Sunday with Eden | Jun 05,2021

Apr 22 , 2022

By Demissie Gudeta

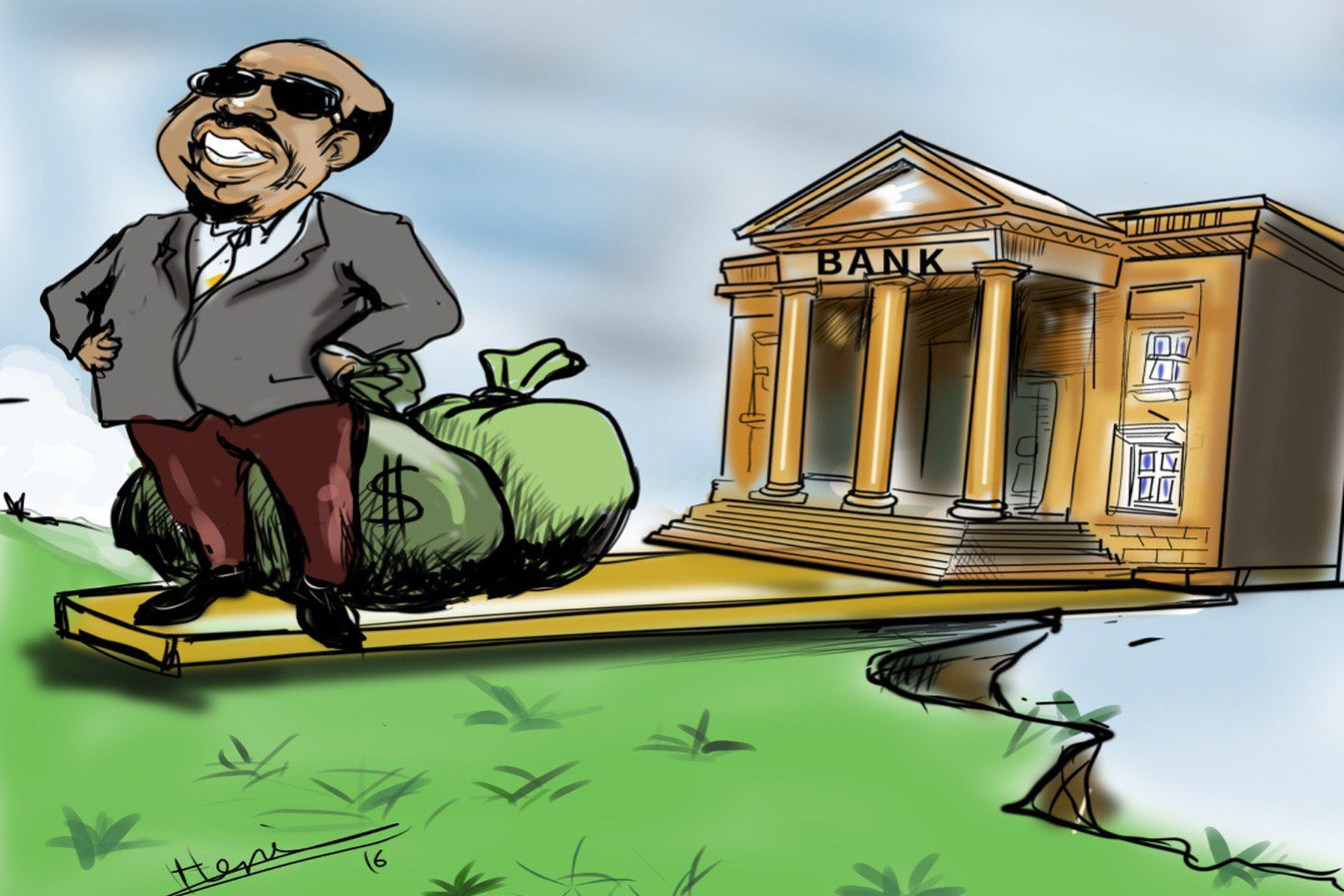

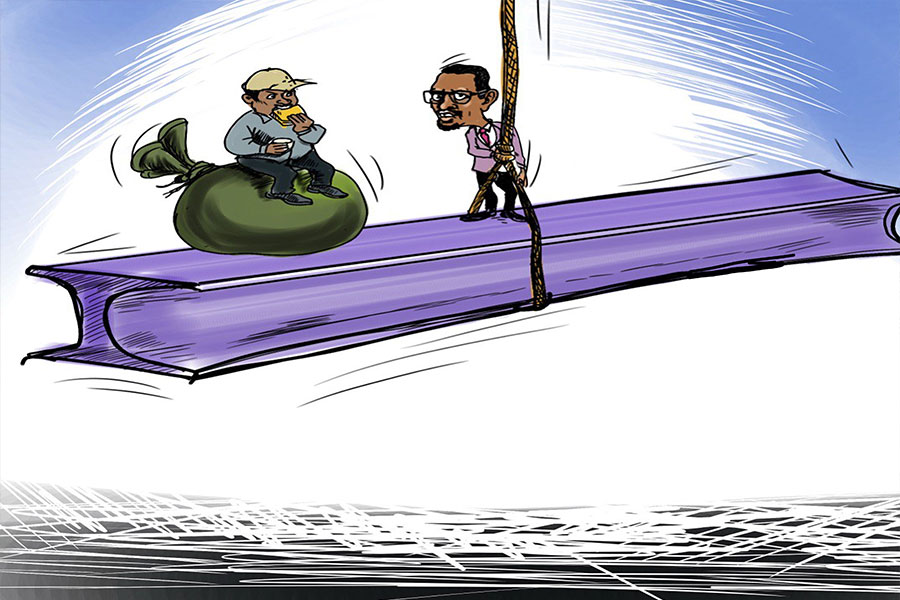

Banks are asking for too much – savings paying negative real interest rates, the autonomy to spread the funds and high service charges. On top of this, they dare to preach the dangers of foreign competition, writes Demissie Gudeta (demissie.gudeta77@gmail.com), former Ethiopian banker who lives in the US with an interest in banking and stock markets.

There is an ongoing debate on whether foreign financial institutions should be allowed to operate in Ethiopia. At the forefront of the argument are bank board members and executives. Financial liberalisations might increase financial fragility at face value, making the country prone to periodic financial and currency crises. The chances are that developing countries like Ethiopia could be on the receiving end of volatilities in opening up, though not always.

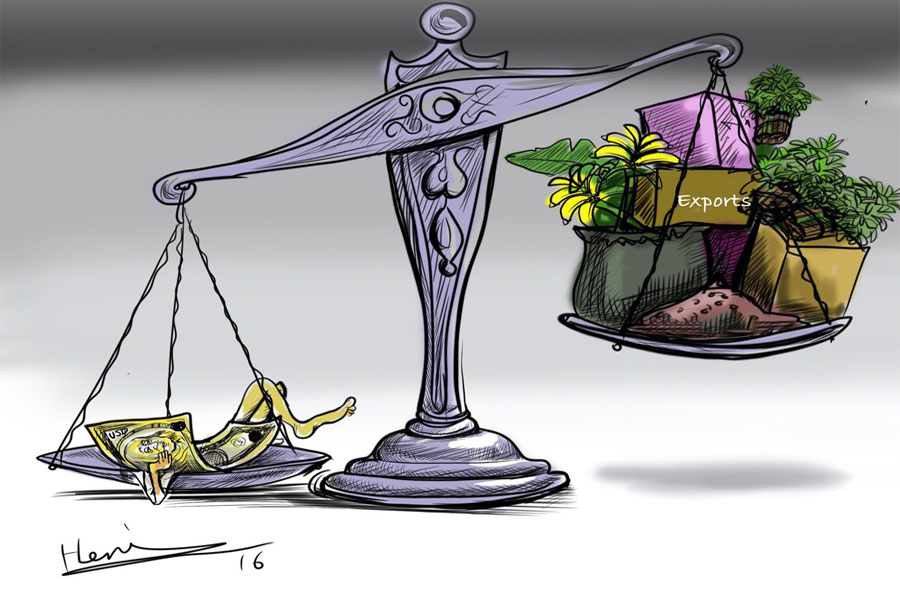

But a question remains largely unasked on the harm existing private commercial banks inflict on the economy. Domestic banks are no less detrimental when seen from financial stability and income distribution.

Take the 10-Year Perspective Development Plan recently introduced. Sustainable finance is considered a major enabler of growth. The plan singles out the government’s pursuit of empowering the private sector in significant public investments. In a way, the private financial institutions, banks in particular, could be on the receiving end of this generous consideration. The intention could be that they are to be expected to deliver what they promise to shareholders and the public – namely sustainability.

Sustainability is not about investing considerable sums in employing international consultants to conduct a strategic plan that comes up with irrational recommendations such as downplaying the role of employees and, in contrast, inflating top management salaries. Neither does it mean having a different logo. It must be about ensuring the long-term health of their respective companies by enhancing competitiveness and being responsive to regulatory and environmental demands.

If the government spends public money to create a sustainable financial sector before changes in the way these institutions behave, it will simply be nurturing irresponsible actors.

When I was a senior officer at a commercial bank, some time ago, my boss made a statement that I thought was a banker’s conviction of the market. We argued about the demand elasticity of interest rates.

“This is a suppliers’ market," he said. "Whatever it is that you supply at your desired price, you can sell it. It is getting the loan that concerns them [borrowers]. As you can see, we have queues of requests to deliberate on and approve. They might not know the interest rate for that matter – even at the time of signing the contract.”

This highlighted how downright irresponsible it is to exercise monopolistic power in a financial sector in its infancy. More importantly, it ignored the very notion that having an informed customer helps grow the industry – where banks could compete on a more permanent engine of growth – instead of the pursuit of hit and run.

We might please shareholders with annual profits, but do we really increase shareholder value?

The shareholder might happen to be a customer of one of the hard-done clients of these banks that pays inflated interest on its loans and makes every effort at its disposal to pass down the costs to consumers.

What about corporate social responsibility – in the sense of its mere utterings – apart from its colourful presentation on websites?

Irresponsibility was extremely visible during the COVID-19 outbreak and the disaster responses of some of the institutions. Some institutions made public announcements of interest reduction in sectors where they barely do business or have the least portfolio. What a response it is! How responsible! Meanwhile, they make every effort to make sure they hold less provision to “increase” shareholder profit – by rescheduling, restructuring and extending non-performing loans under the pretext of COVID-19.

They are practically making their own cashflows unbearably challenging to manage. Waiving loan repayments and effecting dividend payouts on “artificial” profits on those ‘healthy’ loans could make a recovery near-impossible and a liquidity crisis imminent.

We should wonder, then, how bank executives get the courage to preach the dangers of opening up the financial sector to foreign players. The latter might have some downsides to bring, but it cannot be more significant and profound than the undesirable socio-economic effects of the local private banks. A bank cannot claim to be socially responsible if it lends savings at double the interest rate it pays to customers. All the while, some banks are paying more than 14pc for fixed time deposits.

Why the overtrading in the first place? What more damage can they bring to the nation than this? Does this not promote speculation than entrepreneurship?

A Bank cannot claim transparency when it literally “cheats” shareholders with questionable financial statements every June. A bank cannot claim to be a valuable player in the country's economy when it lends public money to the few in the business community that have the right network or own collateral. Entrepreneurs with feasible business ideas are rejected outright for insufficient collateral, whereas those few businessmen are generously granted unsecured loans even for “loan settlement” and on relatively flexible terms.

A move to introduce a depositor insurance scheme to safeguard the public in times of crisis, such as liquidity issues, should be welcomed. But the National Bank of Ethiopia's (NBE) failure to work on the possible root causes of the problem, and instead establishing a fire brigade, should be questioned. Unless they do not want to name it, many economic hardships have their inception at private commercial banks and the central bank cannot pretend it cannot see the problem.

Most banks maintain an outstanding loan portfolio that is 10-fold their paid-up capital. An overwhelming majority of whatever they lend to the selected few is neither their own capital nor asset. It is savings. It is our fund, our deposit. Yet, they do little to promote entrepreneurship or give back to the society they “exploit.” Inflation and market malfunctioning are brewed and enabled in what is a flawed and failed banking system.

I also welcome the move from the Ministry of Finance on the decision to keep public funds public. Let them work on financial literacy campaigns, float shares indiscriminately to the public, and raise the necessary funds to operate on their own. For good reasons, state-owned banks charge less interest than their private counterparts. It might sound that public banks are not accessible to credit for SMEs and that the fund might not serve the purpose it could had it been with private banks. The thing is, SMEs and entrepreneurs have no access here either. They reserve the funds for a selected few most of the time.

The private commercial banks are asking for too much – savings paying negative real interest rates, the autonomy to spread the funds of their own will, the liberty to higher service charges, and being shielded from foreign competition. The choice we are presented with now is between domestic or foreign bank exploitation. The name does not matter so long as we are being abused. We should not be afraid of financial liberalisation as we have been made less sensitive to exploitation. Obviously, the local "sharks" face an existential threat with market opening up. For us, it would only be a regime change that would not make a difference.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 22,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1147]

Sunday with Eden | Jun 05,2021

Radar | Jun 20,2020

Fortune News | Mar 12,2022

Fortune News | Sep 11,2020

Radar | Dec 02,2023

Featured | Oct 25,2020

Agenda | Feb 19,2022

Films Review | Jan 07,2022

Fortune News | Feb 09,2019

Radar |

Photo Gallery | 96795 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88976 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67184 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65766 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 20 , 2024

In a departure from its traditionally opaque practices, the National Bank of Ethiopia...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Apr 20 , 2024

Ethiopia's economic reform negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in their fourth round, taking place in Washington, D...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By BERSABEH GEBRE

An undercurrent of controversy surrounds the appointment of founding members of Amhara Bank after regulat...

An ambitious cooperative housing initiative designed to provide thousands with affordable homes is mired...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's juice manufacturers confront formidable economic challenges following the reclassification of...