Dec 5 , 2018

By

Since April 2018, a new optimism is visible in urban Ethiopia. Local intelligentsia and alike have warmly welcomed the change in the national leadership. Ethiopian press seems to be enjoying new found freedom by printing “suggestive write-ups,” which is a good sign of the nation’s march toward matured democracy.

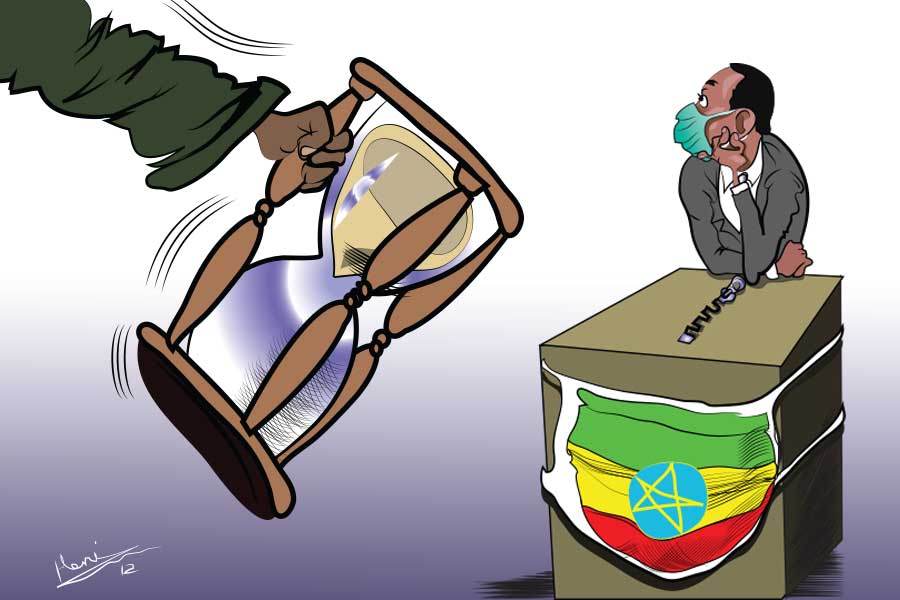

During the past nine months, the new leadership has followed a pointed agenda of upholding the supremacy of law, institution building and undertaking a grand corruption and human right's abuse probe. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) has appealed to unite the nation with love and forgiveness. Only time will tell the effectiveness of his appeal. Nevertheless, the ills of yesteryears cannot be overcome unless the administration refocuses on microeconomic growth and development.

Ethiopia today has the distinction of being the second most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa but ranks seventh in gross domestic product (GDP). A large population is always a wealth rather than a hindrance in growth – some of the world’s fastest-growing economies, especially India and China, have taken the top ranks when the population is concerned.

Only human development leads to economic growth though. Unfortunately, Ethiopia’s erstwhile planners have attached great importance to the macro scene rather than micro challenges. The result has been uneven annual per capita growth, thereby reducing the competitiveness of the population.

A growing population needs skills, training and employment. An unskilled population pushes the nation into a downward slide. While the World Bank has complemented Ethiopia for the reorientation of the budget from recurrent expenditures to capital improvements and a significant devolution of resources from the federal government to regions, its heavy spending on infrastructure, especially out of borrowed funds, has resulted in a skewed socio-economic transformation.

Public infrastructure has not been productive simply because users' ability to pay is low. Alternately, higher spending on education and health should create a class of people that contribute to faster economic development.

An analysis of a decade of historical budgetary provisions reveals a sad picture of amounts provided and spent on health and education. For instance, between 2009 and 2014, recurring and capital expenditures as a percentage of GDP have declined. This evidence suggests that the quality and quantity of funds spent so far did not have adequate potential to meet the development challenges of the growing youth population.

The situation is also reflected in the growth of the services sector, which has been contributing negatively to overall economic growth. No economist propounds growth of the services sector at the cost of the agriculture sector. Nevertheless, the stark reality is that the importance of the services sector, comprising financial services, hospitality and transportation, has gained all over the world at the expense of traditional sectors.

The process of development usually coincides with a growing role of services in the economy. For Ethiopia, the question is not whether to move into services, but how and at what speed to move into services. By introducing dynamic human development measures, Ethiopia’s service sector can easily increase GDP growth by two to three percentage points with the service sector occupying 60pc to 62pc of GDP. Moderate liberalisation in the financial services sector alone can generate thousands of opportunities and jobs locally.

The new administration of Prime Minister Abiy has an amazing opportunity to reverse Ethiopia’s historic economic trends and lead the country into a development era that will encompass the young population. A robust national skills program will not only develop a class of entrepreneurs, but it will also multiply sub-sectors within the services sector like education, health, water, sanitation, housing and other quasi-government service providers.

From this point on, the government has to be focused on microeconomics and notably the common man. Such a process will automatically create a vibrant private sector. The first and second editions of the Growth & Transformation Plans (GTPs) focused overwhelmingly on the needs of the macroeconomic sector and in the process failed to take the fruits of applied resources to the common man.

This gave rise to monolithic state enterprises that soon burdened the economy with debt and mismanaged projects. Higher incomes in the hands of the masses will increase the tax base leading to fiscal sustainability. More importantly, the optimism generated by the coming of the new administration will be channeled into productive areas, lending support to the government in its effort to address economic ills.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 05,2018 [ VOL

19 , NO

971]

Viewpoints | Apr 15,2023

Viewpoints | Jan 05,2019

Commentaries | Apr 22,2022

Viewpoints | Dec 21,2019

Commentaries | Oct 16,2024

News Analysis | Jan 01,2022

Fortune News | Jul 29,2023

Commentaries | Apr 03,2021

Editorial | Apr 11,2020

Radar | Aug 26,2023

Photo Gallery | 180494 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170689 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161751 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137288 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Nov 2 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has scrapped the credit-growth ceiling that had s...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

The burgeoning data mining industry is struggling with mounting concerns following th...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Berhan Bank has chosen a different route in its pursuit of a new headquarters, opting for a transitional building instea...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Nib International Bank S.C. has found itself at the epicentre of a severe governance...