Radar | Jul 06,2025

Aug 18 , 2024

By Tsedeke Y. Woldu

Liberalising the forex market marks a significant step towards ending financial repression in Ethiopia. If successful, this bold move could open up unprecedented economic opportunities. However, the risks are enormous and must be managed with great care. Fortunately, the IMF document outlining the management procedures has identified, quantified, and described these risks. Whether Ethiopia is ready to face these challenges remains to be seen, writes Tsedeke Yihunie, Flintstone Engineering & Homes S.C. founding shareholder.

In June 2019, a few days before the deadly coup in Bahir Dar, I found myself locked in a heated argument with a high-ranking official from the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). I had completed my first book, a fresh copy in hand, and was proudly swaggering that I had devoted 200 pages to criticising the central bank's stifling financial repression. The official, who is no longer with the NBE, responded with calm authority, suggesting that I was out of my intellectual depth and that there is no such thing as repression (“anti-democratic” was the term we used) in financial economics.

At the time, I was fervently passionate about the momentum of the ongoing democratic reforms. I was indignant that he would not acknowledge that true democratic change should begin by overhauling the central bank's repressive financial policies.

Despite my focus on financing the now obsolete Growth & Transformation Plan (GTP), my thoughts on the forex regime were clear. I argued for eliminating financial repression, particularly defending the right to trade or own foreign assets. I also advocated for reforming NBE governance, ensuring its leadership was independent yet accountable, engaging in market operations to stabilise the forex market, and capping foreign reserves to maintain market efficiency.

I also proposed that the Birr should either float freely or be pegged hard to the dollar when reserves were sufficient.

Fast forward to July 29, 2024.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a 3.4 billion dollar Extended Credit Facility (ECF) for Ethiopia, with an immediate disbursement of one billion dollars. This arrangement, dubbed the “Addis Ababa-Washington Consensus” by a columnist at "Ethiopia Insight", marked the culmination of a series of financial liberalisation reforms that had begun in December of the previous year. The most consequential of these reforms was the free-floating of the Birr, an unprecedented move that took the public and the banking sector by surprise.

While some had expected a substantial devaluation of the Birr, the reality of a fully liberalised forex market caught many off guard. Economists on the left decried the move, seeing it as the end of pro-poor policies in Ethiopia. However, for those who had long advocated for a free Birr, it was a moment of celebration — though with some reservations.

Capital controls remained in place, multiple currency prices (MCP) had been (temporarily) allowed, and legacy debts, particularly from fuel imports, were likely to absorb any early disbursements from the IMF. Neither the NBE nor the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), and certainly not the private banks — suspected of opposing the reforms — seemed ready for a fully liberalised forex market or treasury bill (T-bill) market.

What really happened?

To understand the situation, one should delve into the 144-page document accompanying the IMF’s press release. This document, rich in quantitative and qualitative analyses, offers a comprehensive view of Ethiopia’s economic condition domestically and globally. It outlines the key elements of the reform, detailing what has been accomplished, what is in progress, and what is planned. The annexes reveal what the Ethiopian authorities requested, the policy concessions made, the terms of the credit facility, and the technical memorandum of understanding between the Ethiopian government and the IMF.

They also unveil the World Bank's obligations and expectations from other development partners, including international creditors. Notably, France and China co-chaired the discussions on contributions from these partners, ensuring that all major players were aligned with the reforms and committed to the initiative's success.

The most critical parts of the IMF document are the performance criteria and indicative targets by which the proper utilisation of the credit facility and the effectiveness of the reforms will be monitored. These criteria, along with detailed requirements for periodic reports on financial and real-sector markets, shed light on the true nature of the changes implemented on July 29, 2024. By floating the Birr, the NBE seeks to make the currency freely convertible, a momentous step towards ending financial repression in Ethiopia.

However, this move brings with it considerable risks that should be managed carefully.

Price and currency instability are well-known enemies of trade. Price instability, often in the form of inflation, creates an erratic price differential between producers and consumers, wreaking havoc on business decisions. In financial environments where central banks control inflation through money supply restrictions and trade controls, the actual cost of capital becomes unpredictable, leading to inadequate working capital, ephemeral pricing decisions, and contract defaults.

The result is often soaring unemployment. Similarly, currency instability, particularly when the local currency is overvalued, disrupts external trade by distorting exchange rates. This distortion, caused by government intervention, restrictive policies, balance of payment shortfalls, or inflation differentials, undermines confidence in the local currency, further destabilising trade.

The attempt to make the Birr a convertible currency is an effort to respond to these trade obstacles. Currency conversion through liberalisation is a contentious issue, but there is little dispute that the Birr has been misaligned from its true value for much of the last five decades. It is about time this misalignment was corrected.

However, simply allowing the Birr to float freely against the world’s major currencies will not make it fully convertible overnight. Nor will the various laws and directives enacted by the Ethiopian government at the urging of the IMF and its partners. But, coordinated implementation of these rules and regulations might achieve this goal.

Crucial to this effort is balancing the budget paying for deficits with market interest rates and fighting inflation through interest-based monetary policy and government bond market operations. It should also incorporate restructuring domestic and international debt and address the inefficiencies of state-owned enterprises, notably those heavily indebted and reliant on subsidies, such as the Sugar Corporation, the Ethiopian Railway Corporation, and the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation. These and other regulations to address fiscal, prudential, and social risks have been rapidly pushed through the implementation process.

The IMF document emphasises performance criteria related to fiscal risks, particularly in measuring and financing budget deficits. Prudential risks for commercial banks, the most impactful directive, may not be the limits on exposure to single borrowers or related parties, but rather the restrictions on the frequency of loan restructuring when in distress. A regulation lowering the threshold for non-performing loans to 20pc of a borrower’s portfolio could also prove effective in containing risk, though it may come at the expense of borrowers’ liquidity.

Despite the end of financial repression, the government’s focus on social risks remains.

The long-standing subsidies on essential goods like fuel, wheat, medicine, edible oil, fertiliser, and sugar will continue. While underpricing of utilities, particularly electricity, may not last as long, it will persist in the early stages of the program. The continuation of the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP), with a fiscal outlay of 0.4pc of GDP, has been secured, ensuring support for the most vulnerable populations.

Subsidies and safety nets will cost the government 1.4pc of GDP, or about 20pc of revenue, a burden financed mainly by donors, particularly the World Bank. The Ethiopian Petroleum Supply Enterprise (EPSE) and its stabilisation fund will remain active until subsidies are fully phased out by the end of the ECF’s tenure. This strong commitment to pro-poor spending, where government contributions to the productive safety net program are expected to quadruple from 0.1pc to 0.4pc of GDP, likely contributed to the “Addis” prefix in the “Washington Consensus.”

However, with all the references to GDP — mentioned 307 times in the IMF document — one must question how accurately Ethiopia’s GDP can be estimated. Given that the latest census data will be more than 20 years old by the end of the IMF program, the efficacy of the performance criteria and indicative targets, if based on GDP, is dubious.

Fortunately, there are alternative measures of economic health. Records of government expenditure, balance of payments, timely monetary surveys, and well-audited NBE financial statements can provide insights into the country's economic performance, potentially more accurately than the ambiguous GDP or growth rates. Given the recent focus on monetary and exchange rate policies, these indicators may be more revealing and helpful for policy guidance.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 18,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1268]

Radar | Jul 06,2025

Radar | Feb 27,2021

Viewpoints | Feb 03,2024

My Opinion | Jul 22,2023

Advertorials | Dec 19,2023

My Opinion | Aug 12,2023

Fortune News | Dec 05,2018

Radar | Jan 27,2024

Fortune News | Jul 28,2024

Radar | May 12,2024

Photo Gallery | 178790 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168986 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159834 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137115 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

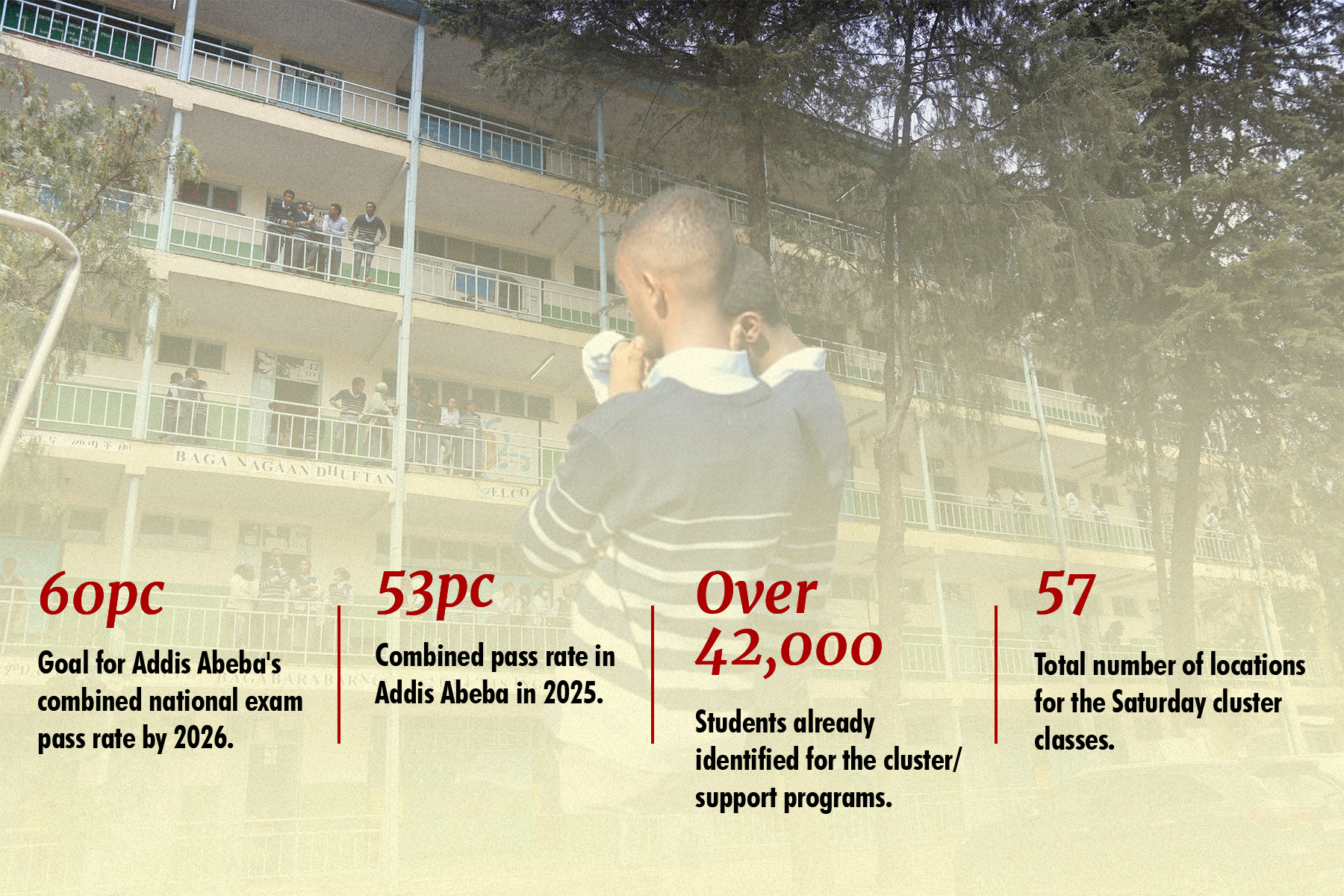

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...