Radar | Dec 19,2020

Mar 27 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

Few things speak louder of the poor state of a country than child labour. Technically, there are laws against this in Ethiopia. The labour law does not allow the employment of children under 14 for any purpose. If they are between that age and 18, there are limitations on the sorts of work they are allowed. The criminal code prohibits the trafficking of children for compulsory labour.

But often in Ethiopia, laws are taken as standards to live up to, not rules the violation of which are punishable by a court – hardly worth the paper they are written on sometimes. The same goes for child labour. It is rife and unimaginably ugly but a fact of life for anyone that bothers to take note.

The younger the child is, nonetheless, the harder it is to fail to notice. There was just one kid working on a minibus taxi as an assistant to the driver (redat) that was hard to fathom for me. He could barely shut the sliding doors and was barely visible above the car seats even when standing straight. He had dry plump cheeks and rough, cracked hands.

He was diligent and quick on his feet for his age. From his physical stature, he must have been around six. If he was older, he must be suffering from malnurished, making him one of the over 30 million people suffering from the same ailment in Ethiopia. He is also one of the 27pc of the youth population participating in the labour force. Many of these are robbed of their childhood and opportunities to learn. Worse still, they may not have guardians and could be one of 20,000 children trafficked into compulsory labour, according to Humanium, a children’s charity.

Given how harsh these conditions are, how vulnerable the children could be, and the long-term consequences on human capital, this is top of the agenda, right? Children growing up in debilitating poverty, selling their labour for sums well under the poverty threshold as an alternative to begging, is a priority for society, no?

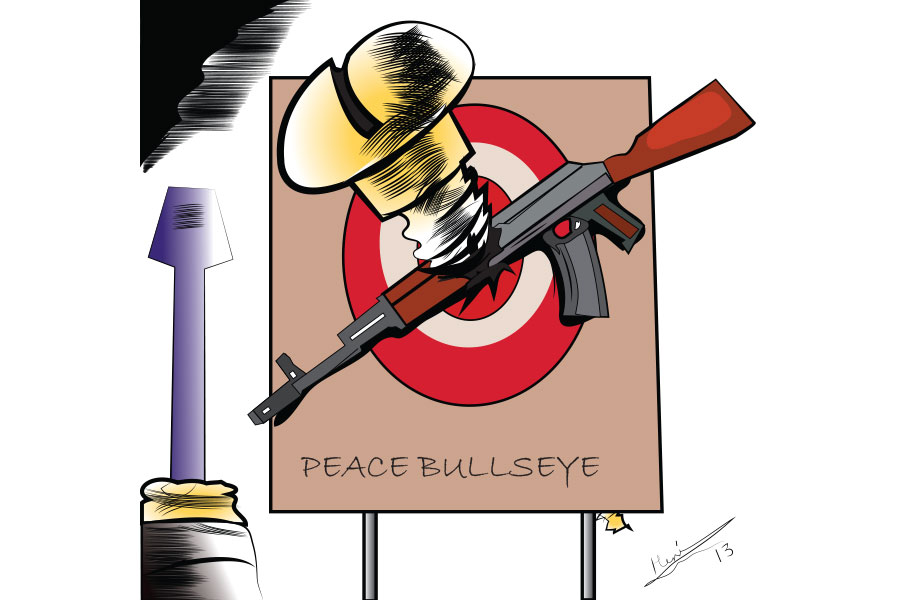

Not at all. There are neither rallies against child labour nor would anyone storm the streets over it. No one goes to war over starving children. What society puts on a pedestal –worthy causes to kill, maim and massacre for –are nationalism, historical memory and offenses and slights against one group by another. Child labour does not even get a measly hashtag, except perhaps on the World Day Against Child Labour, and even then because it does not hurt to virtue signal. Few in nonprofit organisations and government agencies working on children’s issues take a lasting interest.

Ethiopia is not alone in this. Most of the Global South – where all the bad things seem to happen – has high levels of child labour. More than a quarter of all children in poor countries are engaged in labour activities. UNICEF counts from five-year-olds who start providing 21 hours of unpaid housework services a week.

The culprit is poverty. If not enough wealth is created, millions of children will fall through the cracks to depend, or be forced to rely, on their labour to close income gaps for themselves and their guardians. Lack of wealth also means a government unable to provide a social safety net for its citizens, not even children.

There is no magic bullet. If there was one, laws should have worked. Enforcing them more strictly could help to an extent but not when poverty is entrenched and there is great demand for such cheap labour.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 27,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1091]

Radar | Dec 19,2020

Fortune News | Oct 30,2021

Fortune News | Jun 21,2025

My Opinion | Jun 07,2025

Commentaries | Apr 10,2021

Fortune News | Apr 29,2023

Life Matters | Aug 08,2020

Fortune News | Nov 07,2020

Radar | Feb 26,2022

Editorial | Jul 03,2021

Photo Gallery | 175973 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 166187 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 156607 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136865 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...