Editorial | Jul 13,2024

Mar 6 , 2021.

It was somewhat of a surprise when officials at the electoral board came out to announce a new polling date for the year; national elections are slated for June 5, 2021. With a war raging in Tigray Regional State, the political circumstances under which it would be held seemed a great deal more daunting than the COVID-19 pandemic that had led to a postponement last year. Besides, two of the main challengers active in Oromia Regional State – the Oromo Federalist Congress and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) – chose to keep their distance.

Needless to say, polling day is approaching and has progressed past the process that was made last year. This is, of course, barring the Tigray region, where an election is not included in the Board’s calendar. Since mid-February, campaigning has started and continues to occur five days before the electorate cast their votes.

Predictably, it is the political situation that has gained the most traction. Indeed, it should. Reports coming out of the Tigray region grow more worrisome and heart-wrenching by the day. It deserves all the attention it can get and more. Also concerning is the state of democratic institutions – from public media to the security apparatus – which were promised to be reformed over the past year. Major contending parties have stressed that their capacity to participate in the upcoming election has been severely constrained, calling into question its fairness and level playing field. The French would say "Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose" – the more things change, the more they stay the same.

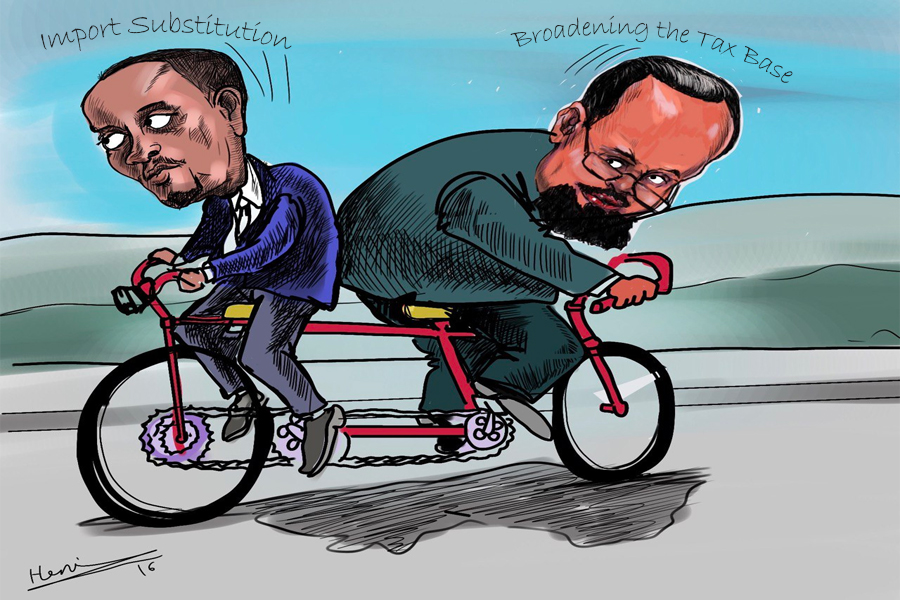

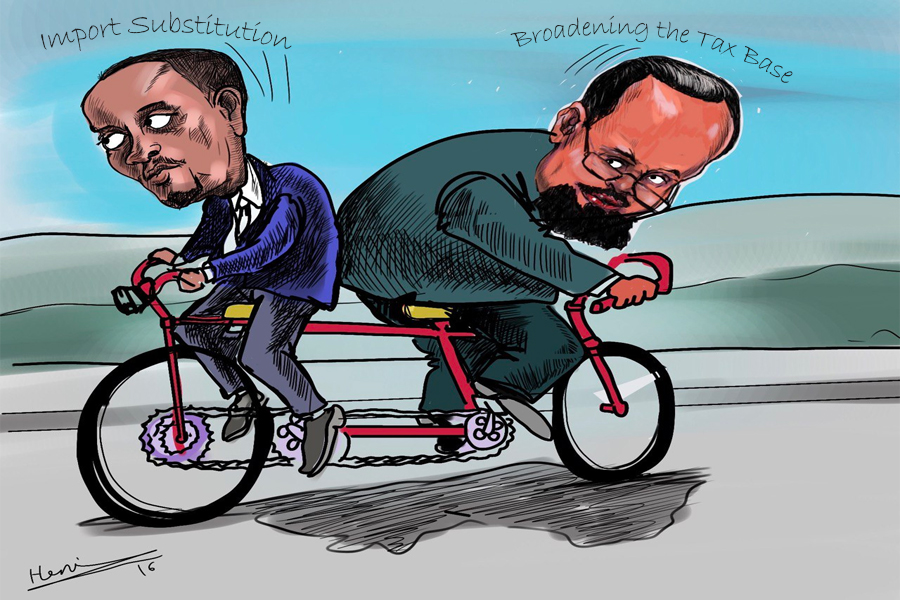

The consequences of the political turmoil have taken the wind out of discourse around the economy's direction. There appears to be no overriding ideology, a systemic body of concepts, that drives macroeconomic policymaking. There is no surprise to this, but neglecting the fundamental changes being made to Ethiopia’s underlying economic foundation should not be missed by contenders for state power. The electorate would – ideally – benefit from having clarity on what forces and interests are at play.

Much of this has to do with economic policies aggressively pushed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (PhD) administration. His rise to office brought a determination to liberalise sectors of the economy, privatise major state-owned enterprises, deregulate and cut subsidies. It was all in the name of curbing the state’s heavy hand in the economy and opening up to the private sector.

This is a sharp turn from the developmental economic model architected by the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. His administration inherited the command economy of the Dergue era, where production was under the strict supervision of the state. The EPRDF under Meles reigned in the state's overwhelming involvement through structural and institutional reforms. Hotels and factories were privatised, tariffs lowered and, most critically, the banking industry was opened to domestic players.

But the EPRDF stopped short of unleashing the private sector. Indeed, it remained suspicious of it. Land did not become private property while major strategic sectors such as telecom, logistics and airlines were limited to state monopolies. Goods and services from sugar, power, fuel and even rents on government-owned houses were subsidised. Despite flirting with the idea, Ethiopia also never joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO), although a working group was established as far back as 2003. The very idea of a capital market was dismissed as a speculative sport amounting to casino outfits.

Now, the times they are a-changin'. The current administration is implementing nothing less than a structural adjustment programme that sees subsidies being cut across the board. The currency is moving toward a market clearing rate, and a slew of liberalisation and privatisation policies that will re-order Ethiopia’s economy significantly are being carried out.

On its face, these are not bad policies if not untimely under the current political crisis. They amount to painful trade-offs but pushed by an administration without a popular electoral mandate. An economy under debt stress, galloping inflation, severe trade and balance of payments imbalance and a forex crunch need to be administered with tough treatments geared towards invigorating the private sector and limiting state spending and borrowing.

It is not only that these policies can be justified, but there is a case to be made to indicate that Ethiopia is not taking a turn to neoliberalism, as critics of the administration charge. Given a debilitating foreign currency shortage, tariffs on imports are not coming down any time soon. The government has also backed off privatising public companies such as Ethiopian Airlines, and the liberalisation of the telecom sector is likely to be gradual and chastened than expected.

But if its current priorities and focuses are any indication, it is clear what the programme of the administration would be in the foreseeable future, and this is a break away from the statist policies of the EPRDF-era. There is not much better proof of this than how the administration has chummed up to multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). They also seem to be responding in kind.

The Fund has praised the administration’s performance under a 2.9-billion-dollar programme that serves as a baseline for financial assistance to a balance of payments problem. The institution believed that the authorities are committed to further reforms and welcomed “Ethiopia’s request for debt treatment under the G20 Common Framework.”

Taken together, these developments point to major structural and even ideological reforms not seen since the Derguefell and the EPRDFites introduced developmentalism. Whatever the merits of the current administration’s economic agenda, it is a point that is barely discussed during a campaign season for much-anticipated elections.

As a result of a lack of being part of the debate, the public's awareness over this matter appears limited. When contenders for power talk about economic changes, it is often framed in the lens of nationalism. Take privatisation, especially of those in the Ethiopian Airlines league. Its partial privatisation was opposed largely out of nationalist sentiments; the push back is justified by "national pride" that the company should not be sold off to "foreigners".

The administration's unforthcoming attitude, especially about planned subsidies or currency depreciation, has helped the situation little. Sometimes, it resorts to blaming "economic sabotage" for the rise in the cost of living. There is no doubt there is a large and rather entrenched underground economy that challenges macroeconomic stability, but it also is hard to deny that the depreciation of the Birr and cuts to subsidies play a considerable part in rising prices.

This could mean a sacrifice the authorities may try and persuade the public to accept, promising improvement in due course. But what should be put to the ballot are the long-term consequences of the current administration’s reform agenda, as haphazard as it may look. Re-ordering the economy, if Marx is to be believed, redefines socio-political life. Whatever the political discipline, right-leaning economic policies lead to increases in wealth inequality, create a greater disparity in growth between rural and urban areas and give rise to monopolies and oligopolies with the power to corner markets and prices.

Private sector-led economies also experience more frequent booms and busts, while the economic elite gains the ability to influence social and political outcomes to its whims.

On the ballot is this new economic future to be realised if this administration gets a mandate or goes through the motions of an election to claim it has one. For the structural imbalances within the economy, they may be for the better. But what economic policies are preferable to the public, who pays the cost and how socio-political life will be reordered under this new economic system, needs to be included in the discourse.

With a campaign season that precedes an election the incumbent claims would be the most democratic, it is opportune time for opposition parties to underline that on the horizon is a new economic system endorsed by the Prosperity Party. Only with a public that gives political buy-in can the worst impacts of economic policy readjustments be tolerated.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 06,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1088]

Editorial | Jul 13,2024

Commentaries | May 13,2023

Commentaries | Oct 23,2021

Sunday with Eden | Jul 08,2023

Radar | Oct 20,2024

Viewpoints | Jan 05,2019

Radar | Feb 17,2024

Viewpoints | Sep 08,2024

Commentaries | Mar 30,2024

Radar | Jul 02,2022

My Opinion | 131770 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128154 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126099 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123721 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...