Apr 17 , 2020

By Lea Mehari

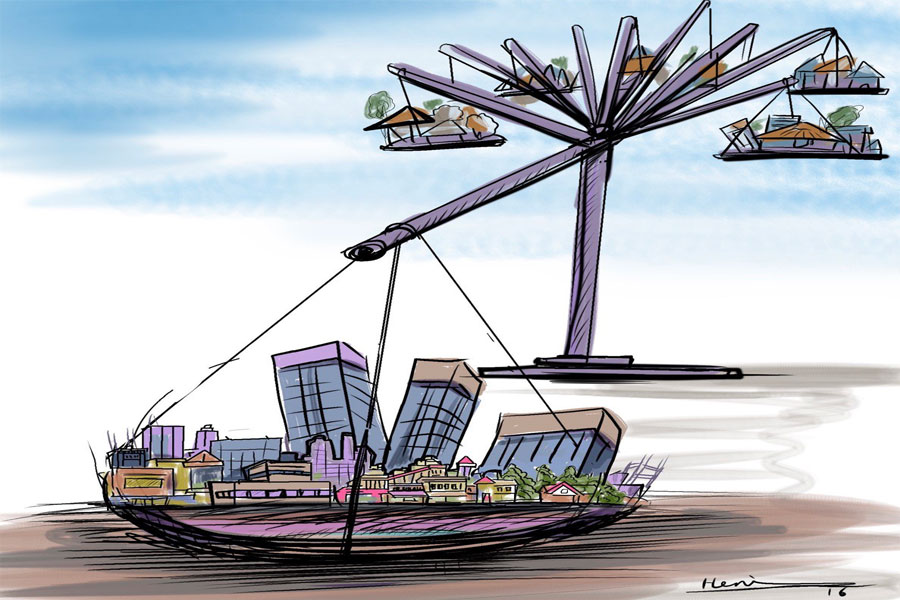

Thanks to globalisation, the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing nations has shown a marked increase. Many of these countries are persuaded that such investment will spearhead their economic development. The investors come with foreign currency, skills and networks. They create employment opportunities and share the risks of national development in return for some amount of profit.

What is not to like?

Many developing countries thus undertake economic and political reforms in order to improve the investment climate and increase the inflow of FDI. Ever since the early 1990s, when the country started to come out of its experimentation with a command economy, Ethiopia has been taking various measures to encourage the private sector.

To increase the inflow of FDI, Ethiopia has enacted various investment proclamations and regulations over the past decades. One such proclamation, passed earlier this year, provides attractive incentives for foreign investors, including the ownership of immovable property that is connected with the investment.

One of the selling points the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC) uses to attract FDI is the availability of land for investment. Investors can rent or lease land for up to 90 years. Across the country there are millions of hectares suitable for investment, and according to the EIC at least three million hectares have already been made available.

Land is public property in Ethiopia and cannot be sold between private owners. However, it can be transferred temporarily to private investors. The federal government has the power to enact laws necessary for the utilisation of the land, while the regional governments are in charge of its administration.

In 2005, the federal government enacted a proclamation that allows investors to lease or rent land from farmers and pastoral communities. The law states that the administration of the leases or rent agreements can be governed by the regional governments.

But there are still major problems caused by the lack of uniformity between states. The rules differ from one region to another in terms of the size of land allowed for lease or the duration of the leasehold.

There are also regional laws that deviate from the federal law, which provides that lease or rent agreements should not displace peasants or pastoralists. There have been instances in some regions where farmers have rented out the entirety of their land.

As it currently stands, there are no uniform guidelines or procedures for the transfer of land to investors, especially in the regional states. There are also no standard procedures for the assignment of rent prices or rules governing how the land can be used. The lack of standard guidelines has resulted in the arbitrary distribution of land for investment purposes, opening investment to unfair competition.

The EIC is mandated with facilitating land requests from investors. The Commission goes further, describing its mandate as “hand-holding and supporting the investor during the acquisition of land and utilities.”

But as land is not administered by the EIC, it cannot by itself allocate the land to the investors, creating an additional layer of bureaucracy that investors have to pass through to get the land. Also, provision of land leases can be denied for trivial reasons by local governments.

The only true power of the federal and regional investment commission and bureaus is issuing investment permits and giving different investment incentives. But land is administered either by the rural land administration or by the land development and management bureaus.

There is a reason for this, and it is understandable. Land, in Ethiopia, is considered to have worth beyond economic value. It has cultural and spiritual utility as well, and thus has never been left to purely economic considerations. Power when it comes to administering and allocating land for lease thus has not fallen entirely to economic institutions.

The unintended consequence of this has been that finding land to use for FDI has become a burdensome task for investors, the EIC and regional investment bureaus.

But it is still possible to create a system where investors can access land without sacrificing the non-economic value attached to it. This can be addressed by reforming the vague land utilisation and administration laws of the federal and regional states and introducing standards that apply across the country.

Uniformity and clarity are critical when it comes to the laws and the practice of land administration in Ethiopia if we want to attract more FDI and enhance economic growth.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 17,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1042]

Fortune News | Feb 29,2020

Radar | Nov 16,2019

Fortune News | Apr 06,2024

Radar | Jan 11,2020

Editorial | Dec 23,2023

Fortune News | Mar 25,2023

My Opinion | Nov 23,2024

Fortune News | Jun 13,2025

Fortune News | Feb 11,2023

Editorial | Sep 28,2024

My Opinion | 131674 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128040 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126002 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123625 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...