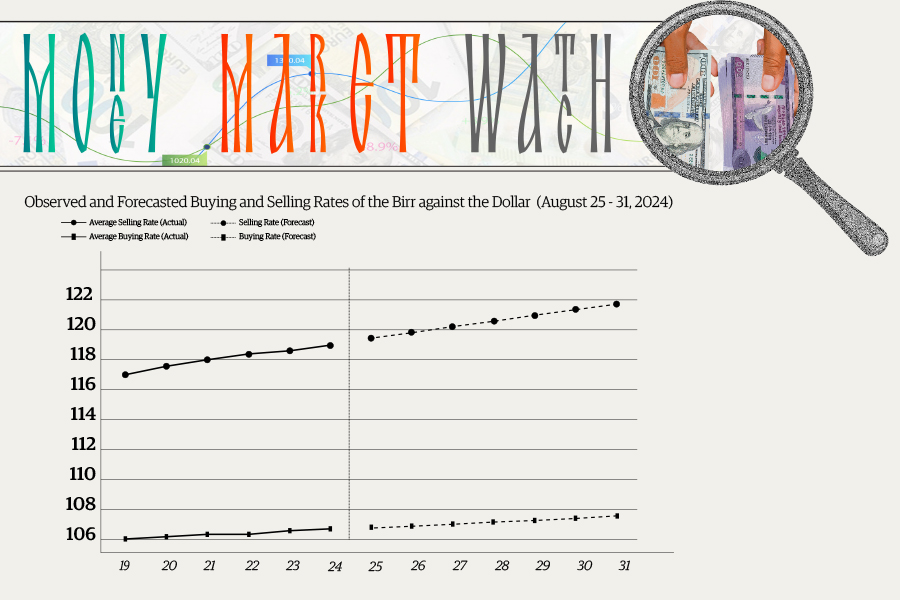

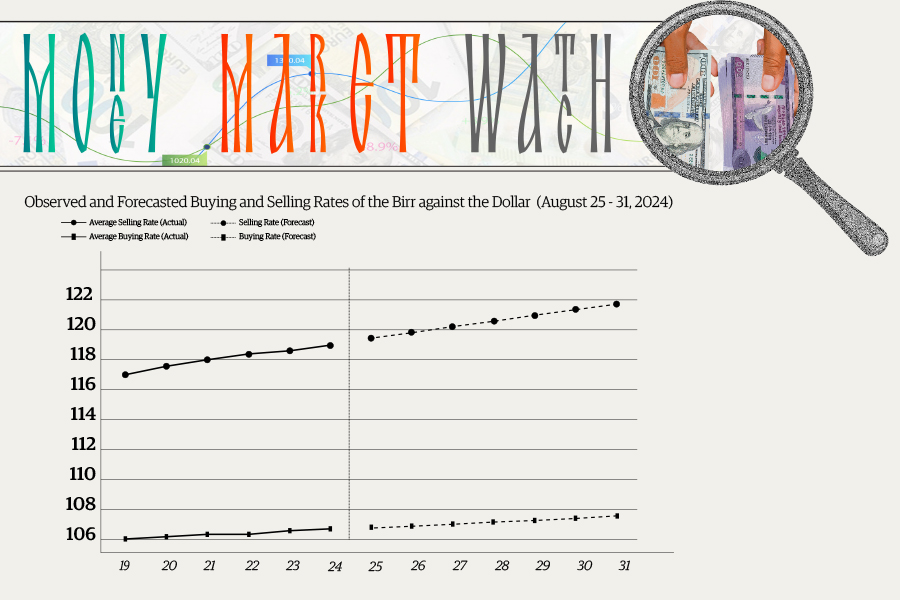

Money Market Watch | Aug 25,2024

Feb 9 , 2019.

Issayas Dagnew, a senior executive at Ethio telecom, is a brother to Kinfe Dagnew, a high brass military general who was also the founding CEO of the state-owned Metals & Engineering Corporation (MetEC). Running these government corporations for much of the last decade, the brothers now find themselves behind bars, locked up since November 2018 under investigation for grand corruption and embezzlement.

Kinfe has since been charged. His younger brother was granted the right to bail by the Federal High Court, which was overruled by justices at the Supreme Court. The basis for the decision by the Supreme Court was in response to an appeal by public prosecutors, pleading for an additional 10 days to press charges against Issayas. Well over two weeks have since passed, but neither have federal prosecutors charged him, nor has he been released against a bond as the lower court ruled.

Issayas’s case is regrettably not isolated. There have been a couple of other individuals detained on suspicion who remain behind bars even after judges granted them a right to bail. They serve as an unsettling trend dashing the faith in many.

The hope that the current political transition kindled among citizens was that the particulars of democratic governance have to be relearned. The fairness of the justice system, the assertiveness of judges to remain true to their conscious in upholding the law, and the professionalism by public prosecutors would not be restored as soon as possible. Indeed, bad habits die hard.

True. The horizontal, as well as vertical, hegemony of the EPRDF within the state has sapped the professional and constitutional autonomy of institutions, a matter that can only be addressed piece by piece, much like how Rome was built. It is a matter that is especially crucial and should strictly be stuck to, as the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) tries to chart a way through an unpredictable and delicate political transition.

Part and parcel of this transition are the federal probes to account for those who allegedly committed human rights abuses and misappropriated public funds. The federal investigation underway on MetEC to uncover alleged crimes that mainly involve unlawful procurements is the high profile case public prosecutors are currently trying.

Given that the probe is taking place within an atmosphere of confusion and mistrust, and at a time of transition, there have been early calls for the fairness of the court proceedings. The right of the suspects to be considered innocent until such time that their alleged guilt is established in a court of law stands tall in this call.

However, this has mainly focused on the behaviour of those in the judiciary, a body with a constitutional guarantee to its independence that only devolved as the executive grew too powerful to be checked and held to account for the actions it takes. There are commendable measures taken to assert the independence of the courts. Not so with the ongoing reforms to address the professionalism of law enforcement agencies under the executive.

As investigations intensified, police have recurrently appealed to the courts for additional custody rights over suspects; for the most part, they have been obliged. But there have as well been instances where judges denied police custody rights and granted bail to the suspects as is the case with Issayas and a few others demonstrated.

The history of bail rights in Ethiopia lend themselves to disrepute and have served as precursors to the abuse of the entire justice system by the powerful political establishment. Contrary to legal tradition, there has been of late a new culture of holding suspects in detention by employing procedural tools with little relevance to the substantive matters they are supposed to be used for.

This regrettably damaging culture perhaps began with Seyee Abraha, a former strongman of the TPLF ousted from power in the early 2000s. Arrested in the guise of corruption charges, judge Birtukan Mideksa, currently the head of the Electoral Board, granted him bail rights at that time. Seyee, in one of the most repeatedly witnessed perversions of the justice system under the EPRDF regime, did not spend a day outside of jail before police arrested him again from the streets of Piassa.

Within the subsequent days, a bill denying suspects of corruption a right to bail was legislated by the federal parliament. Seyee would have to spend the following half decade in prison before the Federal Supreme Court sentenced him to a similar period of imprisonment. Sadly, far too many others suffered due to this political instrument since.

Seyee’s case was a signifier that power play dynamics often motivate federal investigations on corruption allegations. They do not merely come from judicial processes thus the procedures until charges are pressed also require a similar level of scrutiny to be considered fair.

The Office of the Attorney General is an institution that is under the whims of the executive. Parliament only approves a nomination for the Minister of the Office by the Prime Minister. But the Minister answers to the Prime Minister, a structural relationship not peculiar to Ethiopia.

Even in countries with mature democracies, there has been an implicit association between the Attorney General and the head of the state or government that leads to independence being compromised. The case of the United States is especially illuminating in that, despite recent outrage, President Donald Trump asserted that former Attorney General Jeff Sessions should have been loyal to him. Previous practices since the 20th Century show that, indeed, the office, under the Department of Justice, has mostly been influenced by the White House.

It is a matter of course that both the police and the Attorney General’s Office practice non-partisanship and professionalism. It is not entirely unclear, however, how this can be achieved if they owe their accountability to the executive branch in the state.

The problem is intensified when the history of the relationship between the executive and other bodies of the state are taken into consideration. It would be naïve to expect professional autonomy from institutions that have seldom been encouraged to show it for a long time, if ever.

Worse, it does not lend confidence in the handling of the current corruption probe that similar tactics, such as unbalanced documentaries, to ones aired under previous administrations were utilised.

Thus, while police and the Office of the Attorney General may have been entirely within their rights, the matter should be approached while being informed by history.

There must be steps taken to ensure the integrity of the Attorney General’s Office as well as the Federal Police by moving them away from the partisan political agenda of those in the executive. If voices are emerging with a call to make the Office of the Attorney General accountable to parliament, it is only informed by the recurrent abusive history of the past. It should be understandable, because it is hinged on the hope that such a move could serve to disempower the executive.

But neither is it unprecedented - Canada and Britain have a similar system - nor would it be without merit given that the executive has been historically over-empowered.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 09,2019 [ VOL

19 , NO

980]

Money Market Watch | Aug 25,2024

Films Review | Oct 09,2021

Agenda | Feb 29,2020

Commentaries | Dec 02,2023

Fortune News | Jun 14,2020

Fortune News | Apr 21,2025

View From Arada | May 21,2022

Letter To Editor | Mar 02,2019

Sunday with Eden | May 31,2025

My Opinion | 131974 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128363 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126301 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123917 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...