Agenda | Apr 27,2025

Dec 4 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

For a while now, we have been used to thinking that we live in a dark time in history. The rise of illiberalism, extremism, and protectionism worldwide has served as the first signs of hard times to come for societies. In 2020, a global pandemic infected over a quarter of a billion people (those that have been reported), killed at least 5.2 million people and almost destroyed economies. In Ethiopia, we have had a civil war raging since last year, harming almost every facet of our lives and putting young generations' future at stake. Under such circumstances, cynicism is obviously on the rise.

Is this the twilight of human civilisation or, with global warming, even of the human species?

It is hard to stay optimistic in these times, but there are some reasons to do so. We are not the first generation to believe that the end is near – with the way social media algorithms work, the fear level has run riot. We are only presented with a challenge. If past generations managed to push through, there is no reason we cannot as well.

If anything, we are living in the age of simultaneous regression and unprecedented progress. Sure, we are amid an unwieldy pandemic, but scientists also developed a vaccine in a year. Global warming is on the rise but some of the world’s most capitalised firms are tech companies, including Tesla, an electric car company. Innovations in fintech, green technologies, AI and the space industry are noteworthy.

None of these even compare to the greatest weapon known to humankind: information. Admittedly, its use to the advantage of human wellbeing has been sparing. Most people, especially in Ethiopia, only use the internet to get political updates, post photos or get in touch with loved ones. The pre-internet age science fiction writers never imagined that we would have nearly every bit of knowledge and wisdom ever recorded at our fingertips, and even less, we would misuse it to such an extent.

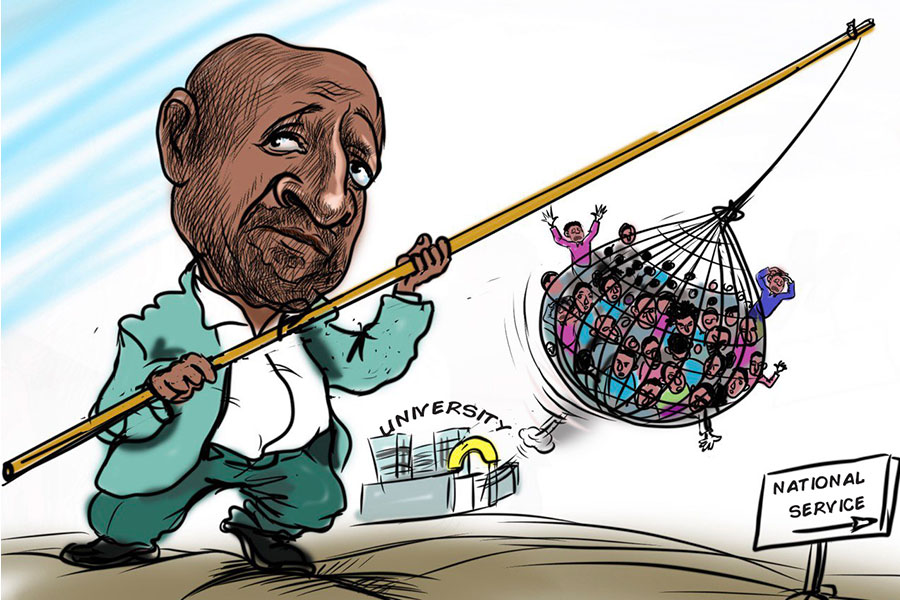

There is still hope that all of this information could be turned around and put to good use. This is through the democratisation and accessibility of education. Modern higher learning institutions have become profit-making companies that deny low-income households and countries the credentials necessary for entry into the job market and the knowledge base to thrive in our modern world. History will look back at them as one of the main challenges to progress for humanity.

And then there are the initiatives that give hope. It is one thing to have a wealth of information at one's fingertips, quite another to have it organised and make it accessible enough for learners. There are several efforts now to make the latter possible and imbue the youth from developing and low-income countries with the competitive advantage that has been privileged for the rich.

One of the unique learning platforms is Khan Academy. It does not cost a penny but it offers anyone with an internet connection colourful and surprisingly well put together lecture videos and quizzes on most subjects. It stays afloat through donations.

Others like Coursera and Udemy offer online basic-to-advanced college courses delivered by university professors. There are sometimes peer-reviewed assignments and discussion boards. These courses usually conclude with a certificate - fees can be waived for students without the means to pay.

Perhaps most promising is initiatives such as the University of the People, an aptly named US-accredited distance-learning institution. It is tuition-free so students are not expected to dole out tens of thousands of dollars. There are administrative fees, around 3,000 dollars, but there is financial aid even for this.

These efforts are necessary to democratise education across the world. The credentials of these institutions need to be recognised by more institutions and supported financially to provide education more accessibly. Billions of capable youth from low-income countries and households are locked out of higher education learning, perpetuating their poverty. If this is not addressed soon, there are even fewer reasons to be optimistic for the world.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 04,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1127]

Agenda | Apr 27,2025

Agenda | May 21,2022

Viewpoints | Sep 08,2024

Commentaries | Sep 18,2021

Agenda | Oct 03,2020

My Opinion | Feb 29,2020

Fortune News | Apr 19,2025

Commentaries | Apr 10,2021

Editorial | Apr 13, 2025

My Opinion | Sep 28,2024

My Opinion | 131768 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128151 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126097 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123719 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...