Agenda | Feb 22,2020

Apr 26 , 2025.

Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that “nothing is certain but death and taxes.” Yet, when taxes themselves threaten economic life, policymakers should reconsider their methods.

Ethiopia’s leaders seem keen to test this grim hypothesis, relentlessly increasing taxes on a dwindling pool of formal taxpayers. Rather than broadening the tax base, their heavy-handed approach risks strangling the economy and undermining their fiscal goals. They plan to mobilise no less than 1.5 trillion Br in federal taxes during the current fiscal year.

The current fiscal regime under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (PhD) administration represents the most aggressive tax move the country has seen in decades. Authorities argue that their approach is necessary because the tax-to-GDP ratio is worryingly low, around seven percent, far below the 15pc recommended by economic experts to sustain basic state spending in a low-income country. However, this diagnosis, although seemingly compelling on the surface, misses the deeper issue.

Historically, Ethiopia’s tax collection has always been weak. Despite multiple rounds of reform since the early 2000s, including introducing Value Added Tax (VAT) in 2003 and frequent adjustments to excise and income taxes, the tax-to-GDP ratio peaked at just 13pc in 2015 under the determined efforts of the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and former tax authority chief Melaku Fenta. Unfortunately, progress quickly reversed during Hailemariam Desalegn’s administration, plunging back to single-digit levels.

A narrow tax base, rampant evasion, and widespread non-compliance have consistently undermined tax mobilisation efforts.

Ethiopia’s population has more than doubled since 1991, growing from roughly 50 million to about 120 million today (although no one is in a position to state the actual figure). Yet, despite about 60pc being within the productive age range of 15 to 64 years, the vast majority — around 85pc — remain informally employed and outside the formal tax system. Rather than addressing this fundamental imbalance, the tax authorities continue to burden the already heavily taxed minority: formal employees and businesses.

Formal salaried workers face an extraordinary cumulative tax burden, up to 40pc of their income when direct and indirect taxes are combined. For instance, a middle-income earner making around 10,000 Br monthly loses about 20pc of their gross earnings to personal income taxes alone. Pension contributions shave off another seven percent, and VAT on essential purchases further shrink disposable income. Such steep rates typically exist in wealthier countries, not in low-income Ethiopia, where the per capita GDP is barely over 1,200 dollars annually.

Businesses suffer similarly. Corporate taxes stand at a hefty 30pc, worsened by numerous withholding taxes and cumbersome compliance rules. Even small enterprises that pass the modest turnover threshold of half a million Birr a year must enter the VAT system, enduring disproportionate bureaucratic costs compared to their modest revenues. This punitive tax environment and the arbitrariness of tax enforcers discourage businesses from expanding and push many to remain small, informal, and untaxed.

Economist Arthur Laffer famously illustrated that higher tax rates do not always translate into greater tax revenues. Past a certain point, excessive taxation reduces economic activity, discourages investments, and spurs tax evasion, ultimately shrinking overall tax collection. Ethiopia’s policymakers appear dangerously close to this tipping point.

Examples from other countries - rich and poor - demonstrate clearly how lower tax rates can boost revenues and stimulate economic vitality.

In the United States, Presidents John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan dramatically cut marginal tax rates, with Reagan famously reducing the top rate from 70pc to 28pc. Rather than collapsing revenues, the American treasury saw income tax receipts nearly double within a decade to almost 950 billion dollars by 1990. Economic growth surged, and employment soared.

Britain under Margaret Thatcher saw a similar story. Thatcher reduced the top marginal tax rate drastically, from 83pc in 1979 to 40pc by the late 1980s. Contrary to predictions of fiscal ruin, Britain’s economy grew robustly, compliance improved markedly, and tax revenues expanded, enabling a remarkable economic revival. Neighbouring Ireland experienced similar success. In the late 1980s, facing economic stagnation and high unemployment, its leaders simplified the tax system and slashed corporate tax rates to 12.5pc by 2000. This policy shift catapulted the Irish economy from Europe’s laggard to its fastest-growing country, doubling overall tax revenues as its broader tax base expanded rapidly.

Even Russia’s experience provides lessons. Vladimir Putin’s government replaced a complicated progressive income tax structure, very much like Ethiopia’s, with a straightforward 13pc flat rate in the early 2000s. Tax compliance immediately improved, revenues increased enormously, and Russia experienced robust economic growth and fiscal stability.

Ethiopian policymakers seem unaware of or unwilling to learn from these global lessons. Instead, they continue to impose higher taxes on a shrinking formal economic sector. Parliament’s recent move to introduce additional income taxes to fund emergency humanitarian needs, though seemingly noble, risks damaging taxpayers’ trust further and eroding compliance, paradoxically undermining broader revenue mobilisation goals.

The current approach reveals profound unfairness at its core.

Formal employees and registered businesses shoulder disproportionately high burdens, while vast economic sectors remain essentially untaxed. This inequity breeds resentment, discourages expansion in the formal sector, and keeps the tax base dangerously narrow. If the authorities genuinely seek sustainable revenue increases, they should abandon their punitive tax strategy in favour of a more balanced, fair, and compliance-friendly system.

Kenya, Ethiopia’s regional neighbour, provides a practical model for tax reform.

With broadly similar tax rates — 30pc corporate tax, 16pc VAT, and substantial excise duties — Kenya consistently achieves a tax-to-GDP ratio between 16pc and 18pc. Its relative success lies not in higher rates but in more effective tax administration, improved digital systems, stringent compliance mechanisms, and widespread taxpayer engagement. Kenya demonstrates that efficient tax collection depends on broad compliance and effective administration rather than punitive tax rates.

Bangladesh, by contrast, illustrates the consequences of ineffective tax administration coupled with punitive rates. Despite similar taxation structures, Bangladesh’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains below eight percent, showing how administrative dysfunction and low compliance severely restrict revenue mobilisation.

Ethiopia now faces a similar predicament of dysfunctions in its tax administration, a state of reality that presents a critical choice for its leaders.

Policymakers can persist in their current high-tax, low-compliance strategy, inevitably leading to fiscal stagnation and a worsening economic crisis. Alternatively, they can adopt a proven approach of lower tax burdens coupled with robust administrative reforms. Experience from other countries confirms that lower, simpler, and fairer taxes can boost compliance, stimulate investment, and sustainably increase overall revenues. Ethiopia’s leaders would do well to heed these global lessons and recognise that sometimes, lowering taxes is indeed the smartest investment a government can make.

For a heavily agrarian and low-income economy, modest tax rates combined with efficient and fair administration could yield substantial improvements in tax mobilisation. Reducing tax burdens, simplifying tax rules, and broadening the base through targeted administrative reforms is not only sound economic practice but also an existential necessity for Ethiopia. This approach would address immediate fiscal pressures, stimulate economic growth, encourage formal business activity, and restore taxpayers’ trust.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 26,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1304]

Agenda | Feb 22,2020

Fortune News | Feb 12,2022

Radar |

Agenda | Jan 05,2020

Viewpoints | Sep 07,2019

Photo Gallery | 178130 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168340 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159107 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137050 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

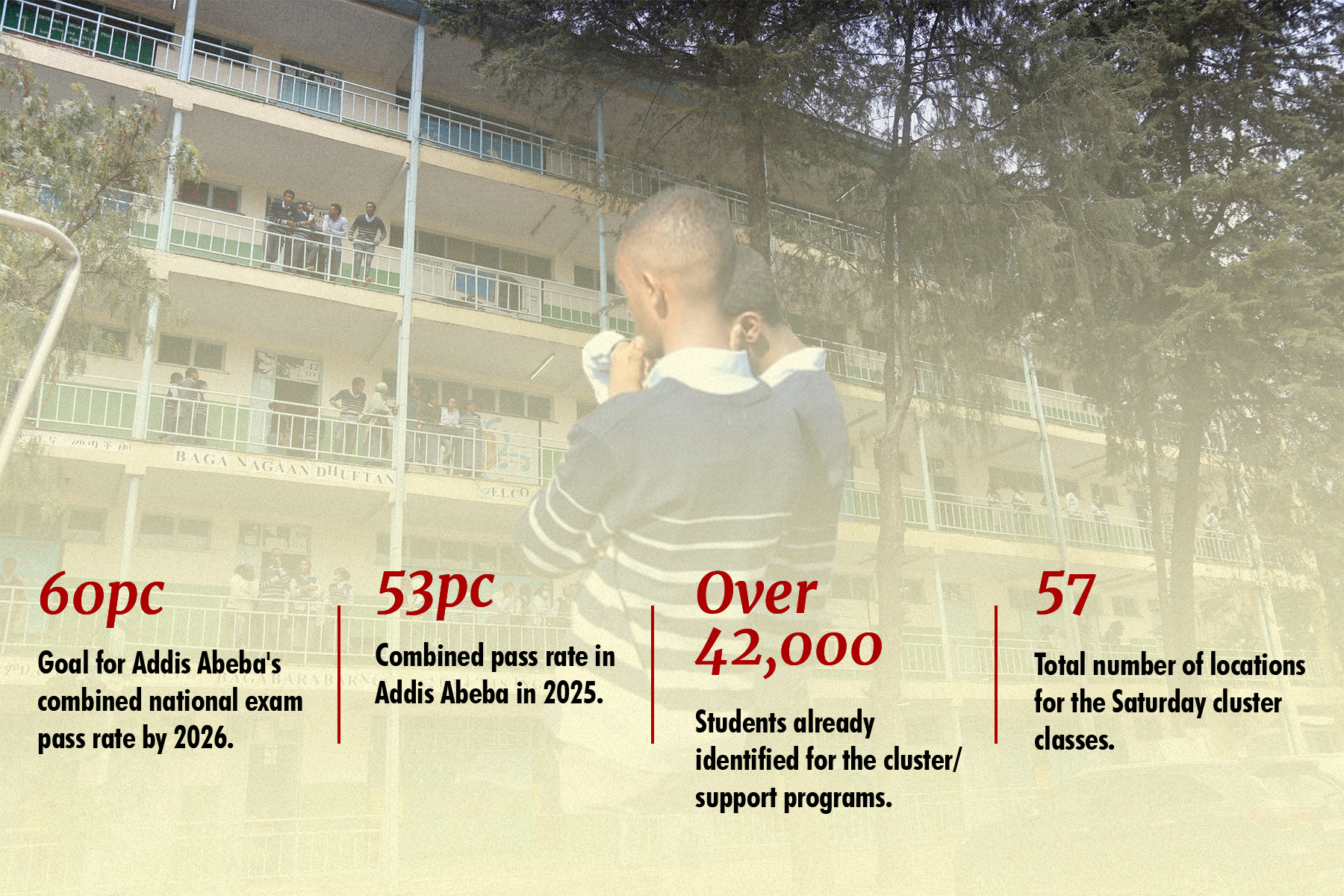

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 27 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...