Commentaries | Dec 23,2023

Sep 14 , 2024

By Mariana Mazzucato , Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Johan Rockström

The world confronts an unsustainable situation when it comes to water. Yet fixing the problem is not only within reach; it is also the low-hanging fruit in tackling climate change and generating jobs and growth.

The water crisis is plain to see. Year after year, in one region after another, record-high heat waves and droughts are followed by destructive storms and floods. Food systems are running dry and cities are sinking as we reach the limits of extracting water from the land. More than 1,000 children under the age of five die each day from illnesses caused by unsafe drinking water and a lack of sanitation, and hundreds of millions of women spend hours each day collecting and hauling water.

This is a human-made crisis, and it can and must be resolved through human interventions. But to achieve equity and sustainability everywhere, we will need new approaches to governing water and a wave of vastly higher investment, scaled-up innovation, and capacity-building. The costs of these moves are insignificant compared to the economic and humanitarian harms that will be inflicted by continued inaction.

The first step is to recognise that the problems we face are not merely local tragedies. A destabilised water cycle increasingly affects every corner of the world. Current approaches tend to deal with the water we can see – the "blue water" in our rivers, lakes, and aquifers – and assume that the water supply is stable year after year. But this is no longer true, as changes in land use, climate change, and a water cycle out of kilter are affecting rainfall patterns.

Too often, current thinking overlooks a critical freshwater resource, namely the "green water" in our soil, plants, and forests, which transpires and is recycled through the atmosphere. Green water generates around half the rainfall we receive on land, the very source of all our freshwater. In the same vein, countries are connected not only through flows of blue water (like rivers) but, more critically, through atmospheric flows of moisture. Green water needs to be better managed as a critical component of the global water cycle, urgently.

Most dangerously, disruptions to the water cycle are deeply intertwined with global warming and the decline of the world's biodiversity, with each reinforcing the other. A stable supply of green water in soil is crucial to sustaining the land-based natural systems that absorb 25pc to 30pc of the carbon dioxide emitted from fossil-fuel combustion.

This process represents one of the most significant natural subsidies to the global economy. Yet the loss of wetlands and soil moisture, together with deforestation, is depleting the planet's greatest carbon stores, with devastating consequences for the pace of global warming. Rising temperatures then trigger extreme heat waves and increase evaporative demand in the atmosphere, which severely dries landscapes and heightens the risk of wildfires.

Hence, the water crisis impacts virtually every one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and threatens people everywhere. Insufficient food for a growing world population, an accelerated spread of diseases, and increased forced migration and cross-border conflicts are just a few of the predictable outcomes.

Such a large-scale collective and systemic problem can be fixed only with concerted action in every country and through collaboration across boundaries and cultures. A shared understanding of the common good is crucial. Otherwise, what might look good for one country today could easily create problems for that same country tomorrow, as well as for others around the world.

Addressing the global water crisis requires more than ambition. It demands a mission-driven approach that integrates efforts across sectors, from managing local river basins to shaping multilateral cooperation. The success of these efforts hinges on tackling some of the most pressing water challenges, including launching a new Green Revolution in agriculture that reduces water use while boosting crop yields to meet the nutritional demands of a growing global population.

At the same time, conservation and restoration of natural habitats are critical to safeguarding vital green water resources.

Establishing a "circular" water economy is also essential. This would ensure that water is reused and recycled across industries, reducing waste and securing resources for future generations. Equally pressing is the need to guarantee that every vulnerable community has access to clean and safe water, as well as proper sanitation, by 2030.

Achieving these goals requires more than just policy shifts. The private and public sectors must align efforts and foster innovation. Effective governance is critical, and this means policymaking needs to become more collaborative, accountable, and inclusive. The voices of youth, women, marginalised communities, and Indigenous Peoples, who are on the frontlines of water conservation, must be central to these efforts.

While these water missions may seem ambitious, they are essential for addressing one of the world’s most urgent challenges. The key to success lies in reshaping how we govern water and building a framework that fosters innovation and cooperation at all levels.

The most fundamental policy shift lies in properly valuing water to reflect its scarcity and critical role in sustaining the natural ecosystems that every society depends on. We must cease the underpricing of water across the economy and the harmful agricultural subsidies that drive unsustainable usage and degrade the land. Rechanneling those funds toward promoting water-saving solutions and providing targeted support for the poor and vulnerable would go a long way.

To fix chronic underinvestment in water, we must reprioritise water infrastructure in public finance, where it is oddly neglected in most countries. Policymakers can draw on best practices in public-private partnerships to provide fair incentives for long-term commitments, while serving the interests of the public, especially underserved communities.

Given the collective nature of the water challenge, we must ensure larger and more reliable flows of finance to help low- and lower-middle-income countries invest in water resilience. Multilateral development banks, development finance institutions, and public development banks will need to work closely with governments to support national water missions that reflect local needs and ecological conditions. International trade agreements also offer potential levers to promote efficient water use, because they can help to ensure that the "virtual water" embedded in traded goods does not aggravate scarcity in water-stressed regions.

As we are doing for emissions, we must compile high-integrity data on corporate water footprints and create frameworks for water-use disclosure. We must also develop systems for valuing water as part of natural capital. Putting a price on this critical resource could deliver significant dividends for countries over time. We must shape markets across our economies – from agriculture and mining to energy and semiconductors – so that they become radically more efficient, equitable, and sustainable in their water use.

The 2023 preliminary report of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water set out the case for pursuing fundamental change in how the world manages water. Our final report this October will show how we can do so through transformative, collective action.

We are only in 2024. If we do not address these problems head-on, wildfires, floods, and other water- and climate-driven extreme events will only get more intense and deadly in the years to come. Advancing the water security agenda may seem more difficult amid growing geopolitical tensions, but it presents an opportunity to prove that collaboration can benefit all countries and enable a just and livable future for all.

We cannot shrink from this challenge.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 14,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1272]

Commentaries | Dec 23,2023

Radar |

Sunday with Eden | Dec 14,2024

Covid-19 | Apr 01,2020

Fortune News | Apr 30,2022

Commentaries | Apr 26,2025

Viewpoints | Jul 20,2024

Fortune News | Apr 03,2023

Radar | Aug 24,2019

Commentaries | Jun 13,2020

Photo Gallery | 175312 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165536 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155858 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136802 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

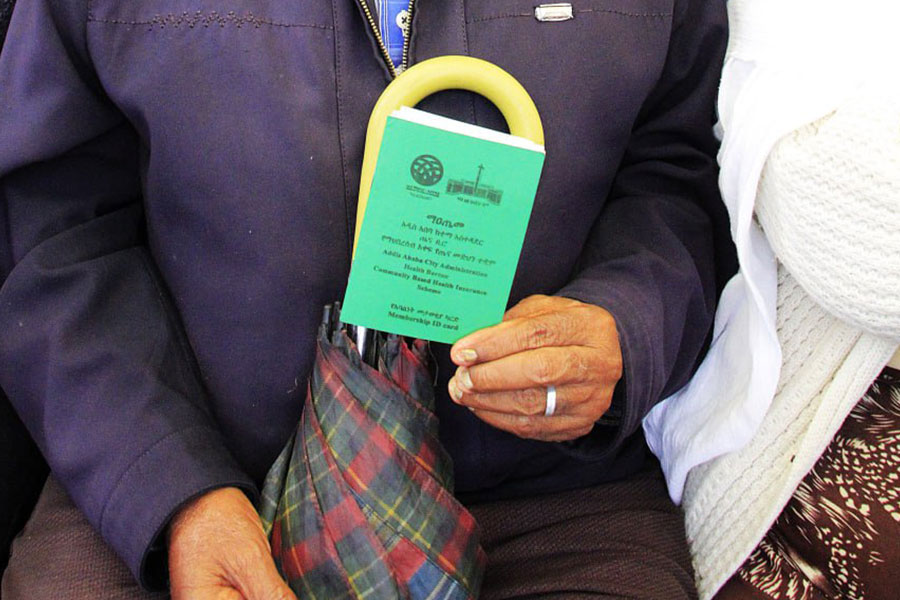

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...