Editorial | Jan 18,2019

Dec 23 , 2023

By Peter Middlebrook, Amba Tadaa, and Eleni Armelinda Kubolli , Dawit Ayele

In the last two decades, Ethiopia underwent a metamorphosis under the stewardship of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) at its helm.

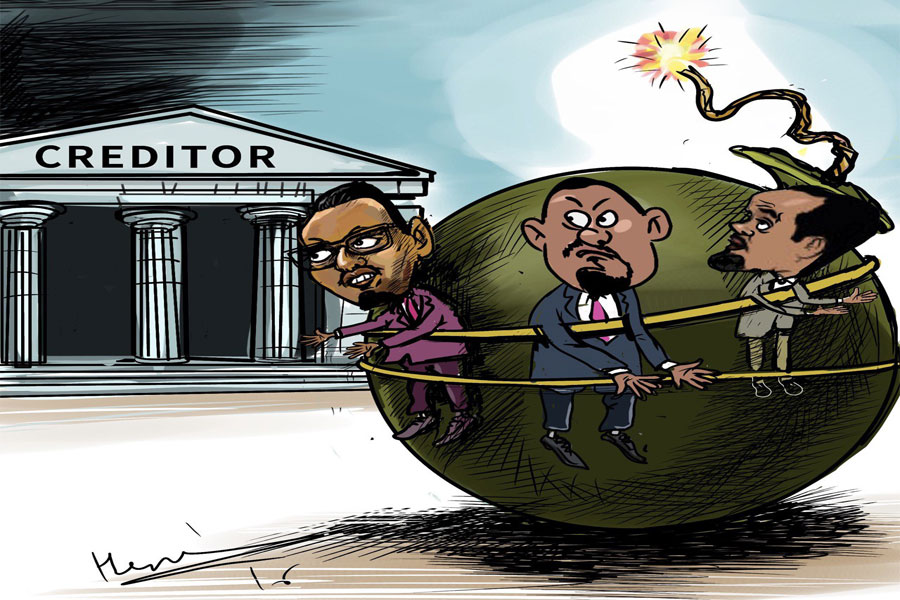

This was a period defined by a robust growth path, fueled by a state-led development model heavily reliant on external financing, including significant debt from China and grants from international development partners. However, the economic expansion during this era, while remarkable, was marred by uneven distribution and an economy that often ran too hot, sowing the seeds of internal strife within the EPRDF-led government.

The legacy of Meles Zenawi, the figurehead of that era, gradually diminished, leading to a seismic political shift that saw the TPLF’s influence wane and the ascent of Abiy Ahmed to power in 2018. The political upheaval dovetailed with the demise of the EPRDF’s order, precipitating a two-year civil war beginning in November 2020.

In parallel, Ethiopia has endured several adversities, including the COVID-19 pandemic, climatic stresses, global financial tightening, and inflation, particularly in food prices, culminating in a precarious macro-fiscal imbalance.

Faced with economic headwinds and the arduous task of servicing its debt, Ethiopia, under Abiy’s leadership, committed to structural reforms, signalling a shift from a state-led to a more liberal economic model. The shift has seen moves to liberalise national assets such as telecoms, banking, and logistics, along with efforts to establish domestic capital markets and deepen financial markets.

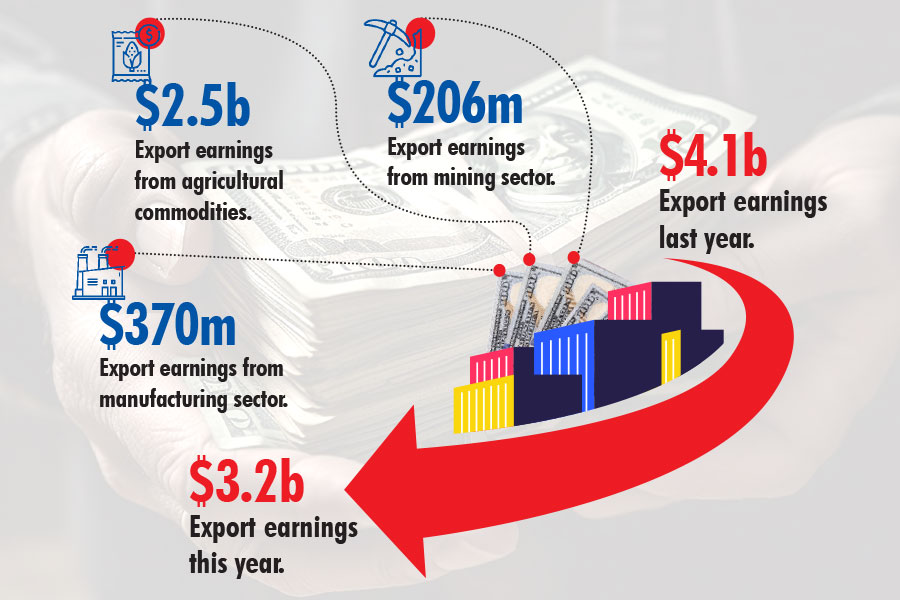

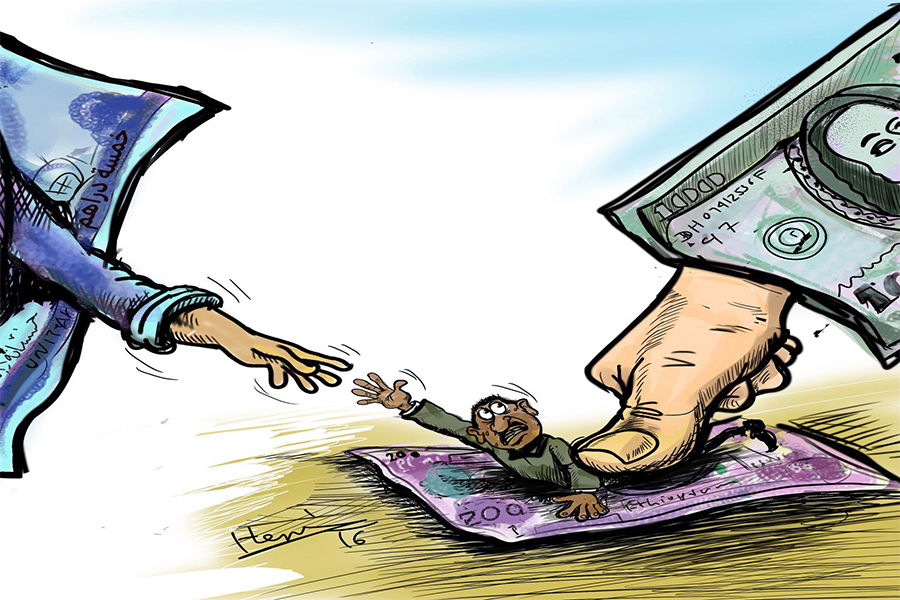

The federal government has also embarked on restructuring state-owned enterprises, steering them towards corporatisation and, in many cases, privatisation. Despite ongoing challenges like foreign currency shortages (which stifles investment), debt servicing (which reduces fiscal space), and revenue mobilisation, these reforms have already begun to recalibrate the balance between public and private capital; the state and the market.

Ethiopia’s reliance on short-term global borrowing and grants, coupled with the insufficient returns on infrastructure investments to service the construction debt, has led to sustainability concerns. The internal demand for capital remains high, yet liquidity issues persist, and the high cost of debt is a drag on current and future public investment. As Ethiopia braces for its Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda (HGER-II) launch in 2024, aimed at addressing macroeconomic vulnerabilities and unleashing the country’s economic potential, it finds itself at a crucial juncture. A new financing architecture and approach to sustainable development finance is now urgent.

The global economy’s post-COVID-19 trajectory, characterised by investments in green, frictionless, and automated (and paperless) economies, presents Ethiopia with a unique opportunity to leapfrog into the future (bouncing forward, not just bouncing back). However, the transition from three decades of state capitalism to a liberalised economy is fraught with challenges. The state has long been the economic linchpin, with large state-owned enterprises dominating the economy's commanding heights.

The systemic shift demands not just policy changes but a fundamental mindset overhaul. Key priorities include foreign exchange reforms, debt restructuring and a move towards more sustainable financing solutions, digitalisation, financial sector deepening, and digital tax collection system development. Financial sector liberalisation must be balanced with regulation to promote domestic capital market development and address the funding gap in retail and SME financing.

Enhancing export efforts and establishing a robust peace agenda are also critical.

The lessons from the transition of former Eastern European countries from state capitalism to market-based systems in the post-Soviet Union era are instructive. Many of these nations faced (and continue to face) significant challenges, including political economy constraints to establishing functioning market mechanisms and regulatory frameworks and transitioning from central planning to market-oriented policies. Corruption and nepotism are other issues.

Privatisation often leads to social and economic disruption, increasing unemployment and inequality. Inadequate legal systems, lack of entrepreneurship experience, and limited access to capital undermined the development of a competitive private sector.

With its limited capacities, Ethiopia must navigate these challenges while implementing one of the last liberalising reform agendas of the post-Soviet legacy. Given its projected population growth to 350 million by the end of the 21st Century, significant changes in agriculture, production, and urbanisation needed, alongside a focus on inclusive growth, are imperative. Failure to ensure inclusivity could exacerbate climate change impacts, internal tensions, migration, and displacement.

Ethiopia must commence a comprehensive, priority-driven, private-financing first transformation agenda to avoid such eventualities. Once lauded as a model for African economic reforms despite its outdated economic ideology, its leaders must now pivot towards the future, embracing a broad spectrum of modernising reforms. This requires a mindset shift towards resilience, deep digital transformation, planning scalable SMART cities with affordable solutions, deepening financial and capital markets, and consolidating peace and political settlements.

Much is at stake. As Ethiopia moves towards becoming a middle-income country by 2050, its economic stabilisation and growth are vital for the Horn of Africa’s peace and development. The country’s strategic geopolitical location and untapped economic opportunities position it uniquely to secure its future and contribute to the wider region’s stability and prosperity.

Ethiopia’s path to economic transformation is inextricably linked to its regional role and international relations. The Horn of Africa, a region historically fraught with instability and conflict, is now looking towards Ethiopia as an anchor of potential stability and economic growth. This crucial position should not simply be taken as a source of national pride, but a regional necessity, as its stability is integral to the Horn of Africa’s peace and prosperity from the Red Sea across the entire Nile Basin.

However, this journey is riddled with challenges, some unique to Ethiopia’s socio-political landscape. Its history and strategic location are assets, but they also bring a legacy of complex internal dynamics and external pressure.

For instance, the issue of access to sea routes, notably the Port of Asab, remains a contentious topic. Ethiopia’s landlocked status since Eritrea’s separation in 1991 has been a significant economic holdback. While calls to reclaim access to the coastline grow louder, the potential implications for regional geopolitics, particularly with Djibouti and Eritrea, are profound.

The Nile River, a lifeline for Ethiopia and its neighbours, particularly Egypt and Sudan, adds another layer of complexity. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a symbol of national pride and potential economic boon, has been a point of contention with downstream countries. Ethiopia’s actions on the Nile have implications far beyond its borders, impacting regional diplomacy and relationships with key international partners.

Ethiopia’s relationship with the Gulf States, particularly in trade and investment, is another critical dimension. The Gulf States have emerged as significant economic players in the Horn of Africa, with substantial investments and strategic interests in the region. Ethiopia’s ability to navigate this relationship while balancing its economic interests and regional dynamics will be crucial in shaping its future economic trajectory.

Domestically, the government faces the Herculean task of reforming and modernising its institutions. The shift from a centralised and state-driven economic model to a liberalised market economy requires not just policy changes but also a transformation in the role of state institutions. This involves streamlining governance, improving efficiency, and enhancing the delivery of public services. With the right policies, the right financing, international support, and a focus on sustainable and inclusive growth, Ethiopia stands poised to emerge as a resilient middle-income country, setting a precedent for economic transformation in the region.

Embracing the digital economy presents the most considerable challenge and an opportunity in this regard. Embracing digital transformation can lead to more efficient and transparent government services, improved financing inclusion and a tool to contract informal markets, but it requires significant investments in technology and human capital.

The Ethiopian diaspora's and youth's role in this transformation cannot be overstated. With its global connections and expertise, the diaspora can be a valuable asset in its economic reform journey. If properly harnessed through education and employment opportunities, Ethiopia's burgeoning youth population can drive economic growth and innovation. However, failing to engage these groups effectively could lead to a lost generation and squandered economic potential, potentially undermining a more optimal balance between public and private domains, allowing a new social contract to emerge more resilient to domestic shocks..

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 23,2023 [ VOL

24 , NO

1234]

Editorial | Jan 18,2019

Sunday with Eden | Jul 08,2023

Fortune News | Jul 01,2023

Editorial | Feb 16,2019

Editorial | Feb 24,2024

Editorial | Jul 27,2024

Viewpoints | Jul 01,2023

Commentaries | Dec 04,2020

Commentaries | Jul 08,2023

My Opinion | 131770 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128154 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126099 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123721 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...