Featured | Jan 08,2019

May 4 , 2019

By Gedion Timothewos

Free speech should be protected. But tolerating hate speech would not be a prudent course of action to take when the life and liberty of fellow human beings is on the line, argues Gedion Timothewos (PhD), state minister at the Federal Attorney General’s Office.

Although I disagree with the editorial of this publication, headlined “Protect Free Speech, Tolerate Hate Speech” [Vol. 20, No. 989, 2019], it should be underscored that our difference of opinion falls within the realm of what John Rawls has referred to as a “reasonable disagreement”.

This is to mean that it is a disagreement that would exist and persist “even among people who might be adequately informed, reflective, sincere, and bear one another no ill will”.

My arguments in this letter are intended to present my perspective on the issue of “hate speech” while recognizing that the perspective reflected in the editorial section of this publication happens to be from an informed, reflective and sincere compatriot arguing for what one genuinely thinks is in the best interest of the country.

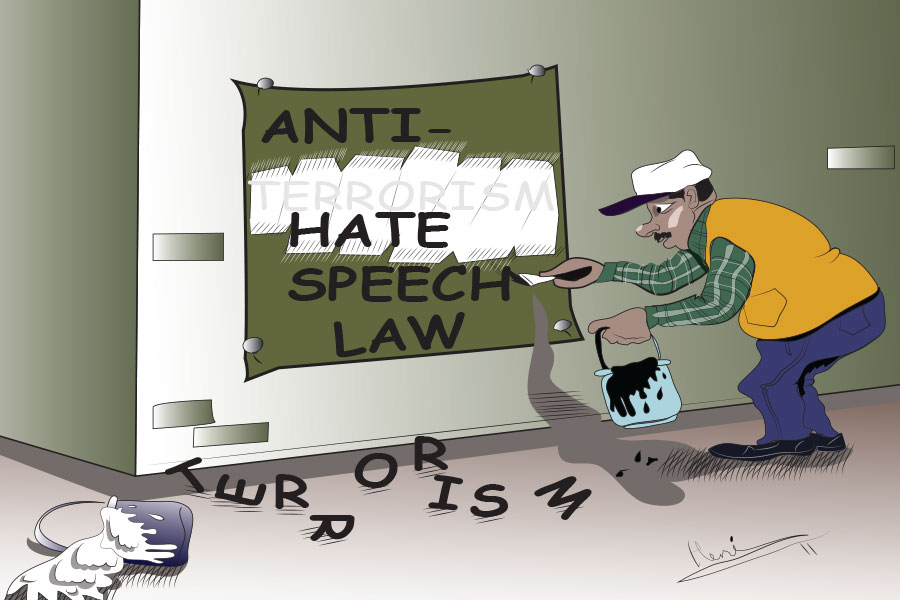

There are five major arguments raised in the editorial. One strand is that the draft proclamation to combat hate speech is comparable to or is some sort of replacement of the infamous anti-terrorism law. This is an over-simplistic assertion that hardly takes into account and totally neglects the glaring differences in the overall tone, approach, content and context of the two bills.

The anti-terrorism bill was adopted in a context when there was a clear and general tendency to restrict political freedom and space. The anti-terrorism proclamation was not adopted in isolation but alongside scores of other laws that were detrimental to freedom from the outset. The context we are in now is obviously quite different.

Just this week, we have learned that Ethiopia has improved dramatically in the 2019 issue of the World Press Freedom Index’s ranking published by Reporters Without Borders. A new and rights-friendly civil society organisation proclamation and a law that re-establishes and reinvigorates the National Electoral Board have already been enacted. A comprehensive and revised Media Act is in the pipeline.

Comparing the Ethiopia of the post-2005 election with contemporary Ethiopia and drawing a parallel between the anti-terrorism proclamation and the draft bill to combat hate speech will be doing a disservice to the genuine and concrete effort of the government to foster freedom and pluralism in a very challenging environment. Despite what the editorial implies, there is no reversal of course, and the government is still committed to its programme of political liberalisation.

The track record of the incumbent administration thus far is not a fluke accident. They emanate from a realisation and a conviction that as a nation, embracing individual liberty and pluralism is both a moral imperative and a practical necessity. The depth of this conviction shall continue to be demonstrated with further measures that will be taken including the enactment of a new and comprehensive Media Act that will institutionalise the freedom that the press is currently enjoying.

At this juncture, one might ask why the government is going through the trouble of adopting a hate speech bill, while the provisions of such bill could be incorporated in a new Media Act.

Why not wait?

The simple answer to this question lies in the fact that preparing a new draft Media Law in a participatory manner in which relevant stakeholders are involved is proving to be a very time-consuming process. Despite the effort on the part of the government, due to the technical complexity and difficulty of the task, adopting a comprehensive Media Act has taken several months and might not be completed for a few more months.

In the meantime, the urgency and gravity of the need for a law that addresses hate speech is becoming more and more apparent. Millions are displaced from their homes, too many lives have been lost and livelihoods have been destroyed. Too many have suffered and continue to suffer as a result of the avalanche of hatred and dangerous disinformation that has filled our social media feeds and that also seeps into our airwaves.

For a government to stand by and watch such tragedy unfold without doing everything in its power to fight such evil would be the height of irresponsibility. The road to mass graves and ethnic cleansings is paved by hate speech. Evil and hateful deeds are often preceded by evil and hateful words. We cannot and we shall not sit by and let this go on. We must act and we must act now. Every single day we continue to tolerate hate speech, we are risking irreparable harm to individual citizens because of their identity. Our social fabric has already been strained to the limit.

The editorial notes that “the true measure of free speech is the right to offend”.

I agree. As the European Court of Human Rights has opined in one of its most quoted dictums, “freedom of expression is applicable not only to ‘information’ or ‘ideas’ that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the state or any sector of the population”.

Nevertheless, we should not forget that the same court has stated that “[T]olerance and respect for the equal dignity of all human beings constitute the foundations of a democratic, pluralistic society. That being so, as a matter of principle it may be considered necessary in certain democratic societies to sanction or even prevent all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify hatred based on intolerance …, provided that any ‘formalities’, ‘conditions’, ‘restrictions’ or ‘penalties’ imposed are proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued”.

The court has also repeatedly pronounced its position that speech that is found to be “gratuitously offensive or insulting” could legitimately be proscribed. Thus, the maxim that free speech is a right to offend, shock or disturb should not be taken to mean that all sorts of offensive speech should be tolerated. Far from it, as the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights provides, states have an obligation under international law to prohibit hate speech by law.

This brings me to another claim in the editorial regarding the absence of a “single universally accepted definition of what hate speech is.”

It is true that there is not a universally accepted definition of hate speech, but this cannot lead to the conclusion that hate speech should be tolerated. There are many reprehensible and even criminal acts that do not have a universally accepted definition. The definition of what constitutes torture or genocide could be subject to debate, but this would not imply that we should refrain from prohibiting and punishing such acts.

There could be marginal differences in the understanding of what constitutes hate speech in various parts of the world. This difference arises out of the historical, political and social context of each country. But at the end of the day, the difficulty that arises out of these differences has not proven to be so insurmountable that it would make it impossible to criminalise hate speech. The experience of several countries is a testament to this fact.

In relation to this point, the editorial expresses a concern that the prohibition of hate speech that is provided within the draft law might be too broad and susceptible to abusive interpretation and application. This is a concern we take seriously. In preparing the preliminary draft, an attempt has been made to come up with a narrowly tailored law that is as clear as humanly possible.

Furthermore, taking into account the opinions and critiques we have received so far through various modalities, we have been revising the draft to enhance its clarity and avoid overly broad language. The penalties provided in the bill are also proportionate and some have even said lenient. The preliminary as well as revised draft also contains exemptions that are meant to minimise the chilling effect of the law on free speech and to protect those who provide sharp, shocking and even offensive political and social critiques.

After all, such a critique is an important and indispensable component of a democratic society. Far from targeting journalists, politicians and activists, the draft has provisions that are meant to shield them from the application of the law when they are engaged in political debate and criticism. What the law prohibits is speech that depicts as evil, demeans, threatens, encourages discrimination or attack against a person or an identifiable group or community on the basis of ethnicity, religion, race, gender, disability or such characteristics that are narrowly, explicitly and exhaustively enumerated.

Virtually all bloggers, politicians or journalists can freely express their views without engaging in such speech. For the sake of our collective survival as a nation, to uphold human dignity and the rights of others, and to avoid the catastrophic hate-fueled crimes we have witnessed in our country, it will not be too much to ask from our journalists, politicians and activists that they exercise some discretion when their speech refers to ethnicity or religion.

Finally, the editorial brings up political exclusion and economic inequality as the causes of hate speech and that the government should address these underlying factors instead of dealing with the symptom. This is not necessarily true.

African-Americans in the United States have been, and some will argue are still, subject to hate speech. Those who propagate hatred against African-Americans do so despite the fact that historically they have not suffered from political exclusion and economic inequality. The same is true with regard to anti-Semitism in Europe. It is not political exclusion and economic inequality that gave rise to the deadly anti-Semitism of the Third Reich.

Often, it is the victims of exclusion and inequality that are subjected to hate speech. The propagation of hate speech is another means that is employed by those who would like to perpetuate discrimination and exclusion. In fact, the attempt to tackle exclusion and inequality necessitates prohibition of hate speech. The continued proliferation of hate speech would make it impossible to do away with exclusion and inequality.

As a result, we should not tolerate hate speech - it will not be a sensible and prudent course of action. Tolerating hate speech will be tolerating those who sow the seeds of conflict, annihilation and destruction. We should ban hate speech and protect free speech by adopting a carefully crafted hate speech bill that should be applied with even more caution and circumspection.

Toward this end, all the feedback and comments received on the draft bill have been invaluable. The continued reform and strengthening of our judiciary and other actors in the justice sector will also be crucial. A hate speech law is not a silver bullet, but if adopted and applied with due care, it makes much better sense than a call for tolerating hate speech.

Let us protect free speech, by all means, but let us not tolerate the intolerable. History judges us for our cavalier attitude toward what is sacred and dear, the life and liberty of fellow human beings.

PUBLISHED ON

May 04,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

992]

Featured | Jan 08,2019

Editorial | Nov 16,2019

Films Review | Jul 27,2019

Life Matters | Apr 13,2019

My Opinion | Nov 14,2020

Radar | May 18,2024

Editorial | Apr 13,2019

View From Arada | Jul 20,2024

Editorial | Oct 02,2021

Radar | Oct 26,2019

My Opinion | 132105 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128507 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126435 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124046 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...