Fortune News | Jun 08,2025

In Merkato, a troubling quietness dominated the usually lively market last week. Shoppers stroll slowly, pausing briefly to inquire about prices but rarely making purchases. Merchants, once busy attending to customers, sit idly outside their stores, sipping coffee or simply staring, but their faces betraying anxiety and uncertainty about the future.

Merkato caters to every conceivable demand, from "Atkilt Tera," bursting with fresh produce, to "Dubai Tera," stocked with imported electronics. Vendors shout out offers on spices piled high in brilliant heaps, while nearby, fabric merchants unfurl colorful textiles to entice passing tailors. A typical alley might see shopkeepers engaged in animated bargaining sessions, haggling over bulk prices of grain sacks or refurbished refrigerators, evidence of Merkato’s blend of wholesale gravitas and retail vitality.

Shema Tera is one of the 30 sections of Merkato. It suffered a destructive fire six months ago, has shown partial recovery. Reconstruction of the Nebar Building, devastated by the blaze, proceeds slowly. Shops once reduced to ashes have gradually reopened, their owners cautiously optimistic. Some retailers have begun rebuilding shelves; a few businesses have even resumed operations, a manifestation of a fragile recovery.

Amid a sprawling labyrinth of alleys overflowing with textiles, spices, electronics, and produce, tens of thousands of traders rise each morning to engage in an economic ballet at Merkato, Africa's largest open-air marketplace. Covering nearly two square kilometers, Merkato pulsates daily with over 30,000 shops and countless informal stalls, where cash transactions pour in by the billions annually. The market's frenetic activities create both a kaleidoscope of commerce and a logistical nightmare, as traders, hawkers, and buyers jostle shoulder-to-shoulder in a daily ritual of relentless negotiations.

Among these recovering shops is Bunna Tera, a small retail coffee outlet on the Shema Tera line, scuttling modestly as women and children carefully separate good coffee beans from defective ones. However, even here, activity was slow. Conversations fill the silence as much as transactions. Several shops nearby close early due to an absence of customers.

Nonetheless, the sluggish market is not the traders’ sole concern. A tax environment they deem harsh compounds their difficulties.

Mulugeta Abera, a coffee retailer in his 40s, demonstrates this struggle. Recently, he paid 13,000 Br in VAT, a steep jump from his usual 1,000 Br. The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau rejected his submitted receipts, recalculating his sales figures at inflated market rates. He feels indignant about the tax authorities' claim of a kilo of coffee he sold almost double the 400 Br to 800 Br he claimed to have earned. Inflation, too, has eaten up his margins.

“If this continues, I’ll have to close, just like my friends,” he lamented.

Next door to Mulugeta, one shop was sealed by the authorities due to unpaid VAT for three consecutive months, while another closes daily at noon, citing poor sales.

The Revenue Bureau’s recent shift from quarterly to monthly VAT reporting, which businesses claim has mounted pressures on them without accurately reflecting actual sales prices. Mulugeta recalled a recent meeting with local authorities where the Bureau identified approximately 4,000 retailers in Merkato with expired licenses, yet offered no concrete solutions.

Merchants face another unusual pressure: employee income taxes. Despite having no staff, Mulugeta is required to pay taxes calculated for two nonexistent employees, an additional 900 Br monthly. Penalties have surged, with late tax payments incurring fines from 1,000 Br to 3,000 Br, alongside a 4,500 Br fee for business license renewals.

Mulugeta also complained about the operational waste that the Bureau overlooks. From every 100Kg of coffee purchased, he discards about 20pc of defective beans, incurring extra costs of up to 10 Br a kilogram for sorting. These losses are not considered losses by the Bureau, further eroding profits that now hover around a meager 10 Br a kilogram.

“What’s the point of issuing receipts if they won’t accept them?” Mulugeta wondered, voicing frustration at losing regular customers, especially mothers discouraged by soaring prices, driven by a 100pc rise in international coffee markets.

Despite attempts by the authorities to regulate this commercial hub, Merkato thrives largely through informal, cash-based transactions, resistant to documented business. In late 2024, when the city administration mandated that businesses issue official receipts to improve tax collection, Merkato ground to a near halt for over a week as traders vehemently protested. Tax authorities saw revenue slipping through their fingers, but merchants argued fiercely that such formalities disrupt the market’s organic, trust-based system, deeply rooted in decades of tradition.

Across Merkato, complaints of this nature reverberate.

Abebe Ayeno, a clothing vendor in his 60s at Wanza Trade Centre, now opens his shop three hours later than usual due to sluggish sales.

“There’s no reason to open,” he told Fortune, grimly.

Abebe recently paid 7,000 Br in taxes, much higher than in past years. He now feels the tax burden has become intolerable. While he supports fair taxation, Abebe argues that the current system disproportionately burdens businesses registered for VAT compared to those paying lump-sum taxes. The Bureau’s ambitious revenue target of 234 billion Br from the market appears unrealistic to him.

Abebe battles rising competition from illicit traders, who increasingly dominate the market due to lighter tax burdens. Administrative issues heighten vendors' frustrations, with inspections failing to acknowledge declining sales.

“Their pen is pushing us to the brink of closing our businesses,” Abebe said, referring to the tax amount the officials write and stating the toll this stress has taken on his health.

A seller of children’s clothing and bags, requesting anonymity, echoed Abebe’s feelings. This attitude has driven more legal traders toward the parallel market, escaping crushing taxes. He, too, struggles, relying on financial support from his brother abroad to settle his tax bills. A younger employee, whose father traded in Merkato for 45 years, recently shut his shop due to overwhelming tax pressures. With mounting costs and dwindling margins, the anonymous vendor's shelves remained largely empty last week.

Such disputes over market-value taxation are not new. Six months ago, vehicle importers faced similar issues, leading 41 importers to sue the Revenue Bureau over a new fixed pricing formula meant to curb tax evasion. The Federal High Court temporarily suspended these standards in December 2024, though the issue remains unresolved.

The Bureau’s stringent regulations extend across various sectors in Merkato, which is known to be a wholesale nerve centre, a crucial junction in the country's supply chain.

The agricultural output such as coffee beans, pulses, and spices, land here first, traded in bulk by savvy intermediaries before dispersing across the capital and beyond. Goods arriving pass through Merkato before distribution nationwide. After customs clearance, everything from South Korean televisions to Chinese footwear filters through this marketplace, bound for regional retailers. So is this true for domestically produced and manufactured goods such as textiles.

According to Goshu Negash, president of the Ethiopian Textile & Garment Manufacturers Association, the Bureau demands VAT payments based on inflated valuations. Uniform shirts, sold at 600 Br, are assessed by the Bureau at 2,000 Br, making sales nearly impossible. Companies in his industry have delayed employee income tax payments for four months, hoping for regulatory relief. However, the looming accumulation of penalties and interest weighs heavily on manufacturers.

The petroleum industry faces similar predicaments.

Ephrem Tesfaye, a board member of the Ethiopian Petroleum Dealers Association, echoed the struggles faced by gas stations. Pump attendants earn less than 1,000 Br monthly, largely dependent on tips, yet the Bureau’s tax assessments do not reflect this. Ephrem warned that rigid tax enforcement could force stations to downsize, negatively impacting employees' livelihoods and performance.

Tofik Awel, a pump attendant at an Oil Libya branch in the Denbel area, has already experienced cuts in his earnings — from 800 Br to 300 Br monthly — due to the rise in electronic payments. Unable to sustain himself, Tofik is considering returning to work for restaurants and cafés.

Zahara Mohammed, secretary general of the Addis Abeba Chamber of Commerce & Sectoral Associations, noted a worrying erosion of trust between businesses and the Bureau. She criticised the Bureau’s frequent dismissal of receipts, a practice pushing many into the parallel market, undermining legitimate businesses.

Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau officials dismissed these outcries, categorising them merely as administrative tasks. Sewnet Ayele, head of communications at the Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau, defended the Bureau’s enforcement procedures. Sewnet claims extensive studies covering market prices for over 2,000 commodities justify the tax rates. He asserted the Bureau’s legal authority to set these market prices, arguing their necessity to combat rampant tax evasion.

Over the past eight months, the Bureau handled approximately 12,000 appeals from taxpayers, accepting 52pc of them. He argued that the new VAT payment system would promote transparency and reduce corruption.

However, tax expert Biruk Negusse disagreed with the Bureau’s approach. He argued that broad market pricing determinations are inappropriate, legally intended only for specific cases involving related parties. Instead, Biruk urged that taxes should reflect individual transactions documented accurately, rather than blanket estimations.

Despite criticisms, the federal government remains determined to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio by four percentage points to 11pc by the fiscal year 2027/28. The authorities see strengthening the VAT system as crucial, hoping to boost domestic revenue and reverse declining tax income. However, Merkato’s businesses fear these ambitious reforms, as currently structured, may instead suffocate their livelihoods, pushing more traders into financial despair and informal markets, threatening the very economic activities local and federal authorities seek to tax.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 13, 2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1302]

Fortune News | Jun 08,2025

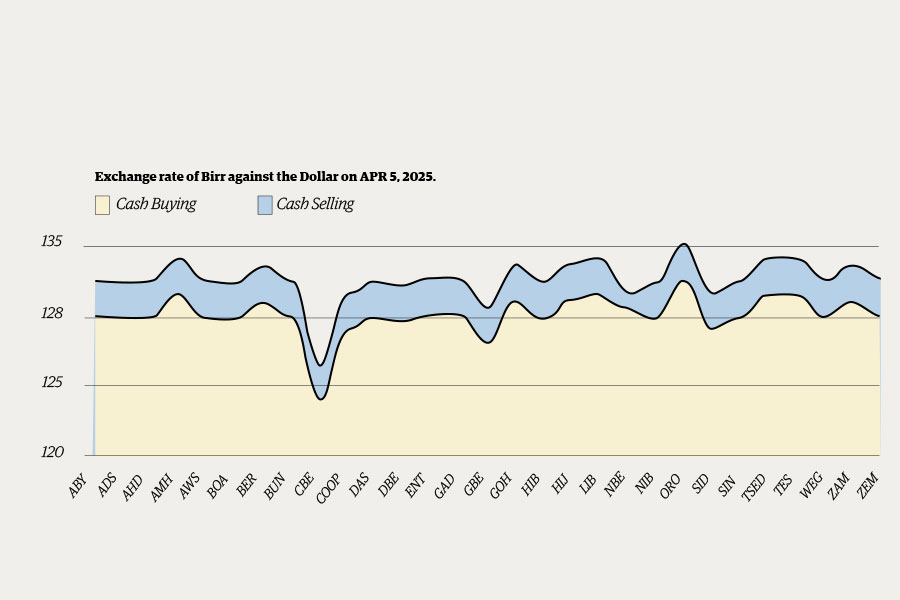

Money Market Watch | Apr 27,2025

Fortune News | May 08,2021

Agenda | Dec 28,2019

Commentaries | Jan 28,2023

Fortune News | Jul 18,2020

Commentaries | Jul 10,2020

Commentaries | Feb 13,2021

Commentaries | Nov 25,2023

Editorial | Jun 22,2024

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...