Viewpoints | Jun 18,2022

Sep 10 , 2021

By Matiwos Ensermu (PhD)

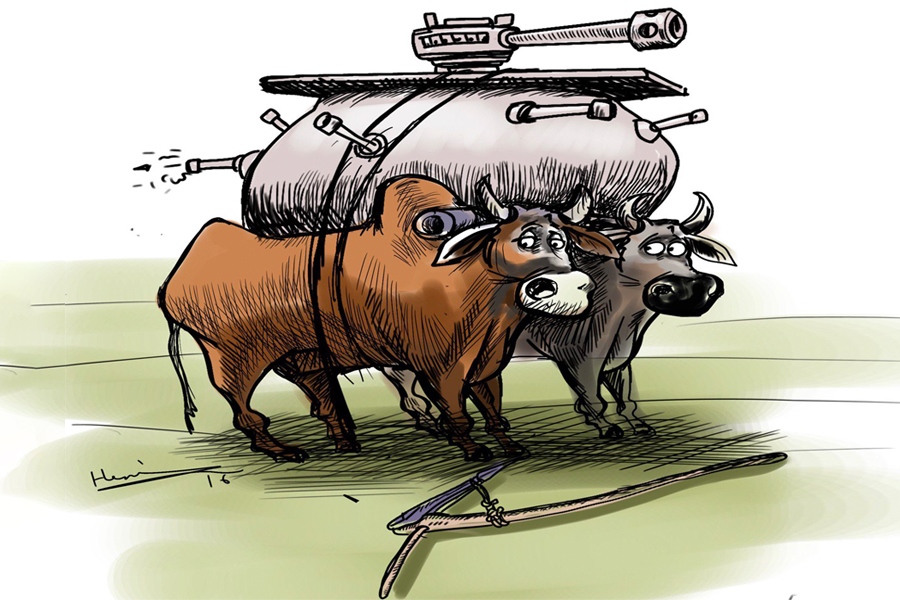

The government is clearly unnerved by Ethiopia's continual rise in food inflation, instituting subsidies and tax exemptions for imports. But none of these measures will go far until the obstacles along the value chain are addressed, writes Matiwos Ensermu (ensermujalata@gmail.com), associate professor of logistics and supply chain management at School of Commerce, Addis Ababa University.

Inflation is a general increase in the prices of goods and services in a country. There is no established formal inflation target, but policymakers generally believe an acceptable inflation rate is around two percent or a bit below. In Ethiopia’s case, up to 10pc could be tolerable. However, July's food inflation reached 32pc.

The federal government has responded by designating edible oil, sugar, wheat, and rice as tax-exempt consumer goods in response to the rising cost of living. This is hoped to encourage businesses willing to import the items while helping the government control the surge in food prices.

A variety of measures have been taken before against inflation. There has been an attempt at import substitution and agri-business incentives, including the Sheger Bread Factory, the largest bakery and flour plant, and a number of edible oil plants. However, such measures at federal, regional and city administration levels targeted at the end of the value chain will not bring meaningful change. There is no sign of decline in the price of food and non-food items regardless of government support, incentives and subsidies to wholesalers, retailers, manufacturers and importers. The ultimate retail price offered at the end of the long structure of the value chain to the consumers is still the same or rising month after month, year after year.

Based on empirical evidence over the past couple of years and decades, scarce supplies in a country with a growing population of over 110 million cannot be addressed through subsidy to the consumer side of the value chain. A closer look at food inflation in Ethiopia shows that the problem mainly emanates from a lack of policy shift in the agricultural sector.

Fragmented and characterised by low scale ownership, traditional farming systems, shortage of subsidy in financial and non-financial terms, lack of insurance for agricultural produces and a weak value chain governance are why food inflation is being exacerbated.

Addressing the weakest link of the problem should rather be the focus of policymakers when they provide resource support for actors in the economy. On the other hand, ignoring the main actors in agricultural production, the farmers, subsidising importers and consumers of city residents, and lifting tax for consumer goods without controlling the value chain, will fail to contain the inflationary pressure. The better policy measures to follow should be to shift the paradigm of where to intervene in resource support by addressing the weakest link in the economic system, agricultural underdevelopment.

Addressing the challenge can start by providing subsidies to the farmers. This is done by supporting farmers to get improved seeds, fertilisers, agricultural tools and machineries for mechanisation and gradual automation to enhance agricultural output and productivity on a large scale.

Another is providing price guarantees, a process involving the development of large warehouse facilities by the government at each woreda of each regional state to enable farmers to deposit their produce at market or above market price with targeted profit margins. This action has two benefits. The buyer is the government, at a profitable margin for a farmer that will ultimately build confidence and incentive for the farmer to produce more in the next season as they are protected from price fluctuation and manipulation by brokers in the value chain. In the occurrence of high food inflation, the government can also subsidise the market (consumers) by availing the already in stock agricultural products from the designated warehouses at subsidised (reduced) prices.

Yet one more important policy the government can follow is to regulate the agricultural value chain from source (farm gate price) to retail shops by establishing a maximum retail price policy. This is done by identifying the cost of producing consumer goods and setting reasonable profit margins for the farmer, wholesaler, importer, and retailer. The maximum retail price should be tagged to the product item by the retailer for transparency.

Finally, digitisation of the value chain from farmgate through GPS enabled wereda and regional warehouses, retailers, and wholesalers’ facilities. This is required for tracking and tracing agricultural commodities to avoid hoarding and increase visibility on the whereabouts of consumer goods until it is in the customer’s hand. Without addressing these glaring problems at value chains, no amount of subsidy to consumers and tax exemptions will improve matters.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 10,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1115]

Viewpoints | Jun 18,2022

Radar | Nov 20,2021

Radar | Jan 11,2020

Editorial | Jun 22,2024

Agenda | May 04,2025

Viewpoints | Aug 29,2020

Viewpoints | Sep 19,2020

Editorial | Jun 21,2025

Radar | May 04,2024

Radar | Mar 19,2022

My Opinion | 131970 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128359 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126296 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123912 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...