Commentaries | Apr 01,2023

Jul 1 , 2023

By Robel Mulat

In the tapestry of Ethiopia's attempt to reform its economic structure, an intricate blend of ambitious initiatives, domestic challenges, and global dynamics is unfolding. Its industrial parks (IPs), largely government-backed, have become the centrepiece of a drive to transform Ethiopia into an African manufacturing powerhouse. The strategy is to lure foreign investors with irresistible incentives, lower wages, and promises of a "Golden Reception" — a scheme providing preferential treatment, easy access, and logistical support to would-be investors.

However, beneath the allure of this glittering promise lies a less glamorous reality, fraught with struggle and turbulence. The largely female migrant workers who toil in these factories feel the brunt of these challenges.

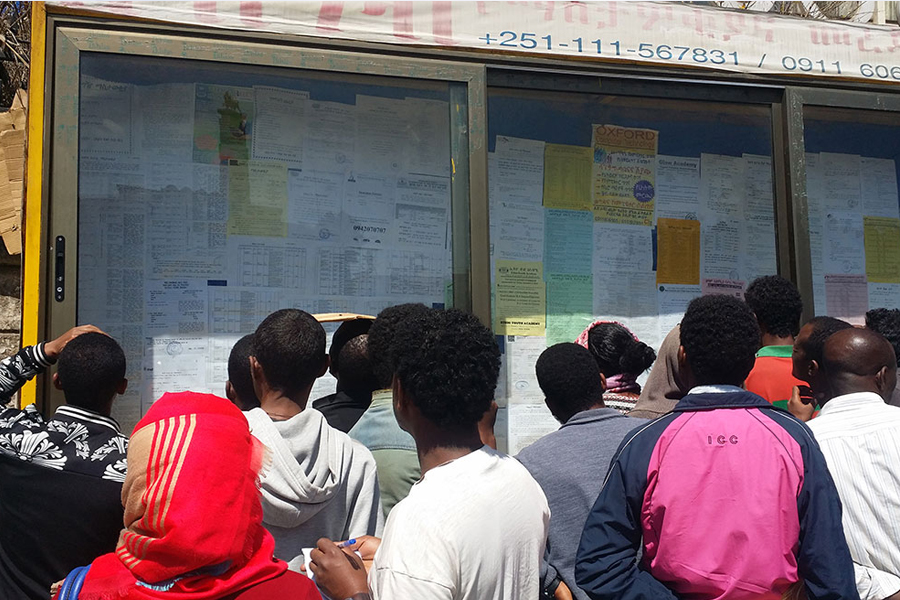

The dream sold to these workers is tempting: migration from rural lands into urban factories, with a promise of steady incomes and improved living conditions. Thousands have embarked on this journey, drawn by the prospect of joining the global supply chain and escaping agrarian lifestyles. Yet, the reality that greets them upon arrival is often far from the promise. Low wages, harsh working conditions, and inflation swiftly deflate their high hopes.

Ethiopia's urban migrant landscape is undergoing profound change due to extraordinary social, economic, and political upheavals. Global and regional shocks — such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Ethiopia's expulsion from the African Growth & Opportunity Act (AGOA), the Russia-Ukraine war, and enduring high inflation — are exerting significant pressure on the country's economy and its workers.

The government's Home-grown Economic Reform Agenda recognises the significant hurdles on the path to industrialisation. A primary issue is the underdevelopment of the manufacturing sector, which contributes less than 3.5pc to GDP and a paltry five percent of overall export revenues. In response, Ethiopia has been pumping significant investments into industrial park development. Hence, foreign companies are beckoned towards Ethiopia, attracted by the abundance of low wages.

The industrial park model's vision, with its focus on economic transformation, holds potential. The promise of increasing export earnings, absorbing a large labour force, and fostering industrial skills has undeniable merit. However, the country’s aspiration for industrialisation needs to balance the welfare and rights of the workers, who form the bedrock of this economic transformation. In the face of economic, social, and geopolitical shocks, the needs of these workers have become even more pressing.

Predominantly, young, rural women have found themselves at the heart of this new labour force. Deemed docile and obedient, they are the candidates for factory work. These women arrive at Hawassa Industrial Park, a major destination of the urban migration wave, armed with little more than disposable water bottles, inexpensive mobile phones, and the hopes instilled by recruiters' enticing promises.

Yet, the reality they encounter often starkly contrasts these dreams.

Historically, factories have found fertile ground for cheap labour in young, unmarried women, valued for their perceived flexibility, low cost, and propensity for obedience. Coupled with unfamiliarity with the industrial park culture and limited awareness of their rights, these women are nudged into accepting monotonous, strenuous work. Their voices are largely unheard as their plights remain invisible, for fear of job loss and in the absence of a minimum wage, strong unions, or social safety nets. This tacit acceptance perpetuates the status quo, providing the owners with a source of cheap and docile labour.

COVID-19, in particular, has had a profound impact on the industrial parks. As the virus spread across the globe, disrupting supply chains and triggering economic downturns, Ethiopia's manufacturing sector felt the squeeze. Production delays, a plunge in exports, and the shuttering of factories ensued. Women, youth, and low-skilled workers — groups already on the fringe — were pushed further to the edge.

Many migrant workers, faced with wage cuts and substantial food insecurity, were forced to return to their rural homes until their factories could reopen.

Another jolt came from the geopolitical arena. The war in the north and subsequent human rights concerns led the U.S. to suspend Ethiopia's AGOA privileges. This sudden move left businesses along the global value chain, which had depended on this concession to justify their investments in Ethiopia, in disarray. Job losses ensued, hitting poor women, primarily employed in the garment industry, disproportionately hard. The combination of job insecurity, inflation, and social instability has fostered a sense of alienation and despair among many migrant women.

Despite Ethiopia's efforts to attract foreign investors and develop its industrial capacity, the current model overlooks the needs of its workers, leading to inadequate living conditions and insufficient wages. The result is a vulnerable labour force susceptible to economic and social shocks, perpetuating a cycle of hardship.

Ethiopia's government needs to take a more holistic approach to its industrialisation drive.

Legislating a minimum wage standard could be a significant first step, ensuring a basic level of income for these workers. Investment in public housing projects could improve the living conditions of migrant women, whose problems are compounded by urban living expenses and the lack of affordable housing. Initiatives to promote awareness of workers' rights, as well as encouraging the formation of workers' unions, could empower them to negotiate fair deals for better working conditions.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 01,2023 [ VOL

24 , NO

1209]

Commentaries | Apr 01,2023

Viewpoints | Sep 04,2021

Commentaries | Mar 05,2022

Life Matters | Dec 17,2022

Sunday with Eden | Oct 10,2020

Editorial | Nov 11,2023

View From Arada | Aug 31,2019

Viewpoints | Sep 27,2025

Agenda | Jul 22,2023

Radar |

Photo Gallery | 177687 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 167901 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 158581 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136995 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 27 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...