Feb 17 , 2024.

In the vast auditoriums of Addis Abeba, far from the era when flamboyant figures like Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi captivated the African Union (AU) stage, the continent's leaders convened last week in a more subdued assembly. The meeting, however, was not without its intrigues, notably marked by the presence of Somalia's President, Hassan S. Mohamud.

Despite a rhetorical skirmish with Ethiopia — a host country wrestling with its own set of controversies — President Mohamud's arrival was a statement in itself, framed by a pre-departure communique from Mogadishu. In it, he laid bare Somalia's staunch opposition to Ethiopia's naval base agreement with the self-proclaimed state of Somaliland, a move he deems a breach of the AU's foundational principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The gathering in Addis Abeba, though missing the larger-than-life personalities of yesteryears, was not devoid of significance. Beyond the political posturing and the inconvenience meted out to the city's residents, the summit's discussions hovered around themes of skill and education — a pressing concern for a continent where over 100 million children are out of school and no less than 34 million wander without parents or guardians.

Yet, the contrast of opulent dinners against the backdrop of Africa's deepening crises painted a grim picture of dissonance between the continent's leadership and the realities of its populace.

The African Union, conceived by the intellectual and political capital of leaders like Thabo Mbeki and Meles Zenawi; the pitiless pragmatism of those such as Paul Kagame; and the daring of others like Muammar Gaddafi, had promised a new dawn for a continent beset by historical injustices and developmental impediments. Tasked with cultivating peace, security, and economic integration, the AU aimed to usher in an era of prosperity that transcended the limitations and divisions of the post-colonial African states.

However, decades into its existence, the organisation stands at a confluence, beleaguered by the very issues it sought to eradicate.

The landscape of conflict in Africa, as detailed by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, remains a depressing reminder of the AU's utter failure to maintain the stability of the political order in member countries as well as safety and security to citizens. The continent, now eclipsing the Middle East in conflict-related fatalities, is a patchwork of unrest and perpetual violence, fueled by a mixture of state fragility, resource competition, and governance failures.

Despite the AU's institutional mechanisms for conflict detection and resolution, the proliferation of coups and insurrections in recent years evidenced a glaring disconnect between the organisation's ambitions and its on-the-ground absence. The disconnect extends into the economic realm, where the AU's vision of economic integration and prosperity is confronted by hurtful realities.

The global economic downturn, exacerbated by a contraction in Chinese lending — Africa's largest bilateral creditor until recently — has deepened the debt crisis for many African countries. The growing numbers of children living in extreme poverty and the escalating food insecurity crisis warn of a continent at the brink, struggling under the weight of international financial systems that seem increasingly unsympathetic to its plight.

Yet, it is perhaps in the domain of human rights and governance that the AU's inadequacies are most pronounced. Nearly four decades after adopting the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, the continent's human rights record remains dismal. The Human Freedom Index reveals a continent where the majority of countries languish at the bottom, a reminder of the AU's failure to uphold its charter's ideals.

The leadership of Moussa F. Mahamat at the Commission, criticised for complacency in the face of widespread violations, epitomises a broader institutional malaise — a body more preoccupied with bureaucratic posturing than with the tangible betterment of citizens' lives.

The AU's foundational premise was not merely the creation of a pan-African bureaucracy but the embodiment of a collective aspiration towards a future unshackled from the legacies of colonialism and strife. Yet, as the continent charts its ways in the 21st Century — marked by demographic shifts, environmental crises, and the persistent scourge of poverty and conflict — the AU's relevance and usefulness are increasingly and understandably in question.

The problem lies not in the scarcity of vision among Africa's leaders, past and present, but in their collective failure to translate this vision into tangible outcomes that resonate with the lives of ordinary Africans. The AU's struggle for relevance should be a manifestation of a broader crisis of leadership on the continent. The organisation's bureaucratic inertia, coupled with a lack of political will among its member states, has stymied its capacity to act decisively in the face of Africa's multifaceted troubles.

The proliferation of coups and the apparent public support for such undemocratic changes of government uncovers a deep-seated disillusionment with the status quo, where the AU is perceived not as a vehicle for transformation but as an extension of the very governance failures it seeks to overcome.

Last week's summit, focused on reforming the "international financial architecture", speaks to a recognition of the global dimensions of Africa's predicament. The debt crisis, a symptom of deeper structural imbalances in the global economic system, calls for a concerted effort to address the vulnerabilities of African economies. However, the AU's ability to advocate effectively for such reforms is hamstrung by its own internal weaknesses and the divergent priorities of its member states.

The vision of a prosperous, united Africa, championed by the continent's post-independence leaders, remains an elusive goal. As the AU struggles with the legacy of its ambitious but unfulfilled mandates, the need for reinvigorated leadership is clear. The leadership must not only embody the idealism of the organisation's founding fathers but also possess the pragmatism and resolve to address the pressing problems of the present.

The path forward for the AU and for Africa as a whole lies in bridging the gap between lofty aspirations and the concrete realities of governance, development, and human rights. The Union's leadership is faced with the task of redefining its role in a rapidly changing continent. The tasks are daunting, but they should not be viewed as insurmountable. With renewed commitment and a pragmatic approach, a team of new leadership at the Commission can have the potential to play a defining role in shaping the future of Africa.

However, this requires a departure from business as usual — a shift from a focus on bureaucratic processes to a results-oriented approach that prioritises the welfare of African citisens and not of the states. As the continent confronts a perfect storm of demographic, environmental, and economic clouds, the AU's ability to adapt and evolve will be the true measure of its relevance and effectiveness in the years to come.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 17,2024 [ VOL

24 , NO

1242]

Editorial | Feb 05,2022

Editorial | Feb 22,2020

Viewpoints | Mar 16,2019

My Opinion | Jul 19,2025

Agenda | Aug 04,2024

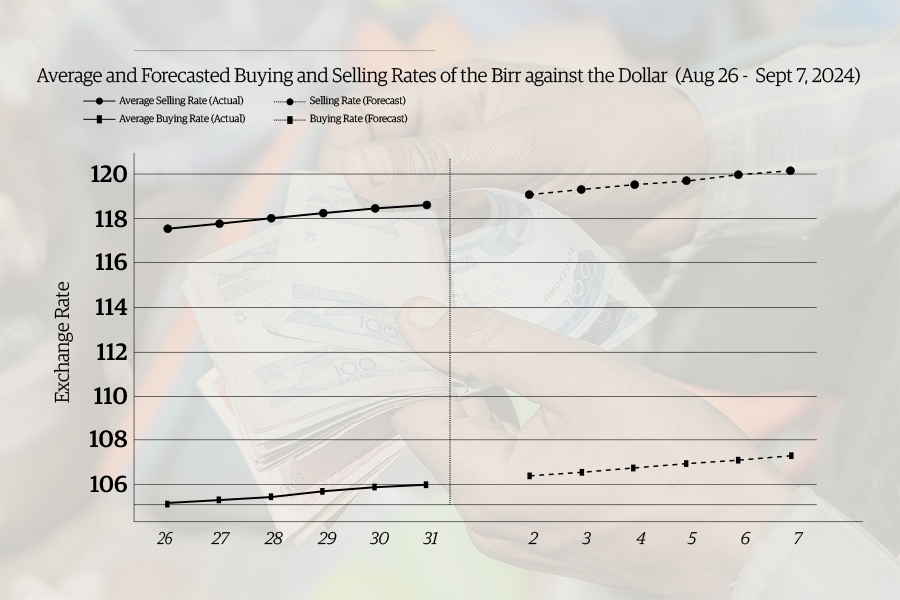

Money Market Watch | Sep 01,2024

Editorial | Aug 03,2024

Fortune News | Apr 13,2019

Editorial | Oct 01,2022

Editorial | Sep 06,2020

Photo Gallery | 174521 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164748 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 154930 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136686 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...