Fortune News | Oct 24,2020

Jan 4 , 2020.

The announcement came without much fanfare. But Jawar Mohammed’s decision to join the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFCo), chaired by Merara Gudina (Prof.), was the most significant political news of the past few months.

The most consequential political personality of his generation, Jawar's next move has been a subject of speculation ever since his return from the United States. Nonetheless, it remains fuzzy under what conditions he will join, for he is still a non-Ethiopian citizen, which the recently legislated electoral law does not permit.

Regardless, one thing can be certain. If observers had complained that election campaigning, at least in the declarations of manifestos, was behind schedule, it seems that organised groups with political agendas are making up for time now.

Coming on the heels of the merger of the EPRDF into the Prosperity Party (PP), the prominent activist’s move testifies to a slowly building momentum for electoral campaigning in the race to win seats in federal and regional legislative houses in the coming national elections. With the diaspora community most likely to wet the beaks of several major opposition parties, the meteoric rise of the influence of social media and the unprecedented surge in political awareness among the youth, the coming elections will make the one in 2005 look like child’s play in terms of historical significance.

The coming few months will likely be brimming with coalitions, mergers and campaign trails, if not more. The National Electoral Board is gearing up preparations, and the attention of the international community has been focused on Ethiopia, perhaps increasingly with worries. The inclusion of Ethiopia in the Crisis Group’s top 10 conflicts to watch across the world in the new year is mainly a result of the contestations for power in a political space where there is a great deal at stake.

There is good and bad news here.

The good news is how organised groups have become willing, at least on the surface, to transfer contestations from the streets to institutional and legal settings. The act displays a level of trust groups and opposition parties have come to place on the institutions of the state, however inexplicit this trust may be. It is a big win for a state that almost always had several political forces advocating its violent overthrow.

The bad news is that elections in countries with weak democratic institutions are rarely peaceful. A study carried out by the University of Johannesburg last year found out that in the six years from 2011, where over 100 general and municipal elections as well as referenda took place in 44 countries across Africa, almost all of them saw violence at one stage or another. Violence during elections has risen hand-in-hand with the start of multi-party democracy on the African continent.

The more power and resources have been concentrated at the centre, the larger the stakes are. It is more likely that contenders for political offices would go outside of the bounds of the institutional and legal settings to come out as the victor. Under such an environment, inflammatory rhetoric, intimidation and violence take centre stage.

What would follow is the “violent unraveling” the Crisis Group warns unless critical steps are taken to address the challenges highly contented elections would bring. Fortunately, all this would require is not outside the reaches of the political players and the democratic institutions entrusted to oversee elections credibly take place in the eyes of the electorate.

There are elements of this the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) has tried to address. The elections of credible individuals to the Supreme Court and the Electoral Board is not something to baulk at. The code of conduct signed by over 108 political parties to set rules and guidelines for their activities was also no easy task. These were positive steps that were able to bring a level of trust to institutions and set certain accepted guidelines for the actions of organised groups across the country.

But the complicated political forces at play in Ethiopia are close to rendering these achievements null and void. Both the Supreme Court and the Electoral Board have had their controversies over the past several months. The forces of political expediency have overshadowed the goodwill that had been established at the signing of the code of conduct.

The consequence of these challenges is a lack of redlines for a peaceful, legal and institutional political contest to take place. The general euphoria felt by the public and endorsed by political elites in April 2018 when Abiy came to office has decidedly ended.

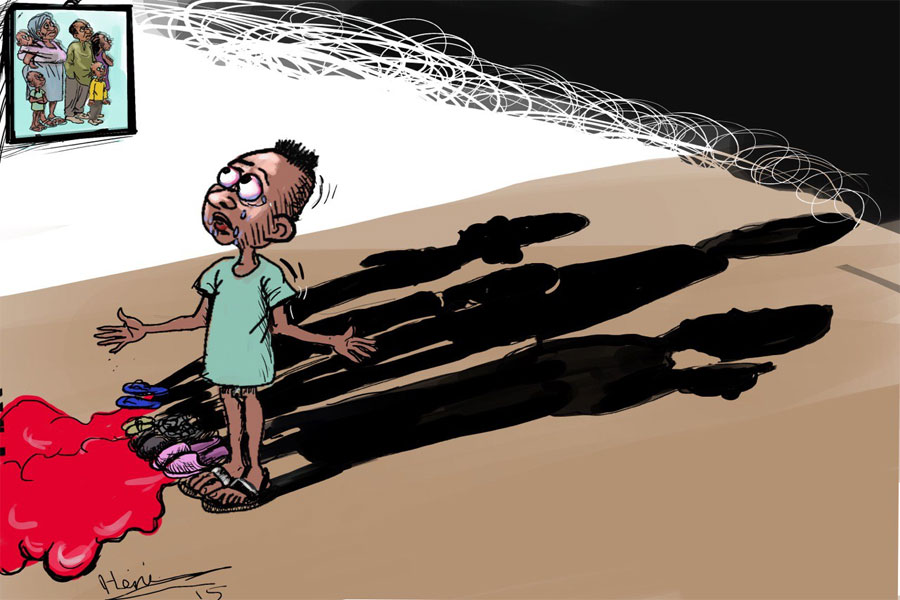

The gloves are now off. Rhetoric between political players have escalated, while their supporters have resorted to violence to intimidate one another. Worse, political debates have devolved into shouting matches. Hot-button political issues, matters that could be discussed and compromised on, have become a rarity. They are now used as tools from where they dig deep trenches and fire inflammatory rhetoric. Each is so far from one another, all they hear is their own gunshots.

There is no consensus and shared vision on what sort of Ethiopian state leaders of various political parties would want to see sustained or reconstructed.

The debate around federalism is the best example to show the breakdown in communications. All sides in the political divides are entrenched deeply in their own beliefs that they swear that their opposition is out to bring doom and darkness to the country. They refuse to explain their positions without resorting to the use of fearmongering, ad hominem attacks or ridicule.

While it is only natural that ideological differences are becoming starker as electoral politics dominate the playing field, the bullish rejections of opposing ideas is leading to further radicalisation. Most political issues, in dire need of sober analysis and reflection, are being approached with such venom and a sense of antagonism they have become pointless to talk about.

It is thus impossible to move forward unless redlines are identified. It can start by upholding the guidelines laid down in the code of conduct the opposition parties have agreed to. Every political contest should only take place under the legal and institutional means, and violence can never be considered a legitimate way of currying votes at the polls. The political players can go one step further and recognise the need to hold sober discussions over any issue of consequence.

Debates devoid of logic and overflowing with emotions might as well not be had.

Even more crucial would be the task ahead for constitutional institutions to maintain impartiality in the face of heated political contestations. Their test would come in their professional discipline, the precedents they set and their understanding of the subtleties of politics in Ethiopia. The institutions' trustworthiness would also be seen in the courage in their conviction to call a spade a spade and deal with abuses to the law by political parties according to the constitutional and legal guidelines.

If this fails to be the case, elections in themselves will not necessarily prove to be fair or peaceful, let alone credible.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 04,2020 [ VOL

20 , NO

1027]

Fortune News | Oct 24,2020

Fortune News | Jan 11,2020

Fortune News | Dec 10,2018

Radar | Oct 09,2021

Verbatim | Oct 20,2024

Fortune News | Nov 04,2020

Fortune News | Mar 04,2023

Editorial | Dec 10,2022

Radar | May 25,2019

Editorial | Feb 01,2019

My Opinion | 131970 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128359 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126297 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123912 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...