Radar | Oct 30,2021

Jun 18 , 2022.

Some of Ethiopia's economic policymakers may take solace from realising that inflation is a global phenomenon. It would be unwise to disregard their reading on what transpires around the world. In the United States, inflation reached a four-decade high; the United Kingdom, the European Union and China are battling the beast. Not even Japan, with an economy under the grip of deflation before last year, has been spared the scourge of soaring prices. At 3.81pc, the global average inflation rate is the highest in a decade, although lowered by one percentage point from last year.

Lockdowns caused by the pandemic, disruptions in logistics and transport, and over 11 trillion dollars in stimulus packages paid by advanced economies fuelled inflation. It is a bizarre occurrence where massive fiscal expansions created demand unmatched by supplies undermined by lockdowns and disruptions.

However, much of the world differs from Ethiopia's policymakers in the responses to tame the galloping inflation. They are going in the opposite directions.

Consumers in Ethiopia continue to be traumatized by surging prices. The year-on-year average headline inflation for May accelerated to 36.6pc, the highest for over a decade. Headline inflation in the consumer price index measures the prices of all goods and services, unlike core inflation which excludes volatile prices for food and services. The inflation rate for the latter is 10 percentage points higher.

Policymakers seem to have taken out-of-the-box thinking in responding to the inflationary pressure in the economy.

Take the central bank's recent move in deploying one of the policy arsenals under its belt. Its Governor, Yinager Dessie (PhD), sneaked a significant policy adjustment receiving hardly any attention it might have deserved.

The media and the elites were preoccupied with the usual issues of politics and conflict. And the public is consumed by anxieties over the rising cost of living. The budget bill grabbed the most curiosity, which Finance Minister Ahmed Shide tabled for Parliament's reading earlier this month. The attention was merited. A proposed sum of 786.6 billion Br in federal spending, over 15pc of GDP, could sound like a pretty penny.

Outside the spotlight, the central bank tweaked its reserve requirement for commercial banks. It halved the minimum reserve requirement to five percent of deposits and ordered them to meet a monthly average reserve ratio of at least seven percent. The adjustment erases the last policy update in September last year, which obliged the banks to double reserve ratios to 10pc.

Reserve requirements are meant to guarantee against the liabilities banks accrue on their balance sheets in the form of deposits. It is intended to help protect depositors against bank runs. Central banks have figured out another purpose for reserve ratios - as a monetary policy instrument. By raising or lowering reserve ratios, they can control liquidity levels banks hold, influencing credit growth.

In the parlance of the monetary gurus, "M2" is a measure of money supply that includes cash, checking deposits, and easily-convertible near money (deposits and securities). Either liquid or easily turned to cash, M2 serves as an indicator of inflation. Funds banks are obliged to hold in reserve accounts are not liquid; the more that goes into this account, the less liquid the industry. When the reserve ratio is lowered, liquidity grows by the number of funds immediately made available and through the money multiplier effect in the economy.

Deposits mobilised by banks reached 1.6 trillion Br by the end of the third quarter of the current fiscal year, 25pc higher than the same period in the previous year. A 10pc minimum at all times leaves 1.44 trillion Br available for borrowing. Halving the ratio frees the banking industry some 80 billion Br of funds to be available for lending.

The monetary policy instruments employed against rampaging inflation are lowering liquidity in the economy through reserve ratio management, interest rate adjustments or open market operations. The central bank is not making use of them. Since there is no developed capital market where the central bank can sell government securities, open market operations remain irrelevant. Deposit interest rates have remained unchanged despite climbing inflation. And the reserve ratio is lowered now, the opposite of what an inflationary economy needs.

What is the issue the central bank is trying to address? What is it that its governors want to signal?

The move should not be surprising. While inflation worries the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD), officials do not seem to believe that high liquidity in the economy is a significant driver. Neither Minister Ahmed nor the Prime Minister, in his address to parliament, connect lower public expenditure to inflation. The Administration has its sights locked on reducing deficit financing and the pressure of spending from debt service and defence to subsidies for essential items such as fertiliser. Inflation is considered a supply-shock phenomenon created by factors such as falling productivity and conflicts. Meanwhile, the growth in central bank advances to the government has been debated neither when Minister Ahmed tabled the budget bill nor when the Prime Minister addressed MPs.

If the policy wonks and members of the macroeconomic team advising Prime Minister Abiy are not persuaded that money printing is also a major cause of inflation, no wonder that the central bank, which has rarely acted independently from the executive, would move to lower reserve requirements at such a time.

It is not that supply-side issues are not at play here. An energy and food shortage has been created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions. Domestic supply shocks include widespread conflicts impacting agricultural productivity and the worst drought in decades in the south and east.

The moves by the central bank have also contributed, nonetheless. Money does not grow on trees; but if it did, it would become automatically useless. The same logic applies when the amount of money in the economy grows suddenly by nearly a third in just a year, far higher than the single-digit GDP growth. Contributing to this money growth is not just central bank printing money but also credit growth by banks. The latter is tied to reserve ratios; whatever the amount banks are not obliged to hold, they are likely to lend out.

Although credit in the economy has been expanding, the private sector has not benefited as expected. Governor Yinager should persuade his counterparts at the Finance Ministry not to crowd out the private sector for loanable funds. The federal government's appetite has been unquenchable and unlikely to be in the coming fiscal year. It expects to fund about a third of its spending through domestic debt. If last year were any indication, this would likely come from local banks buying treasury bills. If deficit financing was limited, especially by avoiding a supplementary budget, the private sector would be the beneficiary of credit growth – a better prospect as it could use it more productively.

The move to lower the ratio should be regrettable. It is untimely. It is like prescribing a poison pill to a patient diagnosed with other ailments. If it were not for the uncertainty it would add to the banking industry, not to mention the economy, it is time to raise the ratio higher. The central bank has shot itself in the foot again, with its latest move exacerbating inflation, not taming it. The least it could do was salvage the best out of a bad situation.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 18,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1155]

Radar | Oct 30,2021

Fortune News | Dec 25,2021

Radar | Jun 20,2020

Radar | Jul 07,2024

Radar | Aug 18,2024

Fortune News | Dec 09,2023

Radar | Sep 10,2022

Fortune News | Nov 12,2022

Radar | Oct 23,2023

Radar | Nov 26,2022

Photo Gallery | 180281 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170478 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161507 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137269 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 2 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has scrapped the credit-growth ceiling that had s...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

The burgeoning data mining industry is struggling with mounting concerns following th...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

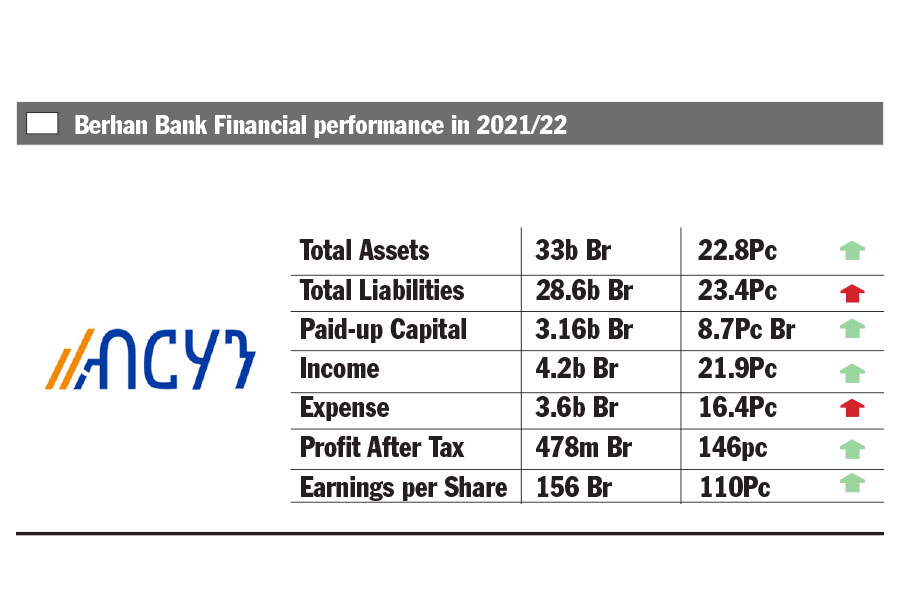

Berhan Bank has chosen a different route in its pursuit of a new headquarters, opting for a transitional building instea...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Nib International Bank S.C. has found itself at the epicentre of a severe governance...