Commentaries | Nov 29,2020

Mar 21 , 2020

By Dejen Yemane

Ethiopia’s late prime minister, Meles Zenawi, is controversial on various fronts. Many denounce him for introducing federalism along lingo-cultural lines, which they say has contributed to socio-political division and the disintegration of national unity.

Many of his critics are also not impressed with his style of rule and conduct of power that has resulted in one-party hegemony, democratic centralisim that overflowed into government and the authoritarianism of the state. On the other hand, many take him as a symbol and guardian of diversity and multi-ethnic federalism.

Sentiments against or in favour of his political ideology and legacies may still persist for years to come. One of these that will continue to be discussed is his success, or lack thereof, in protecting Ethiopia's national interest. For this, the Assab sea-outlet and Blue Nile River are the litmus tests for Meles’s positions in this regard.

It was following an arguably unfair referendum that Eritrea seceded, and Ethiopia’s transitional government was the first to give it recognition. But a proper state succession among the predecessor and successor states did not take place. There was no devolution agreement between the two countries to regulate property division and the transfer of rights and duties due to the treaties entered by Ethiopia when Eritrea was a part of it.

Subsequent relationships were managed informally, through the personalities and major parties of the two countries, especially the TPLF and the EPLF (People’s Front for Democracy & Justice after 1991), two leftist rebel liberation movements that were the major factors in toppling the Dergue.

The honeymoon period, however, was short-lived as tensions were kindled among the then leaders of the two countries. The implicit cause for the pressure was, arguably, the struggle for hegemony in the region. It was the fight between the parties at the helm of both countries’ governments that steered toward that devastating war. On the surface, though, a border dispute was given as a reason, and Eritrea’s invasion of Badme, an immediate cause of it.

The war, which was concluded by Ethiopia’s victory, later became a diplomatic and legal battle. This decision is indeed remembered as an ignominious one to give back the victory to the defeated state in the eyes of many Ethiopians. It was the Algiers Agreement signed between the then leaders of the two states that mandated The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) to arbitrate the border issue and the claims of the two countries.

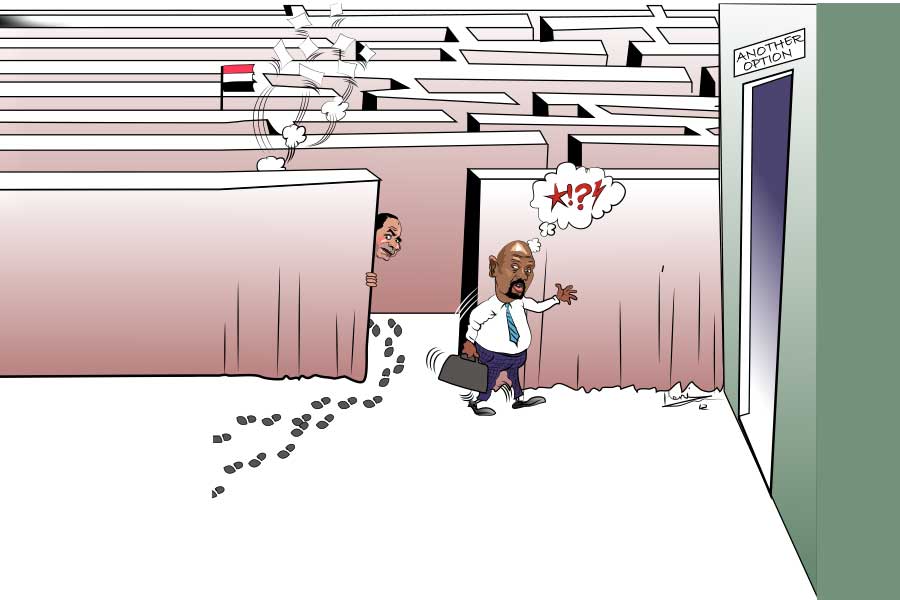

The arbitration process was done against the national interest of Ethiopia, from its start to completion. One major reason for this was that the Assab sea-outlet was not the subject of the arbitration, despite the public concerns and requests from scholars like Yakob Hailemariam (PhD).

International law, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, state that “Land-locked States shall have the right of access to and from the sea for the purpose of exercising the rights provided for … including those relating to the freedom of the high seas and the common heritage of [humankind].”

Ethiopia would have had the basis to ask for the right to access the port. Perhaps, it was for the best this issue was not made a part of the litigation at The Hague. The issue is not closed, and Ethiopia could at any time bring up its right to make use of the Assab port based on international law.

Besides a refusal to litigate the Assab port, Meles responded to the public concerns as “let them water their camels with it.”

As far as the EPRDFites under Meles were concerned, this was a dereliction of duty when it came to the national interest.

This is in contrast to Meles’ track-record on what is now a hot topic - the Nile River. Meles’s administration played the role of custodian toward the country that produces at least four-fifths of it. The world remembers him for his historical measure to launch the multi-billion-dollar Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam(GERD), initially called the Millennium Dam, on the Blue Nile.

Before the commencement of the project, Meles had been striking deals and making agreements to smooth over the waters for what was likely going to become a greatly controversial project. He approached downstream countries, who have exclusively appropriated the Nile waters through a 1959 bilateral agreement, to reverse their hegemonic understanding toward a more democratic utilisation of the Nile waters.

To that end, Meles first approached Sudan’s leaders and signed the Ethiopia-Sudan Peace & Friendship Agreement on December 23, 1991. In this agreement, both states recognised the common ownership of the Nile River among the co-basin states. They have affirmed equitable entitlements to the uses of the Nile waters without causing significant harm to one another. They have also acknowledged Ethiopia’s absence from previous initiatives and agreements on the Nile. Ethiopia’s determination to full-scale participation in the Nile issues in the future is also professed in the agreement. Sudan accepted Ethiopia’s equal right to use of the Nile waters, despite the 1959 water appropriation agreement between Egypt and Sudan.

Two years later, Ethiopia approached Egypt to bring the latter into agreement on the equitable use of the Nile waters. Ethiopia and Egypt concluded a framework for regional cooperation on July 1, 1993. The agreement was signed by Meles Zenawi and Hosni Mubarak. In this agreement, the states agreed to use the Nile waters on the basis of the rules and principles of international law and to refrain from causing significant harm against the co-basin states while utilising the Nile waters.

It was also during Meles’s administration that the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) and the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFI) were negotiated and adopted to utilise the Nile River on the basis of cooperation. These two are pioneers in designing a comprehensive plan for the Nile waters based on cooperation and equitable means.

Meles has a precarious legacy when it comes to the national interest and studying these two fundamental issues should offer an insightful reflection on the performance of the EPRDF in its 27 years in power.

Meles made a noticeable impact in countering downstream’s countries monopolistic utilisation of the Nile waters, while he failed to secure Ethiopia’s right to the use of the Assab port against the present and the future generation of the country.

Arguably, Meles tried to offset his disastrous decision committed in the early stages of leadership against the national interest by playing a brave custodian role on the Nile River in his later years in office. We should recognise his role over the Nile River, while we litigate right of access to the Assab port. Our fight over either of the two national interests is not yet over.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 21,2020 [ VOL

20 , NO

1038]

Commentaries | Nov 29,2020

Editorial | Jun 20,2020

Commentaries | Feb 06,2021

Commentaries | Nov 09,2024

Commentaries | Feb 08,2020

Viewpoints | Dec 04,2020

Commentaries | Jun 13,2020

Commentaries | Apr 10,2021

Viewpoints | Jan 16,2021

Radar | Nov 11,2023

My Opinion | 131584 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127940 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125915 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123539 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...