Jul 20 , 2024

By Matias Assefa

Despite promising reforms, the NBE’s new policy framework faces entrenched issues: underdeveloped financial markets, a heavy reliance on primary commodities, and a historical government influence. True change demands statutory autonomy and deeper market reforms. Until then, Ethiopia’s monetary policy remains a quagmire, argued Matias Assefa (matias.assefa@gmail.com), who studied economics at Addis Ababa University and is now an economic and business analyst based in Addis Ababa.

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) announced a "new" monetary policy framework with much publicity. The central bank described it as "a historic step that will better align its policy tools with modern central bank practices and address some long-standing weaknesses in the macroeconomic and banking environments."

This raises the critical question: Is this move mere grandstanding, or is it economically substantive?

There are limitations to what monetary policy can achieve. Multiple supply-side and demand-side factors affect output and inflation; not all are domestic. Greater coordination with other policies, particularly fiscal policy, is always essential. The new monetary policy framework is welcome and long overdue, but for now, it seems more like an admission by the government that the old one failed rather than a silver bullet capable of shaping important economic outcomes.

The 2009 framework's strategy was based on monetary targeting, with reserve or base money as the operating and broad money (M2) as the intermediate targets. The NBE applied direct, indirect, or statutory monetary controls as it saw fit. However, the effectiveness of reserve money targeting was questionable due to the absence of a stable relationship between reserve money and macroeconomic goal variables such as domestic income and inflation. This inconsistency invalidated base money as a guide to monetary policy, rendering the monetary targeting regime a toothless tiger.

Despite this, the NBE refrained from abandoning it.

The old framework also faced issues of central bank autonomy. The proclamation that reestablished the central bank in 2008 and the Constitution (in force since 1994) made the NBE accountable to the Prime Minister, with the federal government having statutory authority over monetary policy and foreign exchange regulation. The law required the central bank to make advances to the government with limited constraints.

Thus, Ethiopia's "monetary authority" was essentially the government, exposing the NBE's policy to fiscal and political pressures, and blurring the lines between the central bank and the Treasury (Ministry of Finance). The NBE lacked a strong track record of transparent and timely policymaking, with hardly any public pronouncements about monetary policy committee meetings or proposals. The central bank struggled to recruit and retain highly qualified staff due to less attractive rewards package and working conditions, which are vital for its proper functions.

Beyond the deficient monetary policy framework, other headwinds impeded effective monetary policy transmission through the economy.

Ethiopia’s underdeveloped financial system, including nascent securities markets, a highly concentrated banking industry favouring the state, and a "managed-float" exchange rate policy with currency and capital restrictions, inhibited the smooth functioning of some transmission channels like interest and exchange rates, while rendering others like market expectations irrelevant. The economic structure's inclination towards primary goods production also posed a problem, as purchases of these goods are less credit-dependent and interest rate-sensitive.

The coexistence of formal and informal financial sectors, with the latter being relatively larger, complicated the situation. According to the 2021 Global Findex report, only 23pc and five percent of adults who reported saving and borrowing money in Ethiopia, respectively, used the formal financial system. This is problematic because the informal financial sector is not directly amenable to monetary policy measures.

The NBE has failed - rather frequently - to achieve its mandated mission of stability in inflation and the foreign exchange market. Between 2006 and 2020, consumer price inflation often deviated from the NBE’s single-digit goal, averaging an annual rate of 15pc, while also being unstable. Similarly, foreign exchange reserves covered, on average, less than two months of imports, far below the NBE’s goal of a three-month buffer. The exchange rate depreciated at variable rates, strict foreign exchange rationing was common, and the parallel market recently traded at a record premium of over 100pc.

Against this backdrop, a new monetary policy framework emerged. While introducing some novel elements, it retains certain old traits that have long plagued monetary policy.

The NBE appears to be moving towards an inflation-targeting regime, with low and stable inflation as its primary goal. It intends to use a benchmark policy interest rate – the national bank rate (NBR) – as a way of signalling its policy preference. Unlike the previously haphazard mix of diversified policy instruments, open market operations (biweekly auctions) are envisaged as the primary policy instrument.

A bill tabled to lawmakers in June 2024 defines a constraint on direct monetary financing of the government – no more than 15pc of the average annual government revenues of the previous three years and only in the form of temporary overdrafts, though loopholes remain for government exploitation.

However, the central bank will continue to report directly to the Prime Minister, and the unfavourable financial and economic conditions will not disappear in the foreseeable future. Given this, the odds of the new monetary policy framework faring better than its predecessor are, at best, precarious.

Several measures could help monetary policy out of its current predicament.

The NBE can be restructured as a technocratic institution to function effectively, gain public trust, better handle political pressures, and adequately analyse and forecast complex and dynamic economic and financial situations. This would enhance its ability to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation objectives. It should be granted statutory autonomy, making it directly accountable to the public through Parliament and shifting the balance of voting rights in the Board of Directors from government representatives to technocrats. This requires the chairman to come from the latter with the requisite expertise and integrity. The central bank's operational autonomy, transparency, and communication with the public should increase too.

Modern monetary policy frameworks also typically have independent and transparent central banks.

The proclamation and the Constitution should be amended to reflect these changes and increase the policymaking and executive power of the NBE. Taking precedence over the establishment proclamation, the Constitution needs amendment to avoid conflicts of interest between the central bank and the Treasury. The financial system’s structure and depth should be improved to ensure better monetary policy transmission, involving a competitive banking industry, developing financial markets with the necessary regulatory environment, enhancing the role of the private sector, and expanding the formal financial sector.

Lastly, the economy needs to transition away from primary commodities production, which is daunting.

This does not mean that these ideas are lost on policymakers. The current government has already embarked on addressing some of these issues in line with its "Homegrown Economic Reform Plan" and the NBE’s medium-term Strategy Plan. For instance, the country’s first mobile money service has been launched to reform the financial system and ensure financial inclusion. Parliament passed a bill to establish a capital market, the Council of Ministers approved a draft policy to open the banking sector to foreign competition, and the NBE has committed to facilitating well-functioning interbank money and foreign exchange markets.

The private sector can now receive the lion’s share of bank credit, while various measures are being taken to diversify the country’s economy and promote structural transformation.

However, until these efforts culminate and the other suggested measures are implemented with the requisite political will and commitment, monetary policy in Ethiopia will likely remain a quagmire. The NBE will struggle to play a meaningful positive role in the absence of macroeconomic stability or to claim legitimate credit when it exists.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 20,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1264]

Radar | Feb 26,2022

Radar | Apr 17,2021

Sunday with Eden | Jan 07,2023

Commentaries | May 08,2021

Radar | May 06,2025

Photo Gallery | 179003 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169199 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 160074 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137135 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

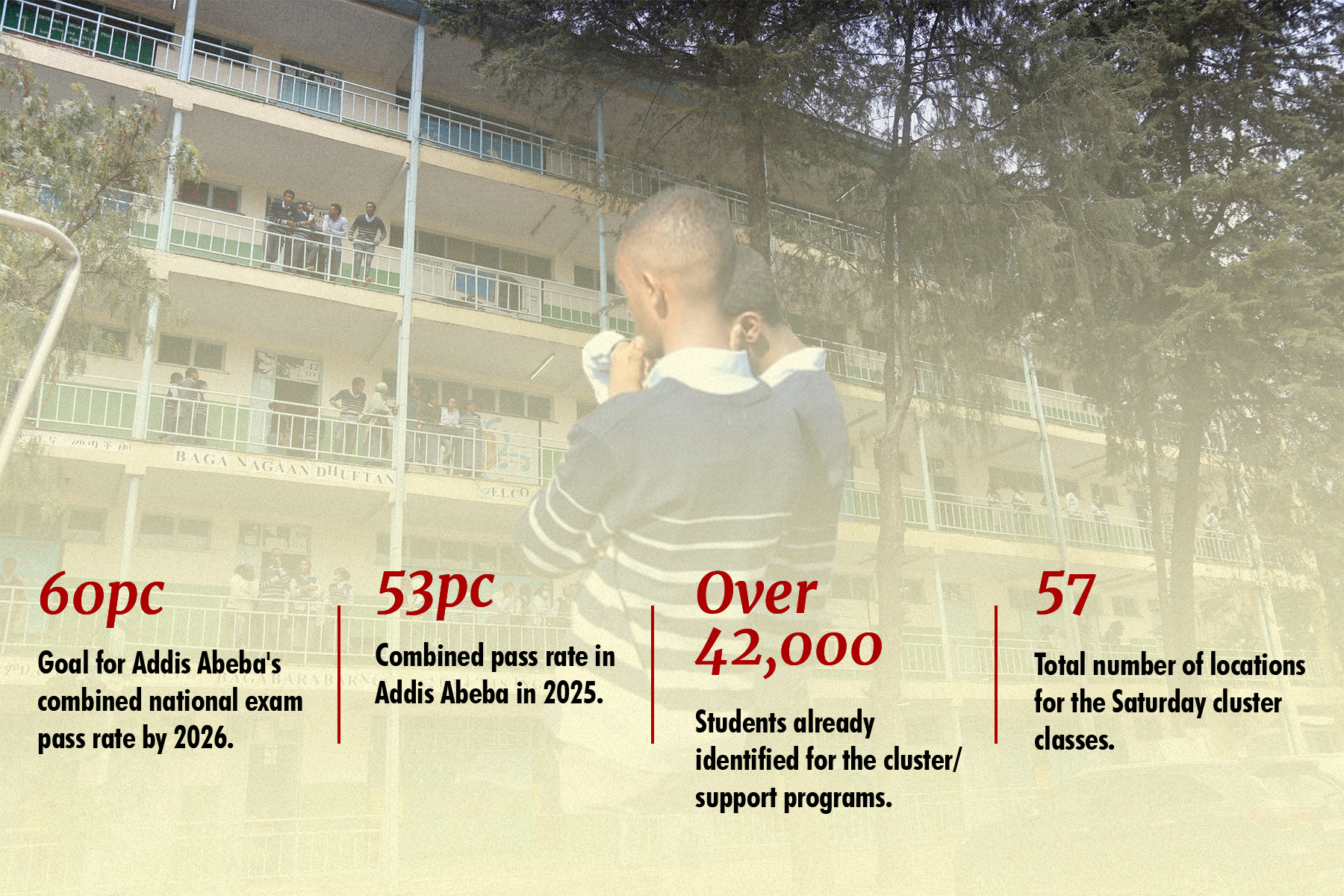

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...