May 15 , 2021.

Gradually, the biggest and most visible billboards in Addis Abeba have become political campaign ads. The most visible, like its former incarnation in past elections is the Prosperity Party (PP), with billboards advertising candidates over a characteristic blue background. Peculiarly, the education of its members is stated without fail, as if there is something about politics in Ethiopia in its current form that leads the incumbent to assume that any premium is placed over tertiary level credentials.

The Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (EZEMA) is also trying to hold its ground in the visibility league, though not as successfully. Still, it is perhaps the only opposition party left running in the upcoming elections with deep pockets. And with the second largest number of candidates at 1,385. Of the 46 political parties contesting the elections slated for June 5, the lead is held by the Prosperitians, which have fielded 2,432 candidates. EZEMA even attempts to be as loud as the Prosperiterians, with its campaign buses being constantly sighted along the main roads.

Much more muted participants in the elections, though still breathing, are Balderas Party, of the incarcerated Eskinder Nega`s fame; and, even the old Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP).

But, for all of the noise some of these parties are making, it is no match for the uncertainty felt down the surface. Ironically, the elections have added to this, instead of alleviating the popular anxiety as there is fear that they would be considered inconclusive. The tug and pull for power would continue into the foreseeable future with all the political crises in store manifesting themselves in violence.

It is a situation that has the likes of the European Union (EU) worried. But, it is hardly a concern without reasons as the country faces security issues on multiple fronts.

Nonetheless, the chances that the elections would be postponed appear to be remote. Birtukan Midekssa and her colleagues at the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) may be tempted to push it by a few days or weeks, as they did with deadlines for voters` registration. With much investment in the logistics and technicalities of the process where millions have been registered, and billions of Birr are spent, electioneering has reached a point of no return.

This, though has not stopped the grumbling, especially considering one of the most overriding issues that make holding elections possible - the security situation in the country, or the lack thereof.

There is a military conflict - a civil war - active in Tigray where over 2.7 million eligible voters will not participate in the June elections. Come next October, when a new government (or coalition of a sort) is formed, Parliament will have 38 seats less than the 547 representatives it should have, thus excluding an entire population of a regional state from a political and legislative process of highest order. Add to this chronic instabilities in pockets of the Amhara and Benishangul-Gumuz regional states, if not unrelenting violence in Western Wellega Zone of the Oromia Regional State.

With Ethiopia emerging as one of the top 10 trouble spots to watch in 2021, there is little clarity on what may happen on the days leading up to and beyond polling day in early June. Even if polling concludes without disturbances significant enough to disrupt voters from going to the polls, there is the question of its inclusiveness and conclusiveness. It will be the most momentous test to the ability of the post-election coalition to govern. Indeed, the skeptics may have a point when they hold the view that there may be no overriding reason to hold elections, at least not now. Given the significant security risks the country is confronted with, and the real possibilities that opposing groups for political power would fail to find it conclusive, it is an argument too valid to simply ignore.

Partly, this is because of the nature of the political exercise that has unfolded over the past half a decade. In 2016, the first state of emergency was imposed, and two years later, Abiy Ahmed (PhD) was sworn in before Parliament as the third Prime Minister since the mid-1990s. This followed with many promises, a slew of legal reforms, ministerial reshuffles, detente and later tensions with oppositions, conflicts and wars. Matters have only gotten worse, with no end in sight. In a country that lacks revered institutions and social cohesiveness, it takes an extraordinary type of optimist to believe that next year or the years after promise better grounds for credible elections in the process and have a legitimate government in its outcome.

It is not only that pushing these elections would be akin to delaying pain; it is not even clear under what grounds it could be done and what sorts of uncertainties will arise as a result. The unique circumstance of Ethiopia’s constitution dictates that there is no clear way to go about postponing elections. Prime Minister Abiy`s administration, with its enablers in high offices, had squandered a rare opportunity to amend this part of the constitution last year, instead opting for interpretation. It had required the sort of constitutional acrobatics that seemed so unacceptable to the political force in Tigray that, combined with other factors, it led to a regrettable and tragic war.

With a broken political discourse that is uglier than ever and an absence of trustworthy constitutional institutions, another major conflict may be unavoidable, if not handled wisely.

While elections are not full proof to secure political certainty, they have a far greater chance to install a government than their absence could. Where government has its monopoly of violence significantly threatened, the purpose of these elections more than anything is to guarantee that the state's cohesiveness and security is not left to chance. It is not a matter of choosing who gets to govern; with the privatisation and regularisation of violence, the elections should be about whether anyone can govern.

The post-elections period would also need careful considerations, especially in the treatment of opposition parties. Of the 48 political parties in the registry of the electoral board, two parties with broad support in Oromia Regional State have boycotted the elections. Their leaders and followers under arrest, such as Jawar Mohammed and Bekele Gerba, and several of their offices closed, the OLF and OFC are sidelined as the case is with the TPLF, the latter designated by Parliament two weeks ago as a terrorist organisation.

The discourse in the post-elections setting could contemplate a political roadmap for cessation of hostilities while bringing onboard the sidelined political forces back to the mainstream political platform. Granted, non-electoral political engagement may not make up for actual representation in the power corridors of the state. But, it can offer these forces a voice and a say in how the country is governed, provided that those at the helm of power engage their foes for a durable political settlement, in good faith. The very start of such negotiations for political settlement could mean something in breaking the stalemate.

Politics should be the art of the possible as the miscarriaged attempt in 2019 tried. Parties signed a code of conduct vowing to discipline themselves and behave in their political activities according to agreed-upon rules and guidelines. Over 100 of them, including the incumbent at the time, the EPRDF, have signed the document with pomp and ceremony at the Hilton Hotel, where the Prime Minister was present. Fast forward two years later, and the accord is not even worth the paper it was written on. This can be resurrected, especially if those who come to public office after the polls promise to be bound by the code of conduct and the Council`s decisions the signatories set up.

When the elections are said and done, the polls are closed, the winners declared, and a new parliamentary session begins, there would also be the question of what will happen in the Tigray region. It is the elephant in the room; huge, filling up the whole space and ironically ignored in the political discourse during the electoral debates. It is an utter manifestation of the pretense that is almost everything is Ethiopia today. The Tigray-factor has been taken for granted that the legislative houses will continue to lack a constituency much the same way they have done this year.

It would be nothing less than a shortage of political imagination and an abdication of duty by the state, if not a betrayal of an entire population, to leave the matter of self-governance and shared rule to the security situation in the region. To pretend that it does not exist or to take it for granted that the region would continue in the manner it is doing now will only continue to be symbolic of the moral degeneration of the country's politics.

Beyond the characteristic bravado that disloyalty to the state cannot stand, concerted efforts should be put on how ceasefire could be achieved and what political roadmap would most make it possible to have dialogue to bring lasting political settlement.

PUBLISHED ON

May 15,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1098]

Agenda | May 23,2021

Viewpoints | Dec 19,2021

Fortune News | Jul 18,2021

Radar | Oct 09,2021

Radar | Sep 04,2021

My Opinion | 108813 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 105210 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 104020 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 103320 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transportin...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

The cracks in Ethiopia's higher education system were laid bare during a synthesis re...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Construction authorities have unveiled a price adjustment implementation manual for s...

Jul 13 , 2024

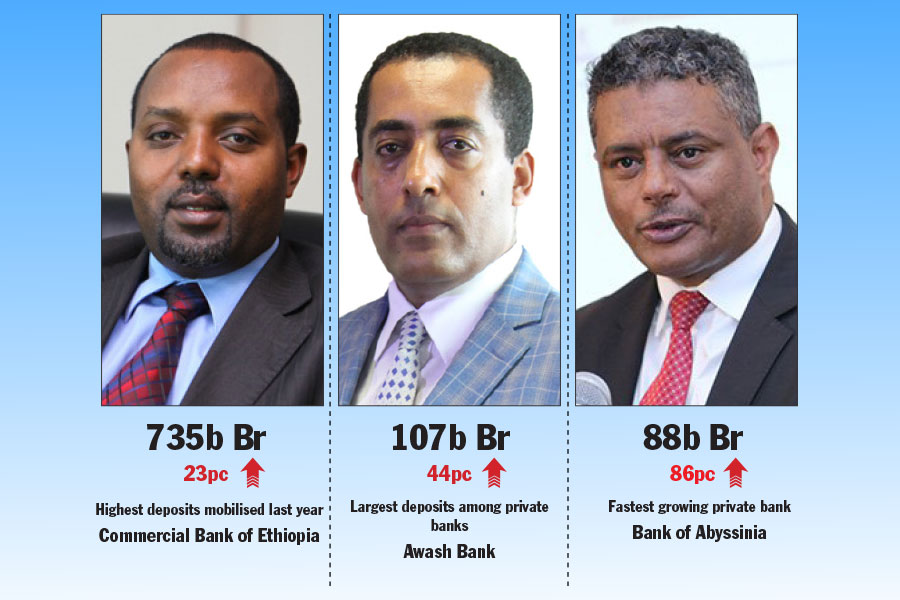

The banking industry is experiencing a transformative period under the oversight of N...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

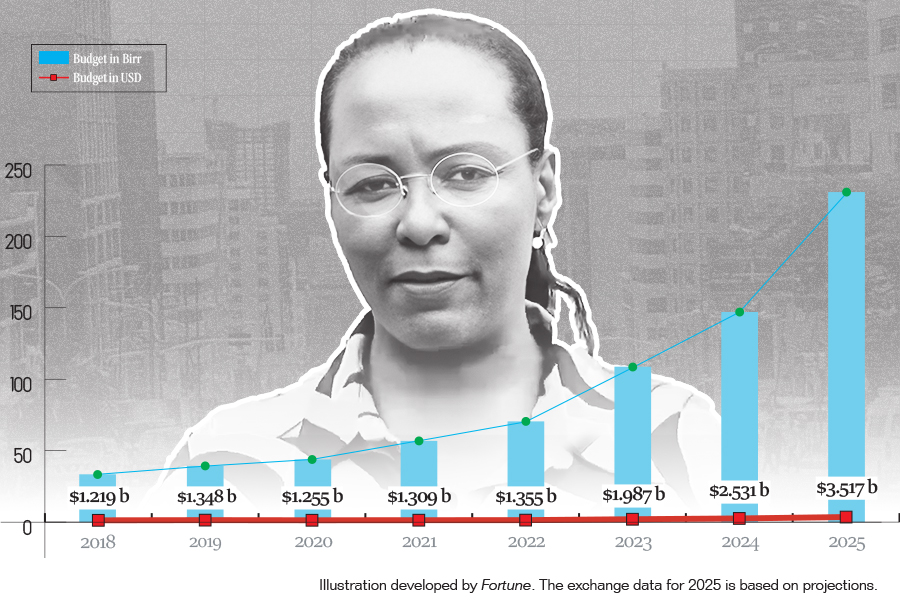

Mayor Adanech Abebie's Administration faced an audit report that unveiled a startling...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Brook Taye (PhD), director general of the Ethiopian Capital Market Authority, has tak...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's horticulture, a major source of foreign currency and employment, is facing...

Jul 21 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Commercial banks are now permitted to acquire equity shares in capital market service...