Editorial | Jun 12,2021

Jul 13 , 2024

By Celestin Monga

After years in the economic doghouse, industrial policy is back and making a splash. The IMF recently hosted a star-studded conference spotlighting this shift, drawing in top economists to discuss why governments from the US to South Africa are rolling out new industrial strategies. In this commentary provided by Project Syndicate (PS), Celestin Monga, who teaches public policy and economics at Harvard Kennedy School, argues that the fear of deglobalisation, supply-chain hiccups, and trade wars have driven this policy renaissance.

After decades of disparagement and disdain, industrial policy is back on the global economic agenda. Perhaps the strongest evidence of this rehabilitation is a recent international conference on rethinking structural transformation, cosponsored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and attended by some of the world's most influential economists.

Industrial policy is back in vogue for many reasons, including fears of deglobalisation, the emergence of a multipolar world, supply-chain disruptions, the return of economic nationalism, and trade tensions (most notably between the United States and China, but also among Western countries). Governments in the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), France, Vietnam, Brazil and South Africa have all issued industrial-policy blueprints.

But, despite renewed global interest in industrial policy, intellectual and policy elites remain confused about its precise meaning, specific instruments, and how it differs from other economic policies. This is true of economists who advocate it, as well as those who disparage it.

In a famous 1791 report, the first US Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, framed industrial policy as government measures to boost manufacturing and so-called "productive" sectors. That definition has evolved and expanded over the past two centuries to reflect economic transformations and the need to think beyond manufacturing.

The term now encompasses all government interventions – from subsidies and tax incentives to public procurement and the design of intellectual property protection – "that explicitly target the transformation of the structure of economic activity in pursuit of some public goal." By that measure, industrial policies are those that are designated as selective and intentional. But, these labels remain random, and focusing on policymakers' stated intentions is risky.

Would anyone use public proclamations by politicians to measure democratic governments' policies?

Recent IMF research has gone a step further, distinguishing between "vertical" industrial policy favouring specific sectors – putatively a source of market distortions, state capture, and rent-seeking opportunities – and "horizontal" economic policy focused on improving the business environment for all industries and firms. The horizontal approach is deemed fair, and even desirable.

But, this new conventional wisdom reflects a misleading consensus on the proper scope of government intervention. Perhaps more importantly, the distinction between industrial and economic policy is fundamentally false. Drawing a line between "good" ("horizontal" and "neutral") and "bad" ("vertical" and "targeted") government intervention may be politically attractive, but does not hold water either conceptually or in practice.

Almost all items in a national budget could be classified as industrial policy because they implicitly or explicitly favour particular places, sectors, or businesses. The decision to build any productive infrastructure in a specific location always provides (unfair) advantages to certain regions or firms.

The macro-financial policies often presented as the antithesis of industrial policy are, in fact, not wholly neutral. For example, exchange-rate measures favour some sectors and industries more than others. Likewise, financial-sector regulation, often portrayed as the most "neutral" and "horizontal" government policy, shapes an economy's sectoral allocation.

The benefits that accrue to some industries and firms are not always obvious. The US banking industry is a case in point: the Federal Reserve (a branch of the government) lends money to banks at an interest rate of one percent, which the banks then use to buy Treasury bills (from the same government), yielding roughly four percent. This represents about 30 billion dollars in annual subsidies, more than any developing country would ever grant to one industry.

Social safety nets to mitigate poverty and progressive income taxes to reduce inequality also affect the economic structure, because they imply winners and losers, often in specific geographic areas or social groups. The World Bank's public expenditure reviews and benefit-incidence analyses often capture important distributional issues about who benefits from this type of spending.

On a more fundamental level, policies always have indirect effects. For example, in countries with limited fiscal space, well-meaning social programs presented as neutral cross-cutting projects – not intended to favour particular industries or regions – can still change the economy's structure if they cause public-debt levels to rise and pose risks to financial stability, which would disproportionately harm certain sectors and groups.

Given this, it is delusional to think that the effects of "vertical" industrial policy can be detached from those of broad macroeconomic or regulatory policies and studied in isolation. Both types of policies always have economy-wide repercussions, whether direct and observable effects on other sectors or industries, or indirect opportunity costs for various economic agents.

Attempts to disentangle these outcomes will almost always result in noise, not signal. Empirical studies using tariffs and quotas to assess the effectiveness of industrial policy in any given country often fail to consider that such measures help generate additional fiscal revenue, achieve terms-of-trade gains, and protect non-competitive or infant domestic industries.

Almost all economic policies aim to improve the economy's structure or achieve a social goal and require the use of instruments that will directly or indirectly favour some industries, sectors, or firms. The controversy over industrial policy is largely a matter of semantics: governments implement these banal strategies of economic transformation on a daily basis.

Just as Monsieur Jourdain in Moliere's "The Bourgeois Gentleman" discovers that he has been speaking prose all his life without realising it, economists should finally acknowledge that almost all economic policy is, in fact, industrial policy. The question, then, is not whether to use it, but rather how to do so transparently and well.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 13,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1263]

Editorial | Jun 12,2021

Radar | Aug 21,2021

Fortune News | Nov 03,2024

News Analysis | Dec 09,2023

Radar | Feb 05,2022

Commentaries | Sep 10,2022

Commentaries | Mar 02,2019

Commentaries | Sep 10,2022

Viewpoints | Aug 03,2024

Commentaries | Apr 13, 2025

Photo Gallery | 155312 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 145589 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 135172 Views | Aug 14,2021

Photo Gallery | 134081 Views | Oct 06,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

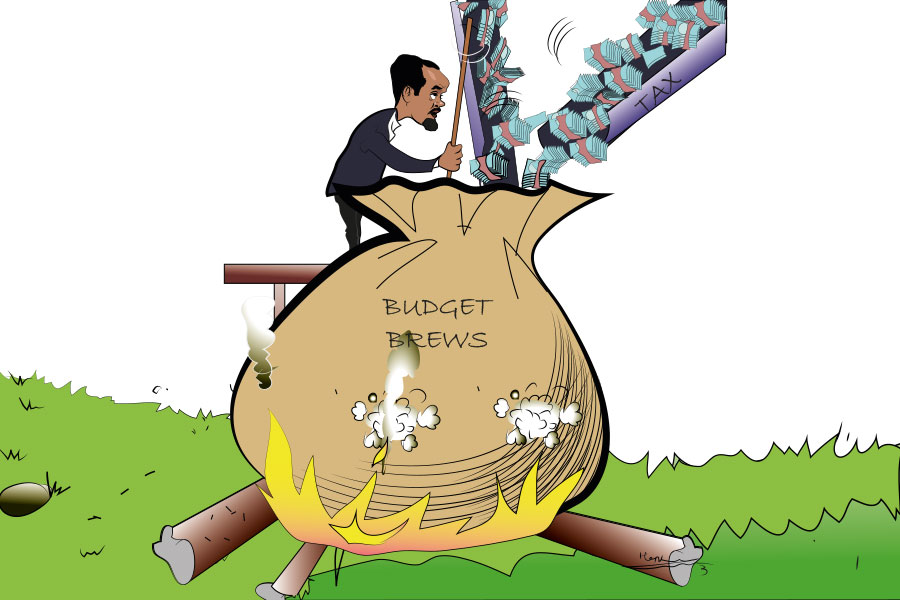

Sep 15 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric power proj...

Sep 13 , 2025

The initial budget in 2011 was 80 billion Br, but this figure swelled to a revised cost of 240 billion Br by 2024, a challenge that was exac...

Sep 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Banks are facing growing pressure to make sustainability central to their operations as regulators and in...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Cabinet has enacted a landmark reform to its long-contentious setback regulations, a...