Life Matters | Nov 27,2021

Mar 16 , 2019.

The first newspaper ever published in Amharic, also the first ever in an African language, was issued in Addis Abeba. Although a progressive move at that time, it was not far removed from what defines the character of the nation’s media landscape today. Ae’mero, literally translated to “mind”, was a Saturday weekly that began running in 1901 with the not-so-subtle purpose of lionising the ruling class.

One edition had on its front page a poem eulogising Emperor Menelik II, a modernising statesman for his era. The poem was overtly partisan but made sense considering the political context of the time. In a period where family heritage was crucial in determining who reigns with absolute power, a non-conformist publication would have no chance of existence.

Over a century since that edition, the media industry that Ae’meropioneered has not veered too far from its essential roots. There may not be media organisations endorsing indefinite political rules, but many continue to fail to separate their editorial content from the worldview propagated by their owners, financiers or political sponsors. They remain partisan, unprofessional and instruments to a political order that they either want to maintain or substitute.

This is despite the significant political transitions that took place in the mid-1970s and early 1990s. There was in each case a consensus that an overhaul of the media landscape would be a crucial ingredient to the democratisation of the nation, an aspiration that was never realised. There are parallels to the three years of protests that culminated in a change of administration in the federal government and a call for EPRDF-led government to liberalise the political space.

Not surprisingly, fingers were pointed at the media landscape that operated in fear and under the shadow of anti-terrorist legislation that was used to charge and jail bloggers and journalists. That is one of the critical issues raised in demanding that the media be set “free.”

The media should be transformed to such a level that it can hold the state accountable when necessary. The thinking was that if the authoritarian government reforms laws that are constraining free public expressions of opinions, and content can be aired without fear of state retribution, then the ground for an independent and professional media would have been laid.

The thinking went that it would only be a matter of time before competition weeds out the riffraff and the public selects media houses that commit themselves to professionalism. The feedback loop would take care of the rest encouraging the media industry as a whole to strive for best practices, integrity and credibility in the eyes of the public.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) deserves credit for being able to stand for an open media landscape. Newspapers and magazines, at least in number, have mushroomed as have private broadcasters. The private media has been aggressive and assertive in content production. Dissident media houses designated before as “instruments of subversive forces” are now operating freely inside Ethiopia and the anti-terrorism and media laws are undergoing revisions. Judging by the presentation the working group on media law reforms held last week in Elilly Hotel, things are going reasonably well, a cause for optimism.

This is no small feat for an administration governing under close international and domestic scrutiny.

However, a “free media” does not in itself equate to a professional and independent one, a matter that has not been well understood by practitioners in the industry. Many are failing to note that the prevailing problems in the current media arise out of misconceptions of its duties and its relations with power. But, this is not to say that difficulties the industry faces in the legal and financial spheres are non-existent.

Indeed, the industry is faced with a lack of capital, skilled human resources, relevant education and training as well as a bureaucracy that is not used to close examinations. The prescribed solutions for these though merely address the problems but do not test the validity of the “progressive” nature of the industry. Because progressivism cannot be indefinitely secured, it has to be nurtured continuously.

An unprecedented advance in digital technology has meant revolutionary ways of communications, which unfortunately rewards misinformation and sectarianism than balance, depth and insight. It is another battle the media industry has to fight to protect the values and principles it is bound to.

The lack of values of professionalism and independence, acutely absent in the Ethiopian media landscape, is the primary reason why the nation’s media industry never acquired credibility. It is a battle that has to be fought and won.

The time for that battle is now, given that a relapse into old policies where the media functions merely as an instrument of the state, will be especially counterproductive to the ongoing political reforms.

Many of the media houses that have come to be influential in present-day Ethiopia are grounded in their view that Ethiopia is a “civilized state”. This is not a far cry from the Dergue’snationalist rhetoric and EPRDF’s developmentally-inclined media landscape. There is also another brand of media whose worldview is informed by the notion that Ethiopia is in the making of a “nation-state”, thus needs to be deconstructed and reconstructed.

The colours may be different, but they are all wearing the same T-shirts. In all cases, the media is valued for its instrumentalist use.

It is not regulations or budgetary supports that can address these problems. Neither could the kind of botched up engagement the Prime Minister was engaged in with media leaders last Sunday at UNECA.

It should start with the willingness of the media industry itself to redefine its purpose in society.

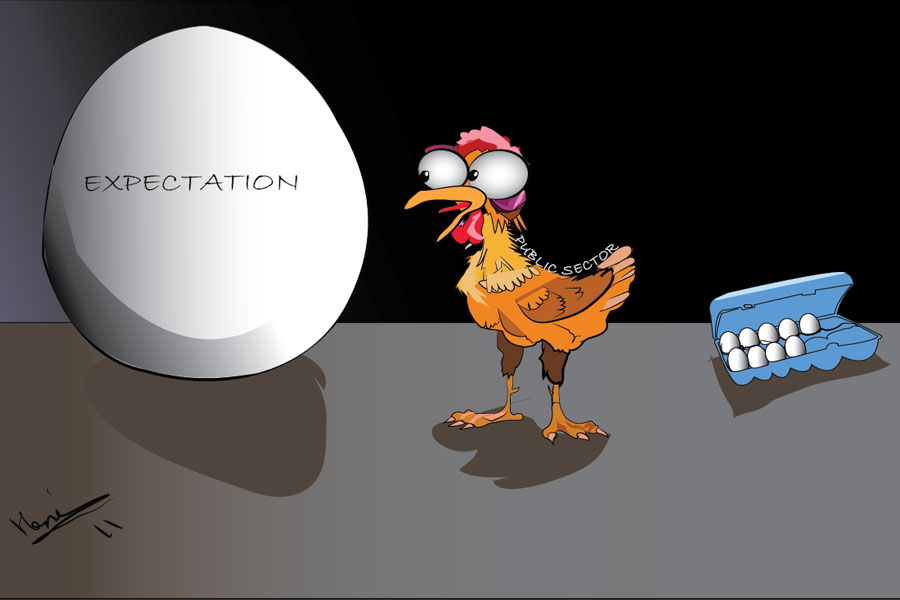

This begins with the state media, which has the farthest reach and commands better resources. Despite promises by this administration to allow the public media to be autonomous, it remains a tool for the incumbent and the political elite both on federal and regional levels.

If publically-funded media is willing to skirt professionalism and accountability, then there is hardly any reason to expect the private media to behave differently.

The opposition parties are bound to see it as a political tactic to reinforce their worldviews. The next step is a similar measure to counter it. Therein will be lost platforms where discourse can be reasonable, modest, rational, meaningful and, yes, civil.

Abiy`s administration role should not be to ban or penalise instrumentalists and adversarial camps because they have the right to exist. They also serve as a valuable voice for those on the fringe or even the marginalised. They are better left to their own fate than censure or outlaw them.

Nonetheless, the administration should issue a media policy where it uses various tools of positive support to encourage those in the media industry who aspire to be institutionalized, professional and ethical. Establishing institutional relationships and engagements between the industry and government institutions through a media council is another move in need of serious consideration. Through the combined use of a progressive media policy and a council, although the council has yet to be established, Abiy`s administration can and should support credible, accountable and responsible media players that define the industry.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 16,2019 [ VOL

19 , NO

985]

Life Matters | Nov 27,2021

Sunday with Eden | Apr 17,2021

Commentaries | May 25,2019

Fortune News | Jun 11,2022

Editorial | Dec 19,2018

Life Matters | Aug 29,2020

Commentaries | Nov 04,2023

My Opinion | Oct 09,2021

Fortune News | Jun 18,2022

Viewpoints | Dec 26,2020

Photo Gallery | 174759 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164981 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155222 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136724 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...