Aug 16 , 2020.

It is not uncommon for economic policies to go under the radar. Still, neither is it normal for a policy agenda as critical as the Homegrown Economic Reform to have disappeared from discussions.

Where is it now? One wonders when seeing the prominence in its place of the 10-Year Perspective Development Plan, a strategic document for the next decade that government officials are currently raving about. Carrying the slogan, “Ethiopia: An African Beacon of Prosperity,” and visually presented against a green background, it has been under discussion over the past month.

Heads of federal government agencies - from the Ministry of Culture & Tourism to the Civil Service Commission and the Peace Ministry - have participated in sessions where their 10-year plans have been discussed. Senior envoys have been called home to spend no less than 10 days to brainstorm the foreign affairs agenda for the next decade.

The compatibility or overwriting state of this plan - authored under the stewardship of Fitsum Assefa (PhD) - with the Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda architected under Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) was never made clear. The ambiguity could be by design, a defining characteristic of the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD).

Strikingly, complete policy documents pertaining to development strategies have yet to be made public, in both cases, despite constant remonstrations from interested parties. The Planning & Development Commission has not bothered to make public documents detailing the specifics of the Plan. This should not have been the case even if these documents are currently in the drafting process.

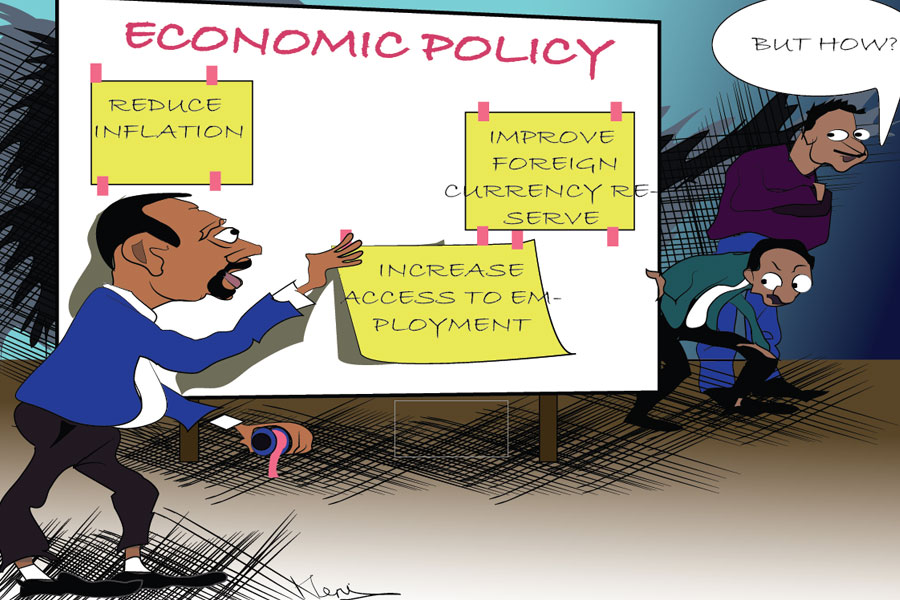

But there is no shortage of footage of the discussions, and economic targets have been presented in their generality. Leisurely. “Quality” economic development, ensuring private sector-led growth, realising competitiveness, institutional transformation, improving inclusivity and building a “green” economy, as Fitsum stated, are the primary areas of focus.

She could not have been vaguer, or harder to disagree with. Except for the commitment to enhance the role of the private sector in the economy, the rest are broad strokes that should be the targets of any economic management under any circumstance. The devil is in the details. But as things stand now, the devil has been left to the imagination.

The presentations of the targets of the Plan up to this point are interesting in their similarities with the successive editions of the Growth & Transformation Plan (GTP), especially in the pace of development that is intended. It plans for an annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of around 10pc on average for the next decade and the reduction of the population under absolute poverty to seven percent.

It also envisages the creation of nearly 1.4 million jobs every year and attaining universal access to clean water and power by 2030. Improving infrastructure in roads, railways, irrigation systems and ICT has been emphasised, while 4.4 million houses are planned to be built within this period. These are all numbers betraying experience of over 10 years.

The Plan does mention the private sector more times than the GTPs did. The government’s role in the next decade would be to improve infrastructure, drafting and enforcement of policies and laws and, when it has to, investing in parts of the economy the private sector is not willing to engage in. The implication here seems to be that job creation would be the forte of the private sector.

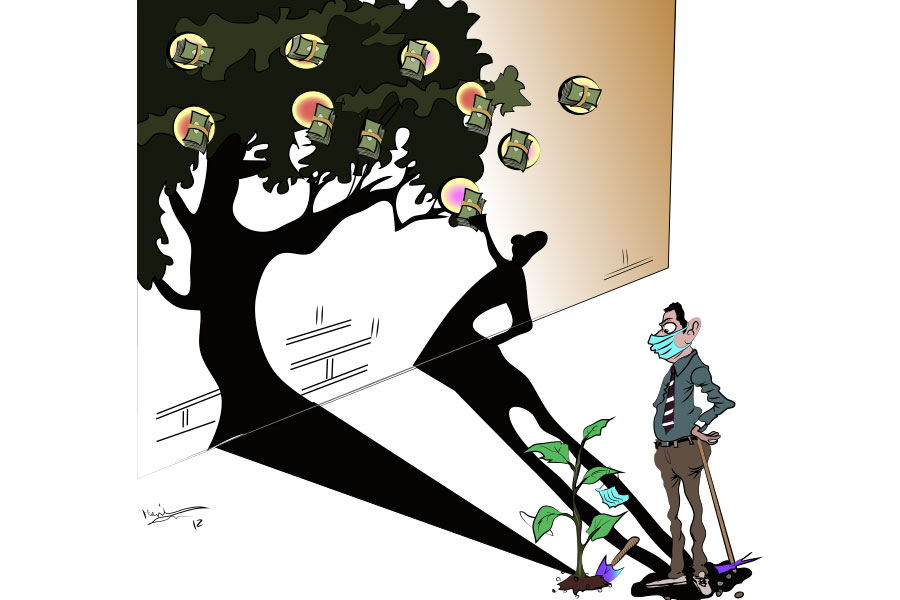

In its broad strokes, the Commission is targeting the best of both worlds. There evidently is a commitment to maintaining the rapid growth in GDP of Ethiopia, which was a result of large-scale public infrastructure spending but with an emphasis on rolling back the state’s involvement in the economy. It aims to improve access to education and health services while also raising the quality of their deliveries. It intends to secure private sector-led growth while ensuring an inclusive and just distribution of wealth.

In so far as economic policies are attempts to devise the possible means toward achieving socioeconomic needs, priorities could stand in contrast to each other. It is, for instance, impractical to prime economic efficiency while also attempting to redistribute wealth to narrow the gap in income inequitably. At least in the short term, the latter has to be sacrificed for the former.

It is not clear what the strategic priorities are. There is no acknowledgement of the compromises to be made in the type of ambitious growth that is demanded or clarity in the strategy that is to be followed. Market orientation, state intervention, import-substitution and export-led planning all seem to be hinted at and considered without an overriding guiding philosophy being forwarded or explaining how these divergent strategies could be harmonised.

This partly stems from lack of a proper assessment of the reform efforts of the past two years. Early in the life of this administration, a reorientation toward private sector-led growth was proposed. Considering the state of the economy, from rising inflation to a debilitating foreign currency shortage, Ethiopia did seem overdue for tweaking of its economic priorities. It was most glaring in the management of fiscal policy. Before long, the economy found itself on a path of liberalisation and privatisation, as well as contractionary fiscal and monetary policies that seemed imminent.

The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic threw these plans into a tailspin, and parliament recently passed one of the government’s most expansive budgets. It was what the economy demanded; but, it has not been clear how such aberrations and unexpected turns in policy were to fit in the administration’s economic philosophy. That is, if there is one.

Worse yet, it is not clear how it will inform decision-making going forward.

There are indeed developments that give some hope. The sectoral 10-year plans, currently undergoing revisions and amendments, do appear to be giving credit to the GTPs while also trying to understand their shortcomings. The previous two years of reform efforts are also part of these discussions, though it is not yet clear what assessments of it are, while other countries' experiences are also being considered.

The various discussions being held by different agencies, open and easily accessible, will also help identify pain points. If taken sincerely, they could help develop a bottom-up path to development.

However, there needs to be a guiding principle underlying these strategies. Principal considerations of socio-political circumstances need to be weighed with calls for economic efficiency and competitiveness. The structural failures that have underpinned imbalances in external trade and foreign currency shortage for such a long time need to be measured against the fiscal interventions that are utilised whenever the going gets tougher than usual. Most critically perhaps, the urgency to move away from the state’s heavy hand in the economy needs to be examined from the perspective of a private sector that will not be as good a replacement in attaining rapid growth.

Without answering these questions, the end result will be a mish mash of priorities that will make Ethiopia's ambition to become an African “beacon of prosperity” quite complex.Tas con

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 16,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1059]

Agenda | Jul 27,2019

Viewpoints | Jul 01,2023

Radar | Oct 23,2023

Editorial | Feb 24,2024

Fortune News | Jan 03,2025

Editorial | Jan 26,2019

Editorial | Aug 08,2020

Exclusive Interviews | Mar 04,2023

Viewpoints | May 04,2019

Commentaries | Sep 08,2024

My Opinion | 131658 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128022 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125985 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123609 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...