Commentaries | May 14,2022

May 23 , 2021

There is no disagreement as to the global nature of corruption and fraud, which require global solutions. International financial institutions (IFIs) are no different in the accountability mechanisms they apply in carrying out projects in countries such as Ethiopia, writes Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn (yehuala5779@gmail.com), adjunct lecturer at Addis Abeba University and an associate at MTA.

International Financial Institutions (IFIs) are defined as bodies established by agreement between two or more countries in the form of a charter, constitution, or convention. They are intergovernmental since they are the creation of agreements amongst states, and their power and mandate emanate from international agreements.

Accountability mechanisms under IFIs are an avenue for private individuals and groups to file claims against the institution(s) for redressing their grievances on poorly designed and implemented projects.

There is no disagreement as to the global nature of corruption and fraud which require global solutions. IFIs are not different in this respect. This was well noted when the then World Bank president, James Wolfensohn, said that “we need to deal with the cancer of corruption” and “adopt a zero-tolerance approach” towards corruption. As a result, there was a consensus on the establishment of citizen-driven accountability mechanisms for IFIs.

The World Bank has the distinction of being the first IFI to develop accountability mechanisms to enhance its effectiveness. In the 1990s, the Bank was hit by outcry and protest because of maladministration and corruption. By that time, the local and global campaigners from different parts of the world started to gain greater attraction, helping them to exert leverage. On top of this, the donor countries notified the Bank that unless it enhances its transparency and accountability, they will freeze the money they donate. After such relentless pressure, the World Bank was forced to form an Inspection Panel in 1993.

Although external pressure was the principal factor for this, it is difficult to rule out the importance of internal board pressure as well. The Panel is composed of three independent members from different nationalities that are appointed by the executive directors of the World Bank. Generally, the whole process in the Panel can be broadly classified into three: registration, eligibility, and investigation. Its purpose is to carry out investigations to measure the level of compliance. For instance, an executive director may, in the particular case of alleged severe violations of such policies and procedures, ask the Panel for an investigation and the Board may at any time instruct it to conduct an investigation. Under this process, a single party is not qualified as a requester, but two or more persons with a common concern.

Once the Bank receives the claim from the people, it rarely considers the claimant's interest to resolve the matter. This makes the whole process at the Inspection Panel to be geared more towards compliance orientation rather than problem-solving. A combination of two approaches was recommended to address this: compliance review and problem-solving through the instrumentality of creating an independent institution. The formation of a Compliance Review & Problem-Solving Mechanism (CRPSM) was suggested, which would have, among other things, both compliance review function and could undertake a problem-solving exercise.

The power and jurisdiction of the Inspection Panel are limited to the International Bank for Reconstruction & Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA). The other members of the World Bank Group - such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which exclusively deal with private parties, are not subject to scrutiny. As a result of external pressure, however, the World Bank was forced to establish the office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO).

Unlike the Inspection Panel, CAO adopts a less rigid and punitive approach and one that is more flexible and settlement-oriented. With its three main functions: advisory, ombudsman and compliance, the CAO allows a single party to make requests. It should be noted that, as provided under the operational manual, the CAO is not serving as a substitution for international court or the national courts in the host state.

Other financial institutions have walked the path the World Bank has when it comes to establishing accountability mechanisms. With the view of serving as a forum for project beneficiaries to appeal to an independent body, in 1995 the Africa Developmental Bank's (AfDB) Board of Directors approved the establishment of an inspection function. Although it was designed in a similar fashion to that of World Bank’s, it was not established under a standing panel with a separate secretary. There were no surprises when the Board became unsatisfied with the effectiveness of the inspection function and replaced it with a new accountability mechanism which came into force in 2003.

The new one focuses on both compliance review and problem-solving, which are performed through project consultations. Its main function is to review and assesses complaints, collate, integrate internal and external experiences of problem-solving, and provide generic support and advice for operational development in their problem-solving activities.

All in all, accountability mechanisms have thus, over the years, proven their merit. Though the birth of IFIs can be traced back to the Bretton Woods agreement, no accountability mechanisms were in place until the 1990s. Their roles in development and reconstruction have evolved, although the criticisms have barely ever ceased. They are not perfect but neither are they discardable.

PUBLISHED ON

May 23,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1099]

Commentaries | May 14,2022

Fortune News | Feb 29,2020

Radar | Aug 22,2020

Radar | May 23,2021

Radar | May 07,2022

Editorial | May 15,2021

Radar | Feb 26,2022

Fortune News | Sep 11,2020

Viewpoints | Jan 28,2023

Fortune News | Dec 19,2021

My Opinion | 131584 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127940 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125915 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123539 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

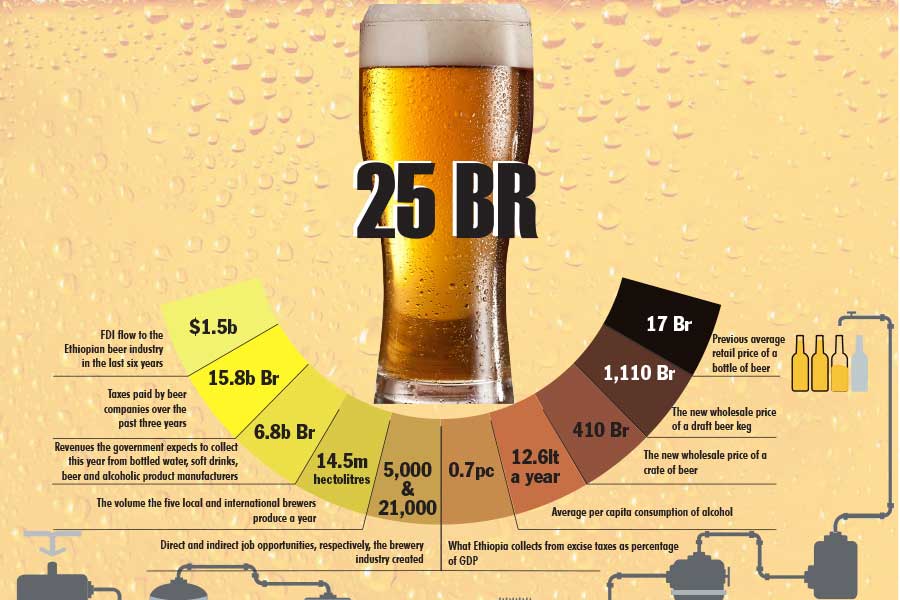

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...