Viewpoints | Jul 29,2023

Apr 3 , 2021.

As an Auditor General, he was not the most conspicous of officials in the mainstream. But the end of the tenure of one of the most vocal public servants over the past decade – Gemechu Dubiso – should have aroused more attention. If there was one person in government who could plausibly claim that they untiringly called attention to the mishandling of public resources, which would later lead to unsustainable debt, it was him.

Gemechu’s job of identifying poor management of resources over the past 12 years was, however, more than helped by the grossness of how government agencies and state enterprises were going about their business. It would be the nightmare of any public sector auditor to learn that massively capitalised state enterprises such as the then Metals & Engineering Corporation (MetEC) and the Ethiopian Petroleum Supply Enterprise went six years without being audited. The biggest offender was the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. It lagged behind its audit reports by seven years.

In 2019, Gemechu's office announced that 16 public projects were commenced without a feasibility study and scrapped after a quarter of a billion Birr was spent on them.

No surprises then when in the end the Sugar Corporation had run into debt worth about 70 billion Br that it could not pay, or that MetEC eventually became synonymous with impunity mere years after its establishment. With courage and conviction, Gemechu spoke out against it every year to a parliament that sat back as state-owned enterprises' debt mounted to 780 billion Br. Over 90c of this was accumulated over the past decade. Much of this is owed to Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), which has risen to become a de facto policy bank and external lender.

The response to state enterprises' debt problem is the Liability Asset Management Corporation, which was established earlier this year. It has nearly been under the radar, but it is no small thing. Armed with a capital of 570 billion Br, it is technically a state-owned enterprise. The twist is that its primary function would not be to play an economically productive role, such as producing goods and services. It is not even primarily a profit-making enterprise.

It is meant to come to the rescue of state enterprises that have run into dire financial straits by soaking up their debts. It plans to absolve them from a fifth to the entirety of what they owe. In the latter category would be the Sugar Corporation and the Ethiopian Railway Corporation. The likes of Ethiopian Electric Power will see a fifth of their debts taken off their books.

On the surface, it seems like a neat trick. The Liability Corporation would fund itself mainly from privatisation proceeds and the sale of telecom licenses to settle a significant amount of debt. Voila! The enterprises would be bailed out and go back to being a productive force in the economy.

In the short term, this can indeed work out. Like a firm that auctions off its valuables to pay for its outstanding debts in times of financial constraints, current liabilities on some of the state enterprises could be made to disappear. But in establishing this Corporation, the government has created an entity that is too big to fail.

How big of a gamble this is cannot be understated. There are no clear plans on how the Liability Corporation would continue to stand on its own two feet in the future. The Finance Ministry would like to see it become a “commercial entity with professional management” that can engage in the economy's profit-making sectors. It is suggested that the entity would make further investments, including from “underutilised public assets,” to generate revenue.

All the roads to hell were paved with good intentions.

The problem with engaging in investments is that they could fail, as state enterprises that precede the Liability Corporation, such as MetEC, have shown. But the former would be much more consequential in doing this. The bankruptcy of any one state enterprise will have massive consequences on the economy; the failure of a Corporation established to soak up billions of dollars in debt, however, may very well take the economy down with it.

More alarming is that the Liability Corporation, in its conception, is not meant to address the initial reason debt by state enterprises became inflated in the first place. To their credit, policymakers at the Finance Ministry admitted that they would not be entirely out of the woods unless a significant overhaul of public institutions occurs. The move toward a more private sector-led economic system is an essential component here. On average, the private sector is much more responsible with resources if competent regulators oversee it. There is also an element of merit to adding levels of checks to planned public projects, as was a mandate given under an office to the Planning & Development Commission after a bill was proposed in 2019.

But none of these justify giving a new lease of life to enterprises that have shown such gross maladministration born out of political corruption. It boggles the mind that any public project could have a cost-overrun between 60pc to as high as 400pc, according to a report from McKinsey & Company. It is taxpayers that are footing the bill to bail out state enterprises’ exorbitance. If consideration is not taken to overhaul political and economic institutions, the Liability Corporation will need bailing out in a few short years.

That projects under these enterprises, which operated above a checks and balances system, would run themselves deep into debt was foretold, no less by the Auditor General to members of parliament. But a web of patronage, corruption and cronyism allowed them to continue under an atmosphere of impunity.

The administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) vows that this will not continue. It would do well to remember that previous governments have made the same promises against political corruption. Unfortunately, they became hegemonic, which required creating a protected political class and web of cadres. This group's loyalty could only be bought, at least to an extent, by giving them free rein over the exploitation of economic resources.

It is a competitive political system that builds strong institutions where economic and political power is checked. Without addressing this central problem, moving around debts and selling assets will only be a temporary break from a much more intricate ailment.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 03,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1092]

Viewpoints | Jul 29,2023

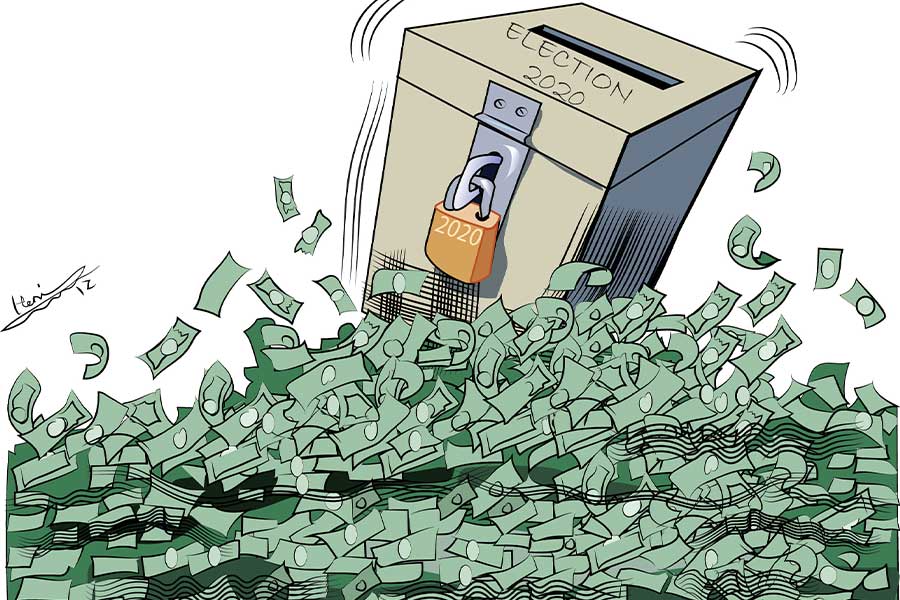

Editorial | Feb 01,2020

Commentaries | Oct 02,2021

View From Arada | May 11,2019

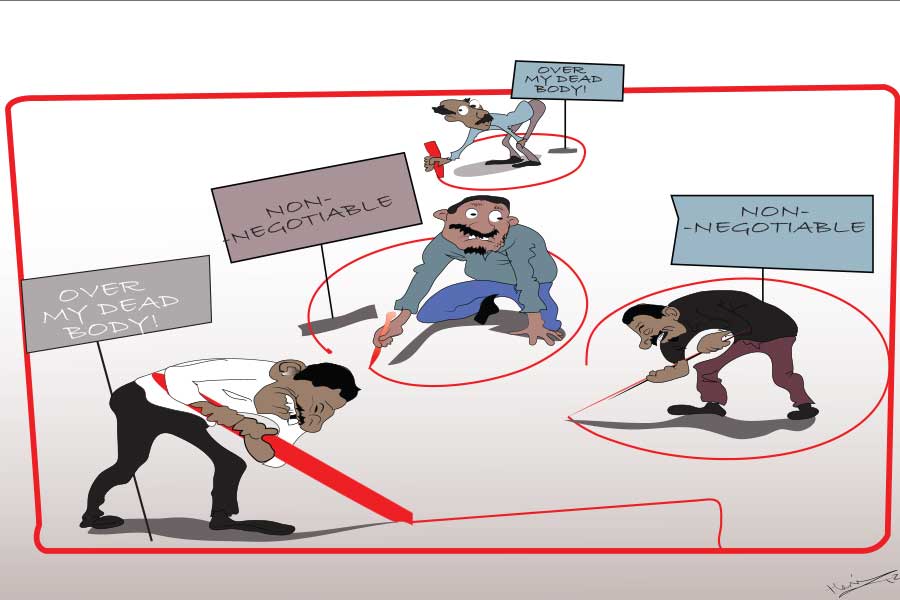

Editorial | Jan 04,2020

Viewpoints | Jul 18,2021

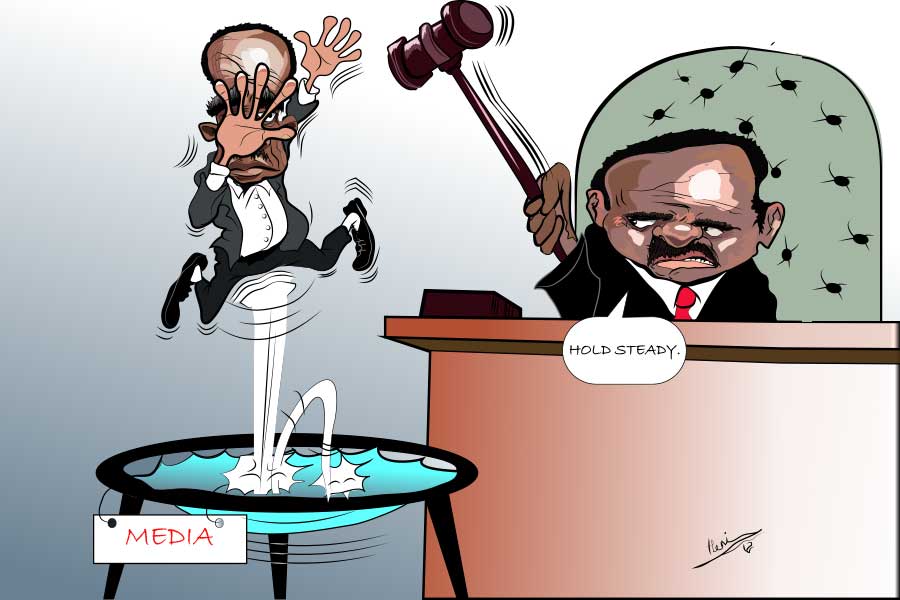

Editorial | Jul 18,2020

Commentaries | Aug 16,2025

View From Arada | Jul 26,2025

Editorial | Feb 27,2021

Photo Gallery | 179902 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170097 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161081 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137228 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 2 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has scrapped the credit-growth ceiling that had s...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

The burgeoning data mining industry is struggling with mounting concerns following th...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Berhan Bank has chosen a different route in its pursuit of a new headquarters, opting for a transitional building instea...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Nib International Bank S.C. has found itself at the epicentre of a severe governance...