Jul 6 , 2019

By Tibebu Bekele

One of the first feel good factors that accompanied the political reforms of the last couple of years was the release of political prisoners and journalists.

In an act that was supposed to usher in an era of forgiveness and reconciliation, thousands of prisoners in jails all over the country were released, resulting in an overwhelming joy for most people.

Not long after they left the jails, however, the public started hearing very sad prison stories. The former prisoners started talking about their horrible experiences there. Everybody knows jail is no holiday resort anywhere in the world, and it is common knowledge that Ethiopian jails are notoriously bad. However, what we were hearing this time was no ordinary prison tale. There were horrific allegations of torture, gross human rights abuse, sodomisation and even rape.

Well documented research has now established the fact that people exposed to of extremely stressful, life-threatening experiences suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The definition of PTSD according to the American Psychiatric Association is “a psychiatric disorder that can occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event such as a natural disaster, a serious accident, a terrorist act, war or combat, rape or other violent personal assault.”

I was discussing the events of the last few years with a lawyer friend when she dropped the question, “What has been done for these victims to help them deal with the trauma they faced?” I am afraid the answer is nothing. Not only did they not get any professional help to enable them to deal with their trauma, many were shoved right into positions and activities that are stressful for anyone, let alone people who have gone through that terrible experience.

And it should not come as a big shock if some of them snap under this heavy burden.

That got me into thinking about what people in this country have experienced in the last five decades of wars and revolutions. There were two major wars in the east with Somalia. There were two wars in Eritrea in the north: the independence war that went on for three decades and the relatively short war in 1998. There was the civil war that started in Tigray and spread to the whole country resulting in the toppling of the Dergue.

Then there were the internal power struggles of all different colored terrors - white terror, red terror and the latest anti-terror that were waged between different factions and the governments of the day. Add to that the recent phenomena of displacement of whole communities like Gedeo and many others like them in intercommunal tensions. It is not a pretty picture.

What does exposure to these kinds of traumatic experiences do to societies? It turns out that it is not just individuals that get traumatised. It affects whole societies too. Michael Wessells (PhD) says the following about his findings on the subject:

“The emotional, social, and spiritual wounds of war create a powerful impetus for continuing cycles of violence. Following the horrors of contemporary wars - ethnic cleansing, mass killings, rapes, destruction of homes and communities, child soldiering, mutilations, landmines, cultural and physical genocide - people often weave a sense of victimhood into their socially constructed identities.”

Listen to what passes for a conversation about Ethiopian politics, and it does not take a genius to see patterns that fit Wessells finding. Especially for political leaders and so-called activists, “weaving a sense of victimhood” into ethnic identities is sowing the seeds of revenge and exasperating mutual animosity between people.

This cannot continue without having devastating consequences.

Lessons have to be learned. In hindsight it is very clear that prisoners exposed to inhumane abuse and possible PTSD should have gotten the psychological support they needed to recover and heal. The fact that they may have won their freedom but their abusers have not faced justice does not help either since they do not have closure yet.

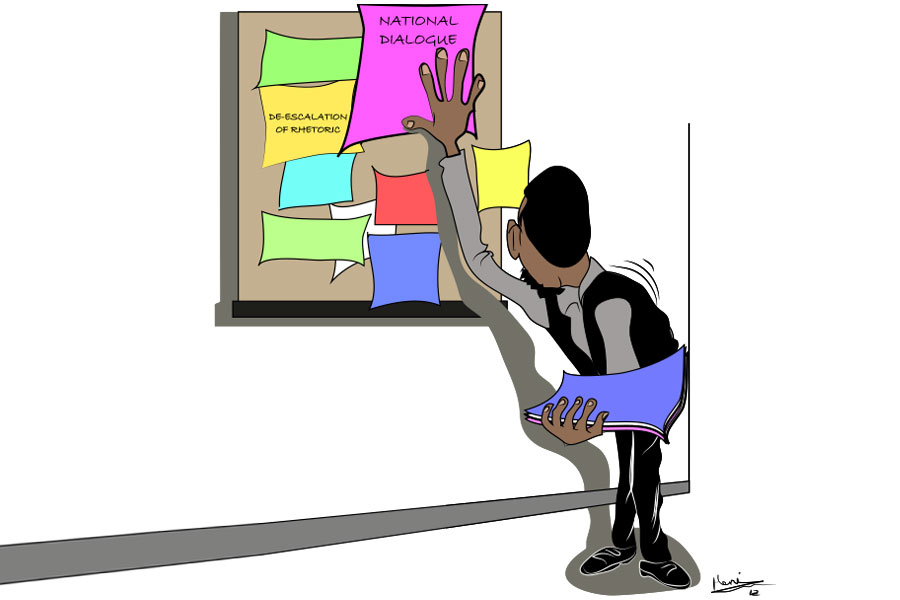

The larger society is not faring any better in this regard. The fact that we have not yet been able to have an open national dialogue on what happened and why is unhealthy. In the face of so much evident misconduct, there is very little remorse. How can you have peace in a society where those who are seen as perpetrators of crimes against humanity in some circles are seen as heroes by others?

The only way to peace is for us all to come to the proverbial couch. We need to start having open and honest conversations as a starting point for the healing process. As Wessells says, “Without coming to terms with the pain of the past, no bridge exists to a non-violent future, and emotional and social wounds continue to fuel cycles of violence. In this respect, healing is a means of conflict prevention in situations of protracted conflict.”

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 06,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1001]

Commentaries | Jun 25,2022

Commentaries | Jan 16,2021

Editorial | Dec 29,2018

Viewpoints | Apr 28,2024

Radar | Nov 09,2019

Obituary | Jan 25,2025

Radar | Mar 18,2023

Editorial | Oct 10,2020

Radar | Aug 03,2019

My Opinion | Jul 24,2021

My Opinion | 132151 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128561 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126482 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124091 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...