Viewpoints | Jul 22,2023

Mar 5 , 2022.

This decade has not started well for the global community. A once-in-a-century pandemic, COVID-19, inaugurated it and the economic crisis it wrought around the world. Now, a war has come to Europe's doors following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

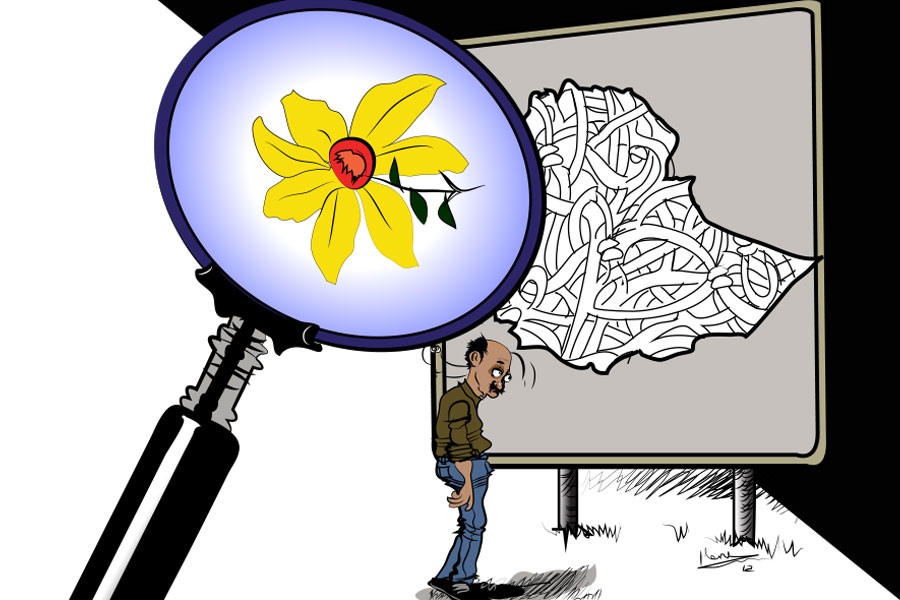

What is unfolding in Ukraine is a war of aggression, as 141 countries agreed last week at the UN general assembly. The world community seems to have been more annoyed with Russia now than when it annexed Crimea back in 2014. Close to 58 countries abstained from voting compared to 35 last week. No less than 28 countries in Africa have accepted the resolution that denounced the Russian invasion of its neighbour. Eritrea stood out as the only African country in voting against the resolution. Ethiopia, whose civil war remains unresolved, passed the moment in history as one of the eight countries whose votes were not recorded.

Even those geographically far from the war zone, many countries have good reason to remain anxious. As the military conflict rages on, chances of an early global economic recovery in the aftermath of the global pandemic are teetering. It would matter little who gains the upper hand militarily. As Ethiopians have learned the hard way (one would hope that they have learned), in needless wars, everyone loses in the end.

Regrettably, Ukraine continues to get devastated, and its infrastructure and cities are razed to the ground, as a million of its citizens are forced to flee.

For its unprovoked attack of a sovereign country, Russia faces punishment through severe sanctions to shut it off from the global financial system. Reserves held by its central bank in the West are frozen. Its major commercial banks have been cut off from a central global messaging system, Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, popularly known as SWIFT.

The result is the Ruble in meltdown. One Birr would buy about 1.5 Rubles in early February. Last week two Rubles were exchanged for one Birr. When a currency falls this fast even compared to the Birr, it is in trouble. In response, the Russian central bank and its Finance Ministry seem to be taking a page out of Ethiopia's. Foreign currency retention from revenues has been lowered to just 20pc, while the repatriation of returns on Russian securities has been prohibited (basically placing capital controls). Interest rates have also been doubled.

For Ethiopians, who have gotten their own problems with political uncertainty, civil war and economic shock, the Russian-Ukraine war could be seen as merely something happening in a distant place but streamed to their homes on TV and through social media feeds. Many may think it unlikely to affect them in any meaningful way. They could be excused for this assumption. Before the era of a globalised world, or even if the war were between countries that were not instrumental to global economic wellbeing, it could have meant little to no effect.

This cannot be the case now. The war in Ukraine will undoubtedly disrupt the global economy in many ways, including the dramatic rise in commodities prices, some of which are crucial for Ethiopia’s economy. It will cause heavy pressure on its balance of payments position, which is in a very precarious state due to the consequential impact of the war in the north.

Ethiopia’s economy is on the receiving end of price rise on three critical commodities: fuel, wheat and fertilisers. These are not just essential items crucial for the economy's survival; they make up for around a third of its import bills.

Oil prices are getting the most attention. There were already projections that prices might spike past 100 dollars a barrel in 2022. The Russia-Ukraine war has made it a reality. The price of crude oil last week reached 114 dollars for a barrel. For net importers of fuel like Ethiopia, this shreds further their scarce foreign currency reserves, which could be around one billion dollars, and enough to pay for a little more than a month's imports. In Ethiopia’s case, as the Administration moves ahead to wean itself from energy subsidies, consumers, left without a cushion, will have to brace for further increases in the cost of living.

Less discussed is wheat. Ukraine and Russia make up a third of global exports of wheat, which are currently at their highest prices in 14 years. Blame the war. Ukraine, one of the top five exporters of the grain, may not harvest in surplus to meet demands from other countries. Sanctions applied to Russia, the third biggest exporter, may mean that other countries cannot buy as much. In the end, it will mean another import bill that will expand for Ethiopia.

But it is not just wheat; agricultural commodities as a whole are expected to rise as the crisis in Europe will affect fertiliser supply, too. Ukraine, Russia and its ally Belarus, already under a barrage of EU sanctions, are some of the top exporters of inputs to manufacture agricultural fertilisers. Sanctions in Belarus and Russia exacerbate the problem as everything that needs to be grown on a farm increases in prices, worsening food insecurity.

These come at a difficult time for Ethiopia. A civil war has hammered down productivity; at a time global supply problems have contributed to a rise in prices that have already created food insecurity for millions of people and threw food inflation to over 40pc. Add to this a drought in the eastern and southern parts of the country.

Ethiopia is overexposed to such calamity because of its low foreign currency reserves. The more vital goods become expensive, the more the Administration is forced to dig deeper into its foreign currency assets. By the Prime Minister's admission, 3.3 billion dollars were spent in the first half of the year to import wheat, fertiliser and oil, double the amount compared to the previous year. It consumes more than the annual revenues from export proceedings. The next six months will likely be more challenging for the foreign currency reserve position.

Ethiopia's economy is already in a perilous situation. Not realising the depth of the problem and failing to acknowledge its devastating outcome appears to be where policymakers in Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's (PhD) administration abdicated their duties. It matters how they respond to the perfect storm that has already gathered steam and begun to fall.

Understandably, their options are limited. Such adversity as in the commodity markets makes it desperate to boost the foreign currency reserve as quickly as possible. But how?

In the immediate, they can expedite the telecom privatisation and liberalisation efforts. It is time to push for third-generation privatisation to include state-owned companies which control the commanding highest of the economy, such as the commercial bank, telecom, the national airline and the shipping enterprise. In deepening the liberalisation of the economy, they can allow foreign investments into the financial sector and attract foreign capital into the telecom sector, issuing more licenses. These all are about targeting foreign capital that is desperately needed.

Foreign capital is reluctant to go to places with political unpredictability, and an active war is raging. Securing negotiated settlement in the civil war and normalising relations with development partners in the West can also be what the political bosses could determine to pursue immediately. Ending the war in the north through negotiated settlement and resolving the insurgency in the south and west could improve productivity in conflict-affected areas. These would help alleviate the calamity in the short term.

The war in Ukraine makes a case for a move away from subsidies, especially on wheat, and orientation towards cash-based welfare support to low-income households. A willingness by subsequent administrations to flood the market with heavily subsidised wheat has dissuaded domestic production, which cannot hope to compete against cheap imports. Not only are the suppliers disincentivised, but such policies have also created an informal market by intermediaries that buy subsidised imports and sell them for higher than price ceilings. Nearly everybody has been losing in this way.

The unintended consequences of the Ukraine war also need to be seen in the context of the past two years. COVID-19 has upended the assumptions underlying globalisation, and the liberal international order as only nation-states seemed capable of responding in meaningful ways while global efforts and institutions floundered. The aftermath of the war in East Europe will further compound the lesson that uncertainty is here to stay. In such a world, institutions like the central bank and the Finance Ministry need to develop strategic thinking and capabilities as challenges arise and give populations they serve to overcome adversities.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 05,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1140]

Viewpoints | Jul 22,2023

My Opinion | Jun 05,2021

Viewpoints | Apr 03,2021

Commentaries | May 11,2019

Life Matters | Jan 23,2021

Viewpoints | Sep 18,2021

Commentaries | May 11,2024

Sunday with Eden | Jul 27,2019

Editorial | Sep 11,2020

Radar | Oct 26,2019

My Opinion | 131819 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128203 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126147 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123767 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...