Fortune News | Aug 02,2025

Oct 1 , 2022

By Takatoshi Ito

When it was announced on September 13 that the consumer price index – a key measure of inflation – in the United States had increased more than expected in August, stock prices plunged and the US dollar appreciated sharply. Markets knew that this would spur the US Federal Reserve to announce another significant interest-rate hike. And that is exactly what happened. But the pain of monetary tightening is just beginning.

The Fed is not alone in raising interest rates. Soaring inflation – which has reached double digits in the European Union and the United Kingdom – has spurred the European Central Bank and the Bank of England to do the same, though many economists still accuse all three monetary authorities of being behind the curve.

Central banks in Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand also raised their policy rates by 25 basis points, and the Philippine central bank by 50 basis points, in August. Inflation stood at 7.9pc in Thailand, 6.3pc in the Philippines, 5.7pc in South Korea, and 4.7pc in Indonesia the same month.

One Asian economy that is not struggling with skyrocketing prices is China. With inflation running at 2.5pc, the central bank lowered its key interest rates last month. For China, the bigger challenge – and the main reason inflation has not spiked – is slumping economic growth, largely owing to the government’s zero-COVID policy. The slowdown is putting the overleveraged real-estate market under severe pressure.

Then there is Japan. After years of below-target inflation and even deflation, rising energy and food prices drove up core consumer inflation to 2.8pc in August – the fastest annual increase in eight years. But if one excludes fresh food and energy, the inflation rate was just 1.6pc in August, still below the two percent target. This explains why the Bank of Japan has yet to abandon negative interest rates (the overnight interbank rate remains at -0.1pc) or yield-curve control (capping the ten-year-bond rate at 0.25pc).

As the interest-rate differential between Japan and the US has increased, so has the yen-dollar exchange-rate swung sharply toward yen depreciation. With the yen having depreciated by almost 30pc in the last 12 months, the dollar exchange rate now stands at around 144 yen – a level last seen in 1998, during the Asian financial crisis.

Japan cannot maintain loose monetary policy forever. In fact, it should already be preparing for tightening. And interest-rate hikes are not the only way to pursue this objective. Central banks can also shrink their balance sheets, which have expanded significantly since the 2008 global financial crisis, when monetary authorities began purchasing huge amounts of long-term bonds under their quantitative easing (QE) programs. One means of achieving this is to let maturing bonds “roll off” balance sheets, rather than reinvesting them.

There is a risk here. Before a central bank has cleared its balance sheet of enough long-term bonds, rapidly rising interest rates will reduce the bonds’ mark-to-market value, even as the liability value remains unchanged. This could push a central bank into “technical insolvency,” with the mark-to-market liability value exceeding the mark-to-market asset value by more than the sum of capital and any buffer (accumulated retained earnings).

Japan may be particularly vulnerable on this front, given that it has long maintained a near-zero long-term interest rate. The average maturity of bonds on the asset side of the BOJ’s balance sheet is estimated to be 6.5 years, and their average return is extremely low. Yet, in reality, a technical insolvency would be a non-event. Unrealized losses are not a problem for a central bank that almost always holds bonds to maturity.

But central banks may confront another problem as they raise interest rates. A central bank earns its revenues from the interest on its assets (mainly government bills and bonds), and pays interest on remunerated reserves. The Fed started to pay interest on excess reserves in October 2008, owing to its balance-sheet expansion; the BOJ followed suit the next month.

This was not a problem at the time, because the interest paid on reserves is basically equal to the policy rate, which has been near zero, while interest rates for Treasury bills and bonds (or Japanese government bonds) have been positive, albeit trending downward. The interest differential between the asset and liability sides earned the central banks large profits – known as seigniorage – which are transferred to the government.

Large and rapid interest-rate hikes cut into these profits, as the interest paid on the liability side rises in line with policy rates, but most Treasuries have fixed rates. If policymakers are not careful, interest payments can exceed revenues and even consume any buffers the central bank may be holding. The result is so-called negative seigniorage, which requires the government to provide subsidies to the central bank – which could pose a political problem.

For the BOJ to avoid negative seigniorage, it must not rush the roll-off process. Moreover, it must allow the long-term interest rate to rise, by lifting the cap on ten-year bonds, before moving (slowly) to raise the policy rate. The question is whether economic and financial developments over the next few years will allow for this approach.

When central banks launched QE, the risks of technical insolvency and negative seigniorage were widely recognised. But governments stood behind monetary authorities. The Fed’s balance sheet was supposed to be backed by an implicit government guarantee. The UK government’s guarantee was more explicit. And Japan’s government allowed the BOJ to accumulate retained earnings.

As monetary tightening progresses, however, these commitments might be tested. Crucially, if negative seigniorage does arise, governments must refrain from turning it into a political issue.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 01,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1170]

Fortune News | Aug 02,2025

Viewpoints | Aug 14,2021

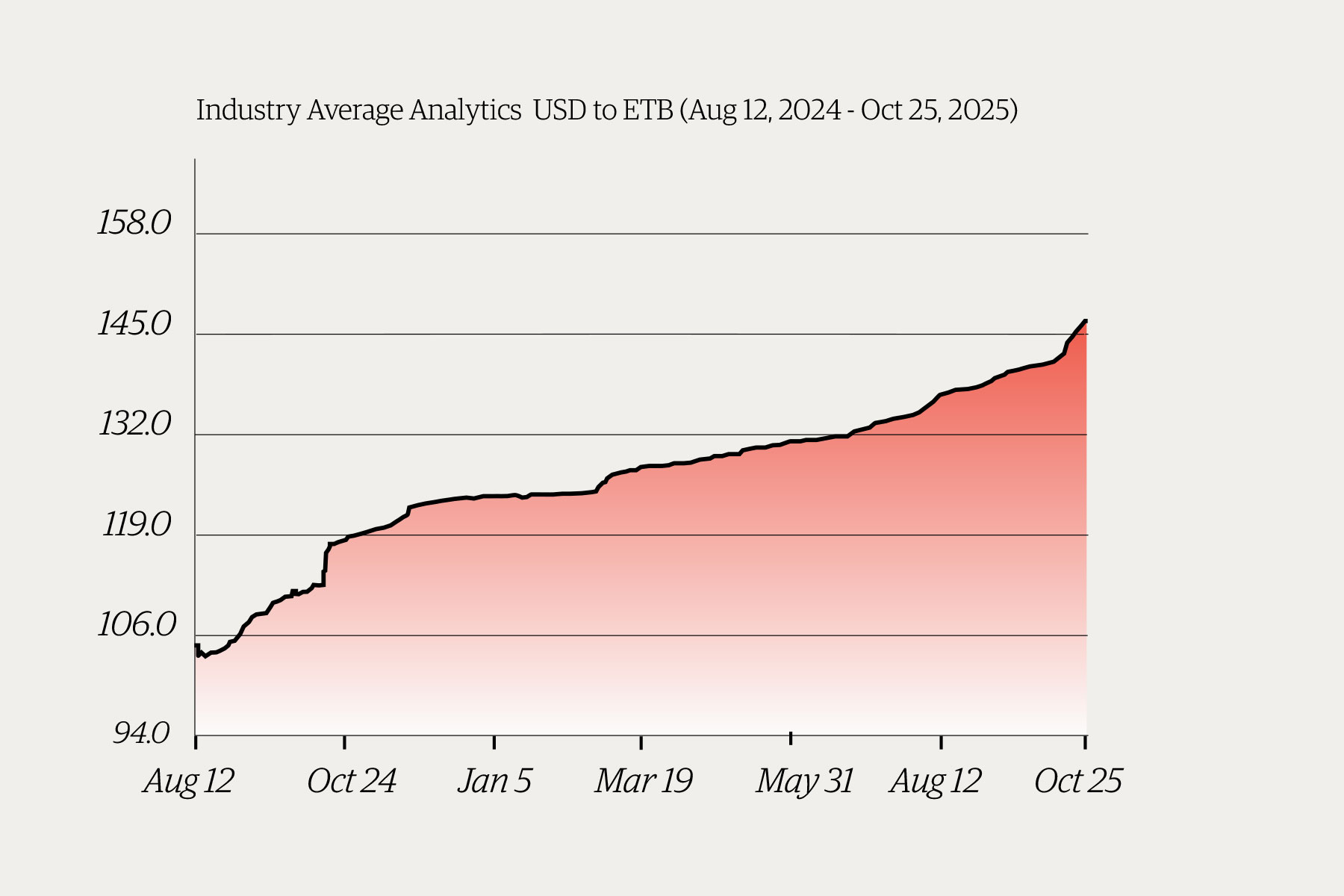

Money Market Watch | Oct 26,2025

Fortune News | Jun 29,2025

Fortune News | Jan 27,2024

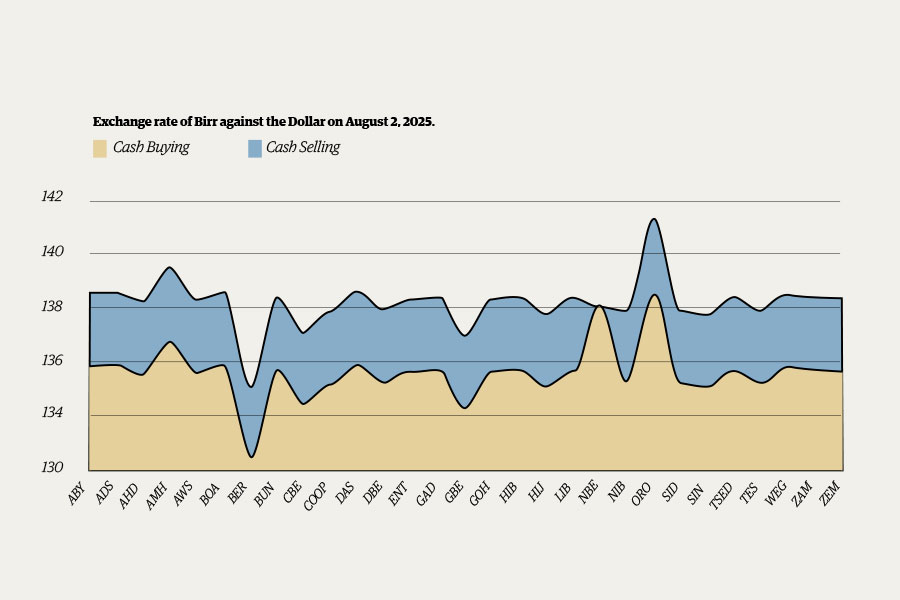

Money Market Watch | Aug 03,2025

Fortune News | May 31,2025

Viewpoints | Feb 26,2022

Radar | Jan 29,2022

Commentaries | Sep 18,2021

Photo Gallery | 179559 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169756 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 160687 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137190 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...