Radar | Aug 22,2020

Feb 8 , 2020

By

I was a senior year student when our Amahric teacher asked us to read Fiqer Eske Meqabir, Haddis Alemayehu’s 1968 novel that to this day remains highly revered in modern Ethiopian literature.

I was not impressed. I did not get it. The language was too complicated, although I was born and raised in an Amharic-speaking community. It was perhaps the third or fourth Amharic book I had ever read. It was like starting with The Very Hungry Caterpillar and jumping straight to Shakespeare. The odds were stacked against me. I could not have possibly understood the context and the prose to have appreciated its brilliance.

Why did this happen?

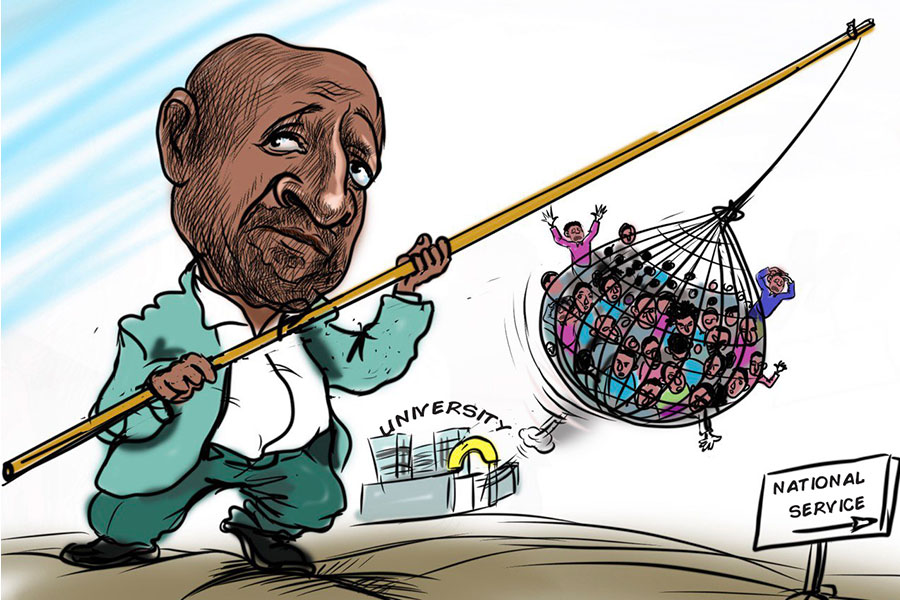

This little anecdote is actually highly symbolic of a lot of students’ experience in school. The primary and secondary education system lacks a certain wholesomeness, even in the private colleges that fleece parents of extraordinary sums of money every single year. We do not focus on them quite as much, because higher learning institutions often make schools look like factories of knowledge.

The typical school-aged person that goes to school in Addis Abeba takes Amharic and English courses 12 times over both primary and secondary schooling years. That was the case for me. But the only time I was asked to read a book was in my senior year.

Teachers greatly underestimate the year in which children get interested in any subject matter. Students are expected to slog through school, even if they do not see its application or relevance to real life.

How am I expected to be interested in numbers when there had been no effort made to show me its relation to the law of nature? What is the purpose of civics education when no attempt is made to correlate it to how society currently functions? How am I to have a greater grasp of language when I have never been encouraged to read books written in that very same language?

It is not clear. What was clear was that our teachers really wanted us to memorise a bunch of stuff they knew we would forget once the exams were over. Memorisation served the formal requirements that shaped the education system and gave it the facade of development.

For the teachers, there was no better way to give the impression that students have been given lessons. While education is much harder to measure, all a teacher has to do to prove that students have been given lessons is to show the home work and school-standardised tests they had been given.

The same goes for the management of schools. They do not get parents that ask why their children are not becoming more curious. They get the kind of parents who are interested to know how much their children have scored. The tests those scores are being based on are rarely a matter of discussion.

For the policymakers, memorisation fits nicely into nationwide standardised testing methodologies to grade the education system's development. It is expedient and less costly.

Memorisation is perhaps an even more desired policy in higher learning institutions where graduate volumes are highly political. But considering the small window in which it is possible to get children interested in subjects, it does more harm in primary and secondary learning institutions. As children grow older, it is harder to shape them.

Policymakers and parents should instead focus on how relevant the curriculum is and how relatable and fun teachers can make it for students. Showing how a certain subject applies in their daily lives can go a great length in helping students put things in perspective. Allowing them to participate in the process and using multiple resources (such as videos and fictional novels instead of textbooks) can help them define and build on their interests.

This is more work, but it is worth the hassle if the goal is to instill in children a more innovative spirit.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 08,2020 [ VOL

20 , NO

1032]

Radar | Aug 22,2020

Agenda | Oct 08,2022

Agenda | Jun 29,2025

Viewpoints | Nov 04,2023

Fortune News | Sep 10,2021

Editorial | Apr 22,2023

Commentaries | Nov 02,2024

Editorial | Apr 13, 2025

Editorial | Oct 21,2023

Fortune News | Mar 16,2024

My Opinion | 131507 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127863 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125841 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123471 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...