Feb 6 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

There was once a country that went through untold suffering after a military junta unleashed a campaign of political terror against its people. Many perished, a generation was stunted, and the several ethnic groups that made up the country seemed to have been irrevocably pitted against one another. But this country eventually dug itself out of the hole and made its way toward the light. Its economy opened, instituted liberal reforms and its leader, amazingly enough, has a Nobel Peace Prize.

Recently, the world declared – at least the West – that all of the progress has been for nothing. Conflict broke out, hundreds of thousands were displaced, crimes against humanity were reported, and its leader’s moral scruples were questioned. Some asked for the Nobel Peace Prize to be revoked.

That country is not Ethiopia but Myanmar, a Southeast Asian nation. Last week, it featured in the news as the West felt that it had lost another country to the mystic powers of authoritarianism when what amounts to its Prime Minister, Aung San Suu Kyi, was detained by the military. Power resides with the armed forces in that country, or whom a quarter of the seats in parliament are reserved.

It is interesting to consider how the international community looks upon Myanmar to comprehend the world’s reaction to the armed conflict in Ethiopia's northern region. It is a tale of short memories and the collision of forces nonaligned with Western ideals combined with a genuine worry for citizens' wellbeing.

Like in Ethiopia, the country’s political and economic opening up was much lauded. It started in the early 2010s, back when liberal internationalists still fantasised about the compatibility of Western-style democracy with the domestic realities of ethnically heterogeneous low-income countries. It was a time when the Arab Spring had yet not gone sideways or that the democracy of countries such as the United States looked as steady as a rock.

But Myanmar continued to beat the odds. Three decades ago, San Suu Kyi rose to prominence during democracy protests, and the West immediately fell in love with her. A female freedom fighter who had been under house arrest for 15 years, boldly facing down a military junta – this is a Hollywood story. When she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, which she could not accept due to being under house arrest at the time, and used the money to build a hospital, the West was awed. When she declared that non-violence is not merely a moral principle but a “practical” and “political” one, the world rejoiced.

When she finally became State Counsellor in 2016, it was an unlikely romance finally requited between Myanmar and the West.

But it was not a marriage made in heaven. Like young lovers that rush to matrimony, these two were not ready for soul searching. No less, they only liked the idea of one another – Myanmar liked the attention, and the West thought it had found another country it can sculpt in its image.

What the West did not get was that “Myanmar’s problems went far deeper than a simple absence of democratic elections,” as Sebastian Strangio, a journalist covering Southeast Asia, wrote in Foreign Affairsmagazine. “In practice, the sudden appearance of freedom of expression and competitive politics stoked ‘older anxieties around race, religion, and national identity.’”

Sound familiar?

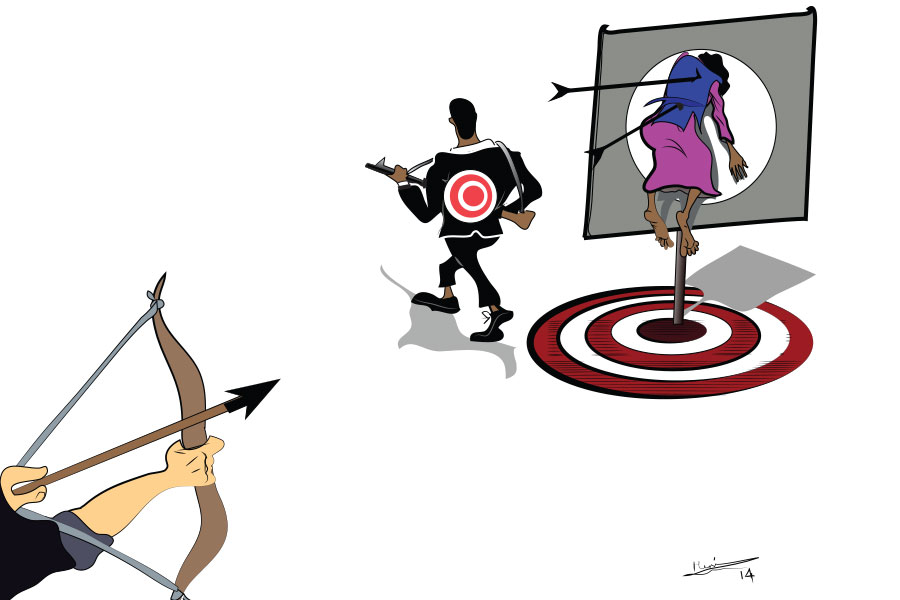

The story of the West romantically adventuring – militarily or through means of soft power and diplomacy - into a country that it barely understands has become a cliche.

The first signs that the relationship was fraying came in the aftermath of the refugee crisis created after a militant group attacked the country’s military. The latter responded with disproportional violence that sent hundreds of thousands of a minority group called Rohingya to flee across the border into Bangladesh.

There was an international outcry. The West looked to San Suu Kyi, and she spurned it. First, she was mute over the issue. Then she began to defend the military for its actions. No one could believe it. The romance turned into bitterness and then to disdain. The West even considered asking for the matrimonial ring – the Nobel Peace Prize – back.

But the feelings never went away. When the military detained her, claiming that she was re-elected through fraudulent means, the West came to her defence once again. It asked for her immediate release and reinstatement as head of government. Unfortunately, it did not reconsider its own behaviour and choices. It could not believe that its own norms and values could not be exported into a country that neither has the history, nor even the interest. Myanmar likes the attention; the responsibility of overhauling its traditions and habits is another matter.

Ethiopia is not all that different in its relationship with those countries that derived their national myths and social character from the legacies of ancient Rome and Greece and the European Renaissance.

The West has had a love-hate relationship with Ethiopia. The only moment of consistency was during the Dergue'sreign. Most other times, it is complicated. It finds exotic, even romantic, that its core is made up of an ancient Christian, African-majority empire. But the West’s revolutionary mission and notions of self-determination - especially in academic circles that are overshadowed with the French export of post-modernism - make it baulk at the impression that the empire still lives in some form. This idealism also brings it into frequent collision with other states that emerged as empires like Russia and China.

But no great romance story is without its ups and downs. Ethiopia and Myanmar continue to be flirty, and the West could never really be content with themselves. At the very least, the latter has to continue to sell goods and services to the rest of the world and import raw materials and cheap labour in return – the very logic of capitalism that drove Western imperialism.

History has yet to show where all of this will end.

Christian Tesfaye (christian.tesfaye@addisfortune.net) is a researcher and Fortune'sOp-Ed Editor whose interests run amok in the directions of both print and audiovisual storytelling.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 06,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1084]

Radar | Jun 17,2023

Sunday with Eden | Jan 18,2019

Advertorials | Jun 05,2023

Fortune News | Jul 15,2023

Editorial | Oct 23,2021

My Opinion | 131451 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127803 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125783 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123419 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...