Apr 9 , 2022.

The heartbreak from Ethiopia’s civil war has not abated. Not even close. A few months shy of its second year, the war has induced a new chapter in almost three decades of relative peace and economic growth. In some parts of the country, decades of economic and human development gains have nearly been wiped out. Now the risk to rip the country apart has passed the hypothetical stage.

The overwhelming despair felt far and wide appears to temp many to give up hope on the prospect of peace if it was not for the rare flicker of light that appears from time to time. These were most evident from the "unilateral ceasefire" declared at different times before the conflict accelerated once again. The most recent is a "humanitarian truce" the federal government announced last month. For the first time, a gesture of truce was reciprocated by armed forces in Tigray. It reveals that there could be talks and understanding between them before such public pronouncements were made. It is yet the most promising, even if the reality on the ground has not moved much past rhetoric.

The "truce" comes in the wake of crucial steps already being taken. The most significant was the release of prominent political figures from jail, which seemed to come from nowhere for many and led to some backlash. It is a desirable outcome in the effort to re-establish goodwill and trust between the warring parties of various groups. Notable was also a policy paper released to the rank and file of the ruling Prosperity Party (PP) declaring its commitment to resolve the militarised conflict in the north peacefully. Considering that the incumbent party controls every office of authority at regional and federal levels, getting buy-in along the power structure is vital.

Perhaps none of these matter as much as the urgency to accelerate humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected areas. In a rare missive, officials and multilateral organisations have sounded positive developments in deliveries in the past few days, although what is needed given the scale of the tragedy is much more significant. It should be an unforgivable vice to play power politics over the suffering and misery of the civilian population, including children. A meaningful breakthrough in responding to the humanitarian catastrophe would be the most concrete evidence, perhaps even more than a comprehensive ceasefire, that the war could end soon.

Nonetheless, there is still a long way to get to peace. The battle for peace is more elusive and frustrating than the fleeting victory on the battlefronts.

An apt analogy would be a famous statement made by Winston Churchill following a military breakthrough in North Africa against the Germans in the Second World War: “Now, this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

The same may apply to this dark chapter in Ethiopia. In this case, the optimism does not come from any battlefield successes. Hoping against hope, however small and seemingly extrinsic, there are encouraging steps that could contribute to the realisation of peace in a country where peace has a few friends.

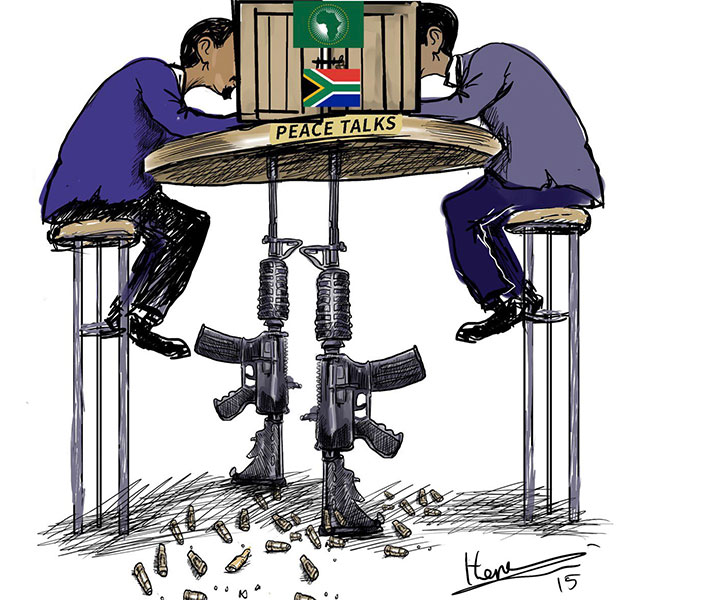

The main challenge yet to be overcome is the inability of all parties to reach a comprehensive ceasefire to silence the guns and a formal start to a peace deal. Such developments of vital importance remain chimaeras, even as it becomes evident that nothing but suffering and collective trauma will be the legacy left behind by the civil war. While there are "encouraging" signs that the warring parties are moving, however stubbornly, in a positive direction, the essence of time is given very little attention. The longer the conflict festers, the deeper the bitterness and acrimony among people outside of the active groups doing the fighting.

The conflict has already raged for over a year and a half – far too long, considering the civilians caught up in the crossfire. The longer it continues, the harder it will be to end without planting the seeds of mortal enmity. There are two significant reasons for this. It has to do with the humanitarian disaster and how politics functions.

Start with the humanitarian tragedy. In some ways, the conflict has been a "total war." Given the extent to which atrocities against children, women and the elderly have been committed and civilian infrastructure targeted, combatants have not been the only ones dying on a large scale. Millions of citizens now have family members, relatives or close acquaintances killed due to the wars. The more the bodies pile up, the less likely it would be that enough goodwill could be mustered for peace to hold sustainably.

The evolution of political circumstances will also matter. War has momentum, as conflicts worldwide and in Ethiopia have shown. The longer it persists, the more it will be entrenched within the political structures of the conflicting sides. Soon, the tragedy and crisis become a status quo, especially as a political class emerges on either side whose influence and status are tied with the war. Peace will mean the de-mobilisation of not just combatants from active battle but also normalising the political space away from war propaganda.

There will be interests that will run counter to such a development.

The combination of these issues makes a timely resolution to the war crucial. The history of the world’s youngest state, neighbouring South Sudan, which has had a six-year civil war, should be instructive here. Many forget that a ceasefire had been agreed upon within just a year of that conflict, but it never amounted to anything meaningful as the war kept raging. To this day, two years after concluding a "comprehensive" peace agreement, the situation in the country threatens to devolve into outright civil war, mainly because of a lack of goodwill that persists between political forces. After so many years of war, it is not easy to unlearn the suspicion and cynicism that are characteristic of combat.

This is not to say that logical, rule-based and transparent processes should not be followed and that the process should be rushed. But bringing peace should also be treated with a sense of urgency to unburden a population traumatised by savage wars and suffering under siege. If the situation is left to fester for too long, and guns are not silenced with a peace deal, it could be a case of the tail wagging dog, where war drives the political agenda.

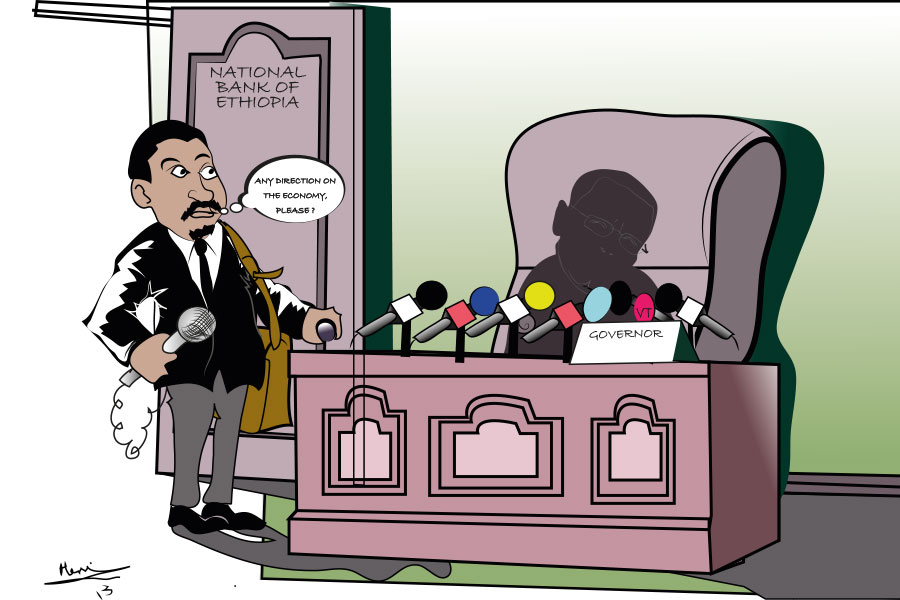

Accelerating a peace process will require recognising that the warring sides can have self-interests in ending the war. The international community could be highly consequential here. It needs to hone in on the fact that both sides have desperate needs for financing. Conflict-affected areas require massive rebuilding and rehabilitation programmes to return at least to their pre-war levels. At the same time, the federal government has a budget deficit mounting by the day, threatening the country with insolvency.

By drawing on the far and part but the existing commonality that inclines the warring sides to peace, the international community could play a positive role in helping the country return to relative peace. But the clock is ticking; there is no time to waste.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 09,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1145]

Editorial | Oct 30,2022

Fortune News | Jun 17,2023

Fortune News | Feb 10,2024

Editorial | Aug 21,2021

Fortune News | Jan 19,2024

Editorial | Apr 01,2023

Sunday with Eden | May 15,2021

Editorial | Feb 05,2022

Commentaries | Aug 08,2020

Fortune News | Oct 12,2019

My Opinion | 132151 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128561 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126482 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124091 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...