Addis Fortune Press Release | Oct 04,2024

Dec 7 , 2024.

For decades the Ethiopian Petroleum Supply Enterprise (EPSE), a state-owned giant entrusted with importing and distributing fuel, dominated the energy sector. It administered 13 reserve depots spread across the country, maintaining emergency stocks to cushion against disruptions caused by natural or artificial calamities. However, its ambitions were considerable.

Last fiscal year, it planned to import 760,000tn of benzene and 1.2 million tons of diesel, though it managed only to accomplish about 72pc of the goal. Such shortfalls may not be unheard of in global markets prone to volatility and logistical strains. Yet, the Enterprise’s latest audit report presents a far more unsettling picture than a few missed targets would imply. Such shortfalls may not be unheard of in global markets prone to volatility and logistical strains. Yet, the Enterprise’s latest audit report presents a far more unsettling picture than a few missed targets would imply.

On the surface, the Enterprise recorded a revenue surge in 2023, exceeding 25pc over the previous year, which might have suggested growing strength. Yet beneath this top-line buoyancy lurked grim realities. The cost of sales swallowed 99.6pc of revenue, leaving margins razor-thin. Its net profit collapsed, provisions for bad loans soared, and once-reliable liquidity buffers drained away. Over half of its deposits vanished in a year, raising uneasy questions about the Enterprise’s underlying stability.

The country's flagship petroleum supplier has run into the turbulent forces of global price swings, fragile supply chains, and escalating credit risks tied to customers who fail to settle their bills on time.

If the Enterprise cannot withstand these financial headwinds, the repercussions could spread into sectors ill-prepared for disruptions. Rising prices at the pump might strain households and businesses, while stiffer credit terms could stifle expansion in industries counting on steady and reasonably priced fuel.

Understandably, no government can blithely ignore such vulnerabilities.

According to the Minister of Trade & Regional Integration (MoTRI), Kassahun Gofe (PhD), who recently addressed federal legislators, the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) is considering a shift in policy. It has reviewed a bill on the fuel trade system that would allow private companies to enter the market alongside the Enterprise. The logic is beguilingly simple. Competition might bring efficiency, attract foreign investment, and improve procurement, infrastructure, and distribution, ultimately resulting in fewer shortages and perhaps fairer prices for consumers.

Displacing a state-run monopoly with multiple players could, at least in theory, unlock competition and reduce the chronic inefficiencies that have long plagued the system for decades. Yet liberalisation is rarely a straightforward affair.

The apprehension that private operators, driven by profit, would focus on lucrative urban markets, neglect rural areas, and reinforce inequality is worthy of sufficient consideration. Price volatility, already endemic in global oil markets, might grow more pronounced without the efficient regulatory hand of the state. Private investors could hoard supplies or manipulate the market to drive up prices, opening the gates to competition without robust safeguards. This could be simply trading one set of problems for another.

However, this debate is hardly unique to Ethiopia.

Other African countries have experimented with similar reforms, hoping to transform inefficient, state-dominated oil markets into more dynamic environments.

Consider Kenya, where dismantling price controls and encouraging competition in the early 2000s yielded some successes. Market concentration eased, and private investment in import infrastructure grew. Yet, the anticipated dividend from retail distribution remained elusive. Oligopolistic practices endured, and new entrants struggled to claim more than a token share.

Kenya offers a good lesson for Ethiopia's legislators and policymakers that liberalisation of the fuel sector, while capable of shaking up old orders, may not alone guarantee a truly level playing field.

Examples from Mali and Uganda illustrate the perils of liberalising without adequate regulatory frameworks. Uganda’s fully liberalised market failed to deliver the promised efficiency gains or cost reductions. Instead, distribution margins and retail prices rose, and major oil marketing firms tightened their grip.

Mali’s initial embrace of liberalisation was no less chaotic. In a “wild west” atmosphere of lax regulation, tax evasion and environmental hazards thrived, corroding trust and undermining any potential gains. Later reforms tried to rein in excesses, but repairing the damage proved difficult.

Ghana took a more measured approach, retaining a degree of state intervention while selectively embracing liberalisation. The hybrid strategy delivered relatively low inland distribution margins and established a more equitable infrastructure network. Nonetheless, as has been the case with Ethiopia, state-owned entities absorbed hefty public funds, casting doubt on the fiscal sustainability of a model that tried to have it both ways.

Ghana’s caution prevented chaos but also risked entrenching inefficiencies that reforms are meant to root out.

What emerges from these varied African experiences is a consistent lesson about sequencing and institutional readiness. Successful liberalisation demands more than deregulating prices and inviting private entrants to do as they please. It requires building modern petroleum laws, dismantling distortive subsidies, and ensuring regulators have the teeth and competence, if not the discipline, to keep the market honest.

Kenya’s relatively modest success can be attributed, at least in part, to a more disciplined approach to implementing reforms. Uganda’s hands-off approach, by contrast, gave opportunistic players far too much latitude.

Price deregulation, so often the centrepiece of such reforms, represents the crux of the problem. In theory, freeing prices from state control encourages efficiency and draws private capital. In reality, much depends on the market structure that emerges. If a handful of players dominate, deregulation may transfer the state’s former pricing power into private hands, leaving consumers no better off.

In many cases, consumers, the intended beneficiaries of liberalisation, have found themselves paying more.

Geography complicates matters further. For landlocked countries dependent on neighbours’ transit routes and infrastructure, petroleum market reforms can be undermined by regional conditions. Kenya’s partial successes are entwined with its role as a supply hub for Uganda. Ethiopia may find its reforms influenced, for better or worse, by the policies of Djibouti, its outlet to the sea. Coordinating across borders might be needed to ensure that liberalisation does not bring unintended shocks to countries relying on external supply chains.

At the heart of all this lies a profound question about the balance between the state and the market. Liberalising a sector from state control might seem tempting, yet market failures, exploitation, and inequality are no less real concerns than bureaucratic inertia and inefficiency. As Ghana’s example showed, the most effective models find a middle path. Effective regulation can coexist with healthy competition, allowing private ingenuity to thrive while preventing excesses.

However, achieving such equilibrium will be no easy feat. Without strong oversight, liberalisation can quickly morph into a source of instability, leaving vulnerable consumers stranded. Without some measure of competition, state monopolies grow complacent and unresponsive as vehicle owners are subjected to queues and wasteful times before gas stations in Addis Abeba.

Ethiopia’s policymakers, then, face a delicate task. The rewards of introducing private players could be substantial. It is more efficient procurement, improved infrastructure, reduced shortages, and even fairer prices. But letting go entirely would be reckless of them. The federal government should preserve a firm regulatory role to ensure rural areas are not neglected, to stabilise prices in times of turmoil, and to prevent opportunistic hoarding.

For now, the jury is out. Ethiopia has reached a juncture where its flagship petroleum supplier’s struggles have raised the spectre of deeper structural problems as the disabling shortages in Sidama Regional State uncovered. The ideal scenario would encourage private investment and competition while ensuring consumers, especially in poorer or remote areas, do not suffer from neglect or rising retail prices. That will require careful planning and regulatory vigilance.

Like any country, Ethiopia needs secure, stable, and reasonably priced energy sector. If its leaders choose their policy path wisely, market forces can help them reach that goal. Otherwise, they risk running the country and its people's hopes on fumes.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 07,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1284]

Addis Fortune Press Release | Oct 04,2024

Fortune News | Jun 22,2024

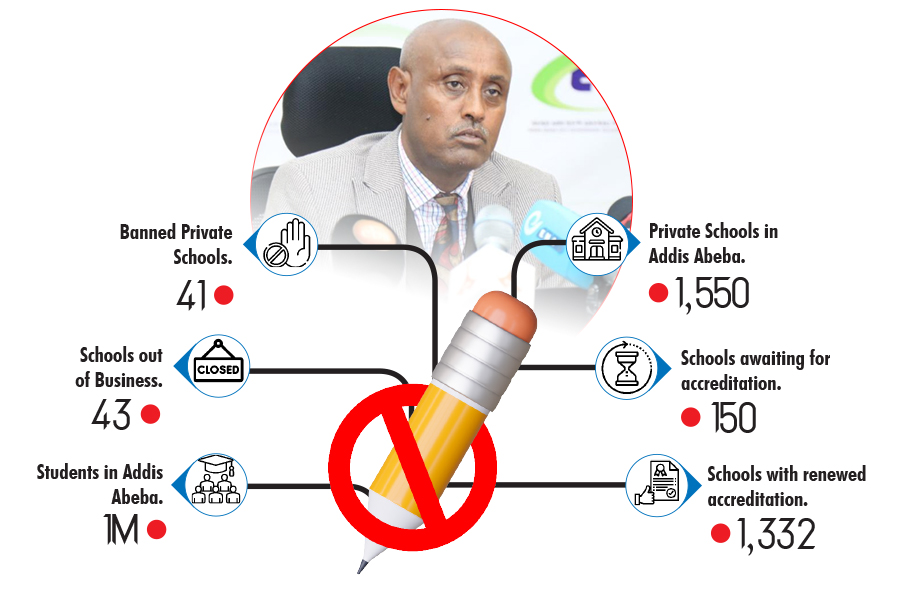

In-Picture | Oct 27,2024

Commentaries | Dec 25,2018

Fortune News | Aug 14,2021

Radar | Jul 02,2022

Agenda | Mar 20,2021

Featured | Sep 18,2021

Commentaries | Jul 03,2021

Fortune News | Nov 30,2019

Photo Gallery | 149652 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 139941 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 134699 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 131270 Views | Aug 21,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

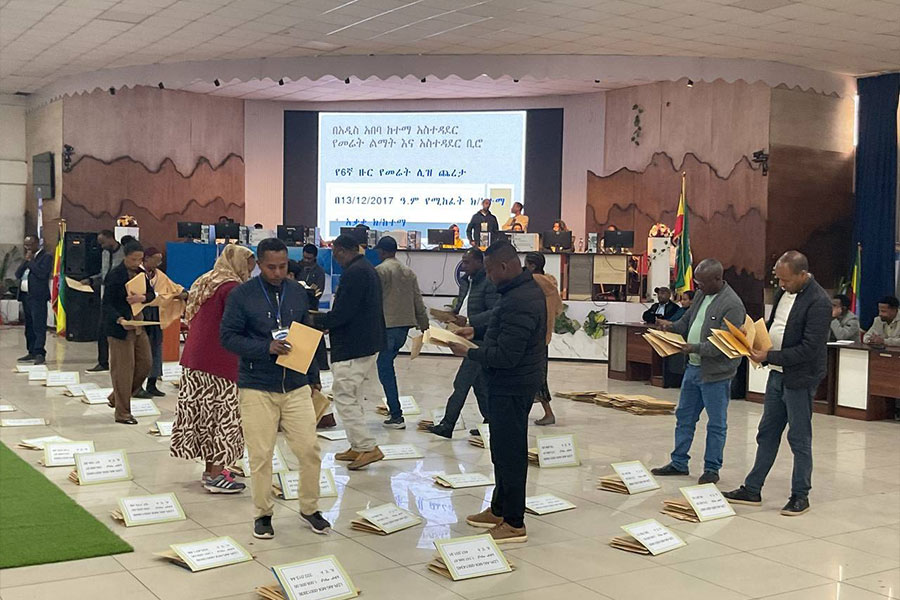

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Addis Abeba's sixth public land lease auctions after a five-year pause delivered mixe...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Brook Taye (PhD), the chief executive of the Ethiopian Investment Holdings (EIH), is...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

For decades, Shemiz Tera in the Addis Ketema District of Atena tera has been a thrivi...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A dream of affordable homeownership has dissolved into a courtroom showdown for hundr...