Editorial | Nov 11,2023

Jan 7 , 2022.

There has not been much research to put a number on high costs wars inflict on African economies. But a report by Oxfam in the late 2000s changed this. In the quarter of a century since 1990, 284 billion dollars have been wasted by African countries in the pursuit of wars. This includes Ethiopia and Eritrea, which fought a two-year, largely needless, conflict that claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people.

The report reads that the sum is comparable to the global aid in the same period. The annual average cost of wars, civil wars, and insurgencies to countries in Africa was estimated at 18 billion dollars, almost twice the size of Ethiopia`s annual budget. Infrastructure is destroyed and supply chains cut, while resources are diverted from productive investments towards buying weapons, spendings on medical care for the injured and support for displaced civilians. On average, a conflict shrinks an African country’s economy by 15pc.

It has not been any different for Ethiopia. Over 100 billion Br was spent due to the war in eight months since November 2020. Banks` non-performing loans are ballooning. Direct advances by the central bank to the federal government has also risen by nearly 170pc in the previous year, with “law enforcement” and the COVID-19 cited as causes. There is little reason to expect these costs not to continue this year. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed`s (PhD) administration has asked Parliament for 122 billion Br more money than the federal budget approved for this year.

Unadjusted for depreciation of the Birr, the federal government had already committed the highest budget ever.

Financing this budget remains tricky. External loans and grants have almost dried up due to displeasure by donors over the war. So were foreign direct investments not as forthcoming to a country mired in militarised conflict. Proceeds from exports, services and remittances are insufficient to cover the budget deficit. In an attempt not to bloat direct advances from the central bank to fund the budget - though this will not be entirely avoidable - the administration is going after subsidies. The most recent victims of this are wheat and fuel. The latter are immediately perceptible to the public. It will not be without a political cost for the Prosperitarians.

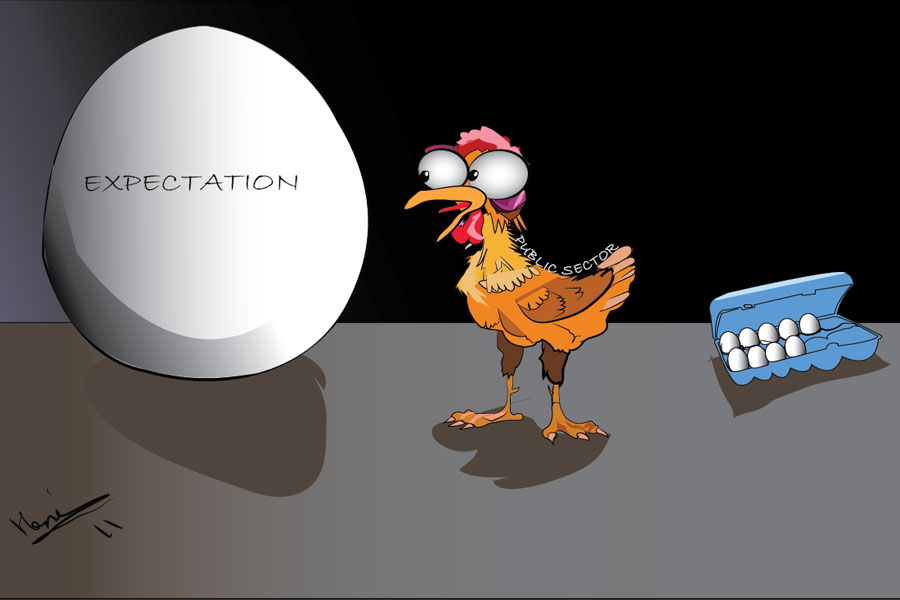

Granted, the administration did have intentions to phase out subsidies long before the war. A much more pro-private sector economic policy has sought to reduce the state’s heavy-handed involvement in the economy. Subsidies in electric power and sugar were long gone. The Federal Housing Corporation’s raising of rents based on market dictates was in itself a type of subsidy reduction, so to say.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic and the civil war, the case for phasing out subsidies was rational. It may not be fair to blame the current administration for such policy decisions with painful consequences. Successive regimes were passing the buck. They knew that it was not sustainable to continue subsidising a growing population and an economy in greater need of electricity and fuel through taxpayers` money.

The bottom line for going after subsidies will not be as clear cut. The public is already suffering from a precipitous rise in the cost of living. The consequences, especially to lower-income households, could be devastating. The price they have to pay may have socio-political outcomes that could exasperate already prevailing uncertainties and insecurity.

Such considerations may not matter, nonetheless. The administration of Prime Minister Abiy is between a rock and a hard place. It just does not have the resources to continue subsidies. Between war, development aid on a freeze, impacted productivity, rising debt servicing and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic impact, the treasury is on life support.

It is not too late to thwart an economic calamity, though.

The first order of business should be to stop the war through dialogue to cease hostilities and a negotiated settlement. It is nearly impossible to pursue a civil war while planning for and running a sound economy. The uncertainties are too tremendous to pretend they do not exist. There could be a few and far apart examples of limiting the economic impacts of war. However, these are nowhere enough for a country to utilise its full potential and develop sustainably to forestall the burden caused by rapid population growth.

Stopping the war through a negotiated settlement can give the public and private sector the confidence to invest, expand, and stimulate the economy to return to a productive cycle. It will also unlock resources that must be diverted for war to be used for generative economic activities. Every Birr spent on arms is an opportunity cost against investments in schools and hospitals, two areas critical to building the human capital of a competitive economy.

To end the war will also help normalise relationships between Ethiopia and its development partners. The case for peace should never be made on financial considerations. For a conflict as the one in Ethiopia, it is a moral issue. But a perk, in this case, would also be improved relationships with the developed economies that have been instrumental to the country’s rapid economic development over the past two decades.

Too many lives, livelihoods and infrastructure have been devastated by this war. Civilian infrastructure has been destroyed, and millions have become alarmingly food insecure. The fastest way to rehabilitate citizens and carry out reconstruction is to work with development partners. Heavy lifting by the government alone could mean that no level of subsidies folded could pay for the destruction that has been incurred. Normalising relationships with development partners could open the tap for crucially needed recovery.

It may not be impossible to bring the economy back from the brink, nonetheless. But what the administration cannot do is turn time back. The war has taken its toll, and billions of Birr in public resources have gone into funding it. The treasury will continue to be strapped for cash for some time to come.

The impulse here could be to turn back to an old trick: turning up to eleven the money printers. The central bank can theoretically print as much money as the government needs but not without leading to a hyperinflationary event from which the Birr may never recover. The history of Hungary, Germany and even China during their wars are a testament to reckless money printing. In the case of Hungary, which had the highest inflationary rate in history, it saw prices double almost twice daily.

The lesser of two evils is thus to limit subsidies as much as possible. Phasing out subsidies could even be the healthier move for the economy that is under different circumstances. But it requires making political concessions while also taking a courageous move to address the structural imbalances within the economy and preserve the hard-earned savings of households.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 07,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1132]

Editorial | Nov 11,2023

Editorial | Dec 19,2018

Verbatim | Jun 22,2024

Fortune News | Sep 09,2024

Viewpoints | Aug 29,2020

Fortune News | Nov 03,2024

Commentaries | May 24,2025

Commentaries | Sep 08,2024

Radar | Dec 19,2020

Editorial | Jun 08,2024

My Opinion | 131819 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128203 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126147 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123767 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...