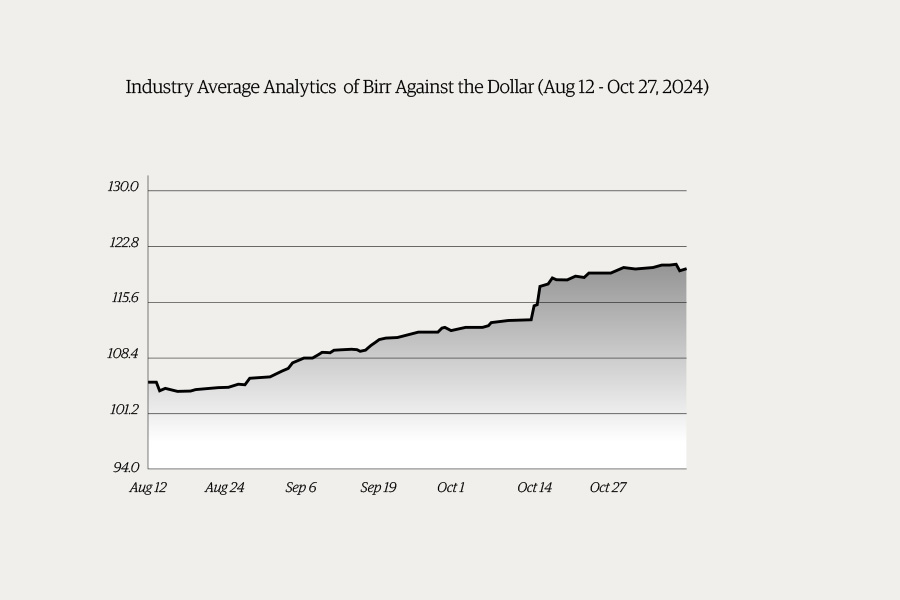

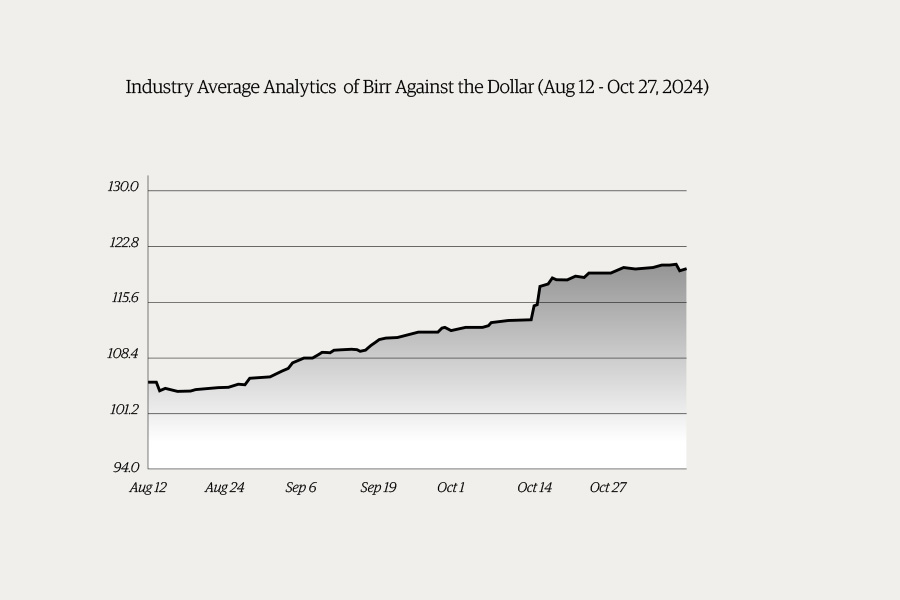

Money Market Watch | Nov 09,2024

Oct 26 , 2019

Many of the critics on the Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda are motivated by ideological stances and overlooked important omissions, argues this writer, whose identity Fortunewithheld upon request.

The recent debates on the government’s Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda are refreshing and encouraging. It is encouraging to know that the government has an overarching framework for its reform agenda. Whether we agree with the government or not, the overall economic policy direction is now clear.

It is also refreshing to see the debate that the Agenda has steered since its launch. Such debates, in particular by well-informed experts, are welcome and very important to inform the broader public and strengthen the policy initiative by providing productive input. I trust that the authorities are putting the initiative in the public eye with this spirit, and they are listening to critics with an open mind.

As much as I enjoyed reading some of the substantive debates in the media, including in this newspaper, I find the tone and focus of some critics pointless and unnecessary to the national policy discourse. Instead of assessing the contents, they focus on rejecting the idea that the reform is "homegrown" based on speculation.

Government representatives are on the record saying, the term is used to refer to the fact that the Reform Agenda is designed to address the country’s current economic challenges; was formulated by the government; and will reflect the views of the domestic public. If we want to make it truly homegrown, let us focus on providing productive and substantive feedback and challenge the government.

The debate on whether the agenda was prepared by the government or was copied from somewhere else is futile as the evidence offered to support such claims are based on speculation or resemblance. A recent critic argues that “there is no credible evidence to suggest that the Economic Reform Agenda was truly homegrown” because “there is no traceable background study”. It sounds like the writer is misinterpreting the absence of evidence (that he could not find a background study) as evidence of absence (that the government did not conduct a background study).

It is true that the government has so far released only a summary of its diagnoses and reform measures.

But does this automatically imply that the government did not conduct a background study? Had the government prepared the Reform Agenda without a background study, it would show up in the quality. The diagnoses would be wrong and the reform measures would not be targeted at the binding constraints facing the economy. If so, why don’t we direct our criticism to such substantive issues as the quality of the reforms instead of spreading a conspiracy theory about who might be behind it?

Other critics assert that it is not homegrown, because it is similar “to a typical IMF program[me] for reforming developing countries” or it is similar “in language and approach to that advocated by the World Bank and the IMF for many years”. By the logic of these critics, anything that resembles an IMF or World Bank policy prescription should have come from these institutions and cannot be considered homegrown.

In other words, a reform agenda that aims to safeguard macro-financial stability through prudent macroeconomic policies cannot be homegrown, because the IMF tends to advocate for similar policies. By the same token, any reform that focuses on promoting private sector development cannot be homegrown, because the World Bank advocates for liberal and private sector oriented policies. These are ideologically motivated criticisms and not reasoned arguments. Sound macroeconomic management and private sector development are almost universally accepted desirable economic policy goals and are not proprietary policies of the IMF and the World Bank.

Even if the government admits that the Reform Agenda was prepared with support from international organisations, would this mere fact discredit the value of the reforms? The important issue is whether the government is in the driver’s seat in setting policy priorities and goals, and not whether it has utilized technical support from foreigners. In fact, many developing countries, including China and India, actively utilize technical support from international organisations.

With this spirit, let me offer my two cents view on the contents of the Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda, focusing on whether it has identified the right set of challenges, reform priorities and goals.

Most of us would agree with the goals of the government’s reform agenda: job creation, inclusive growth, poverty reduction and paving a path to prosperity. The debate is on identification of key bottlenecks to achieving these goals and the policy priorities needed to address them.

On the diagnoses of the bottlenecks, I agree with the government’s assessment that growing macroeconomic imbalances, such as foreign exchange (forex) shortages, inflation, limited access to finance and a high debt burden are threats to the sustainability of the country’s economic progress.

The forex shortage has become so chronic that it is affecting every sector of the economy, including those that are not known to be forex intensive. We are not fully utilizing the industrial zones, upon which billions of Birr has been invested, in most part because the forex shortage has become binding and manufacturers could not easily access forex for imports of raw materials.

Many foreign investors, who have been attracted by Ethiopia’s success in building infrastructure and human capital, are sitting on the fence, waiting until the forex problem is resolved. Getting forex through the banking system has become so difficult that even legitimate importers are resorting to informal means. Consequently, the spread between the official and the parallel exchange rates has widened significantly to about 40pc recently.

Inflation has been running at about 15.5pc a year, on average, for the past 15 years. For one’s purchasing power to have remained the same over the past 15 years, her income should have grown at 15.5pc a year. Unfortunately, income growth for the majority of the population has been so sluggish that their purchasing power has been crushed. Such a high rate of inflation, which has continued to climb in recent months, is also a deterrent to private investment and future growth. Investors cannot plan and commit to long-term projects with confidence if prices are unstable.

Access to finance is also an important issue. Ethiopia is one of the least banked countries in the world with only about 35pc of the adult population having a bank account in 2017, compared to 81pc in Kenya and 59pc in Uganda. As the government’s presentation shows, access to finance stands as one of the main obstacles to doing business, in part due to low domestic savings but also because the government has been crowding out the private sector. We cannot expect the private sector to expand business and create jobs for the rapidly growing labour force if it has access to only a third of the economy’s limited financial resources.

Finally, close to 40pc of the country’s scarce foreign exchange earned through exports of goods and services (or about 55pc of exports of goods) goes to service our burgeoning external debt. In addition to limiting the government’s ability to borrow further from external lenders, high external debt distress, which is considered one of the early warnings of external crisis, discourages private investment as it creates uncertainty.

The government’s identification of structural and institutional bottlenecks is, however, not comprehensive enough. There is no question about the importance of already identified bottlenecks, such as access to reliable electricity, corruption and government inefficiency, poor internet service and inefficient logistics. The problem is with critical bottlenecks that are omitted from the document, including limitations of the land policy, poor contract enforcement, and (perceived) lack of an independent judiciary system.

The importance of contract enforcement and an independent judiciary is a no-brainer as investors need to have confidence in the independence of the judiciary and its ability to enforce contracts before committing their capital to long-term investment.

On land policy, the government’s reform agenda appears to acknowledge only the procedural difficulties with respect to lease rights. The fundamental problem is, however, the ruling party’s long-held ideological stance, which is also engraved in the Constitution, regarding land ownership. The success of the government’s Reform Agenda in certain areas could be limited if there is no change in land policy. Without allowing farmers to use their land as collateral for borrowing, I do not see much success in promoting access to finance to rural areas, which is one of the key objectives of the government. Research also shows that land tenure and ownership affect agricultural productivity.

Macroeconomic reforms are clearly outlined and well-targeted to the identified imbalances. However, the structural and sectoral reform priorities look incomplete and lack clarity and specificity.

For instance, the document is not specific enough on contemplated measures to improve governance of public institutions, implementing the telecom sector reform and logistics reform. Similarly, the plan to develop a legal framework to allow farmers to lease land use rights is not clear, since famers already have the legal right to lease their land. In general, there is a need to clarify how the new structural and sectoral reforms differ from existing policies and practices and how the reforms will transform the priority sectors.

In addition, key structural reforms such as judicial, the commercial law, and civil service reforms are missing. While the government appears to be making headway on judicial reforms and revising the commercial law, the failure of the Economic Reform Agenda to even acknowledge these important areas shows lack of synergy between the economic and legal reform agendas. The document is also tight-lipped on civil service reform, which is critical for modernising the institutional and policy frameworks – one of the key goals of the Agenda.

From the time frame of the Reform Agenda (which is three years) and its emphasis on macroeconomic reforms, it sounds that the priority for the government for the next three years is to correct macroeconomic imbalances. This is understandable considering the fact that macroeconomic imbalances cannot be ignored as they can quickly deteriorate. Furthermore, macroeconomic reforms can be considered low hanging fruit, as they can be implemented easily, most of them with a stroke of a pen.

Structural and institutional reforms, on the other hand, take time as they involve changes in institutional capacity and culture. Hence, I concur with the approach to focus on macroeconomic reforms as a near-term priority while gearing up effort toward addressing structural and institutional challenges over the long haul.

The authorities have stated that they are working on a longer term (10 years) development agenda. If so, I hope to see more granularity and comprehensiveness on structural reforms in the upcoming long-term reform and development agenda.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 26,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1017]

Money Market Watch | Nov 09,2024

Fortune News | Apr 19,2025

Verbatim | Dec 04,2021

Viewpoints | Oct 12,2019

Fortune News | Jun 15,2024

Radar | Apr 29,2023

Agenda | Mar 21,2020

Fortune News | Apr 03,2023

Viewpoints | Nov 30,2019

Editorial | Apr 26,2025

My Opinion | 131819 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128203 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126147 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123767 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...