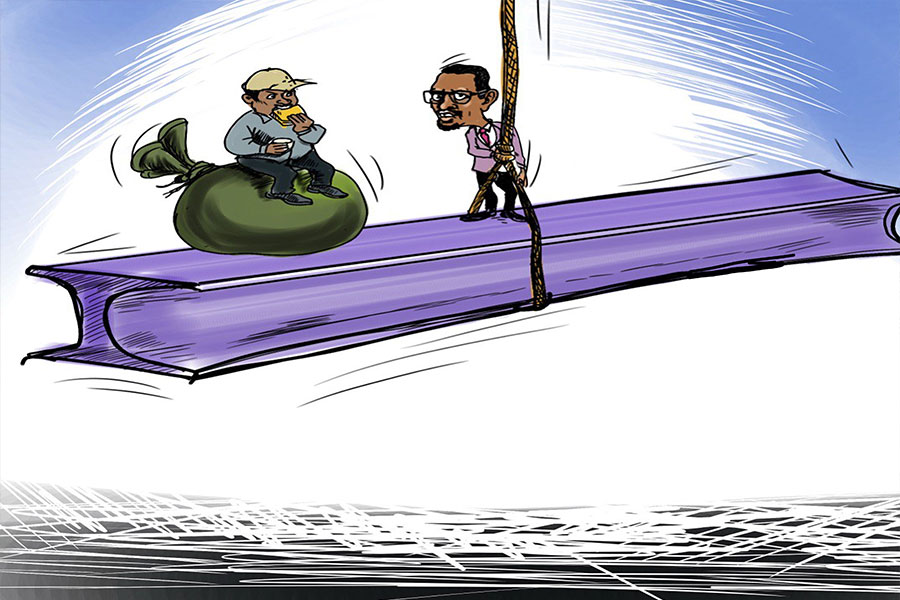

Is there a point to all of this, especially to the bank? Too many shareholders or too few, which is better?

There are both good and bad in either equity financing strategy. In the case of Amhara Bank, its large number of shareholders give it an edge in mobilising deposits. Say that each shareholder chooses to save at the Bank 1,000 Br on average; this is 169 million Br. If five more of their friends, family or relatives save just as much on average, this is 845 million Br in deposits mobilised using the shareholder network alone.

Being Tsehay Bank has its advantage as well. A low shareholder base means stakeholders whose interests can be reconciled and can easily agree on strategies and business models. It helps management be more flexible in manoeuvring within the market. Most shareholders are also likely high net worth (again, going by averages). Thus, dividend distribution would not be as salient as overall shareholder wealth maximisation. Profits can be reinvested without too much worry.

All of this will become more important as a stock exchange is introduced and banks are listed. Companies have specific shareholder management policies based on financing requirements, capital structure and current market price. Some want to have many and others less.

Take a recent example. Amazon, listed in the US, split its stocks 20-to-1, from about 2,000 dollars a pop to around 125 dollars (the discrepancy in the numbers is due to other facts that affect stock price). Why? Stock splits are carried out mainly to increase shareholder numbers, especially the share of retail investors. People who cannot afford 2,000 dollars have a chance to own an Amazon stock for a bit over 100 dollars. It is also to reflect the real price of a stock better. The more investors there are trading a share, the better the price discovery.

Others go in the opposite direction. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, a holding company, has an individual share trading at half a million dollars. It has much fewer shares outstanding for a publicly traded company its size. Only high-net-worth individuals (like Warren Buffet himself) and institutions (like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) have the financial capacity to trade in Berkshire’s stock.

It is also not a surprise that the holding company does not pay dividends, despite sitting on a 144 billion dollar cash pile, according to its 2021 report. All dividends are reinvested. Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholder base is not retail investors, who need liquidity from investments for non-discretionary spending, but investors that seek long-term capital growth.

Neither Amhara nor Tsehay bank’s strategy is wrong. All that matters is that there is a well-developed game plan behind it.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 30,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1161]

Fortune News | Mar 14,2020

Radar | May 23,2020

Radar | Aug 22,2020

Radar | Aug 26,2023

Radar | Aug 05,2023

Radar | Mar 25,2023

My Opinion | Nov 04,2023

Radar | Nov 26,2022

Sponsored Contents | May 22,2023

Fortune News | Jul 11,2021

Photo Gallery | 96843 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 89065 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67202 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65771 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 20 , 2024

In a departure from its traditionally opaque practices, the National Bank of Ethiopia...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Apr 20 , 2024

Ethiopia's economic reform negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in their fourth round, taking place in Washington, D...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By BERSABEH GEBRE

An undercurrent of controversy surrounds the appointment of founding members of Amhara Bank after regulat...

An ambitious cooperative housing initiative designed to provide thousands with affordable homes is mired...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's juice manufacturers confront formidable economic challenges following the reclassification of...