Editorial | Aug 28,2021

Apr 2 , 2022

By Mikael Alemu

Leo Tolstoy famously wrote that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. The great Russian writer would agree that all warring nations survive wars in their own ways as well. There are several vital facts about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that are notable.

The number of attacking troops is half of Russia’s armed forces and about 80pc of battle-ready troops. The operation’s objective is to topple the democratically elected and extremely popular (93pc support) government of the young Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and to destroy the armed forces and military industry of Ukraine. The Russian army is bombing civilian infrastructure in Ukrainian cities, and even hospitals and schools. The number of dead children is now in the hundreds.

The war is largely futile from a tactical perspective. Ukraine's mobilisation potential of two to three million people is much larger than Russian military force and reserves. It is also futile from a strategic point of view. An independent, proud, and unified nation of 40 million Ukrainians cannot be forced to live under Russian rule.

“A battle is won by the side that is absolutely determined to win,” Tolstoy wrote in ‘War and Peace.’ “Why did we lose the battle of Austerlitz? Our casualties were about the same as those of the French, but we had told ourselves early in the day that the battle was lost, so it was lost.”

From Ukrainian President Zelensky’s video address to British Parliament, his determination is palpable. The same cannot be said for Russia.

Worse still, the echo of war will sound for decades, if not centuries. The French invasion of Russia happened in 1812, but Tolstoy’s masterpiece about this war was written more than 65 years later. The echo of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will be heard for a long time and would be one of the forces that shapes the global world.

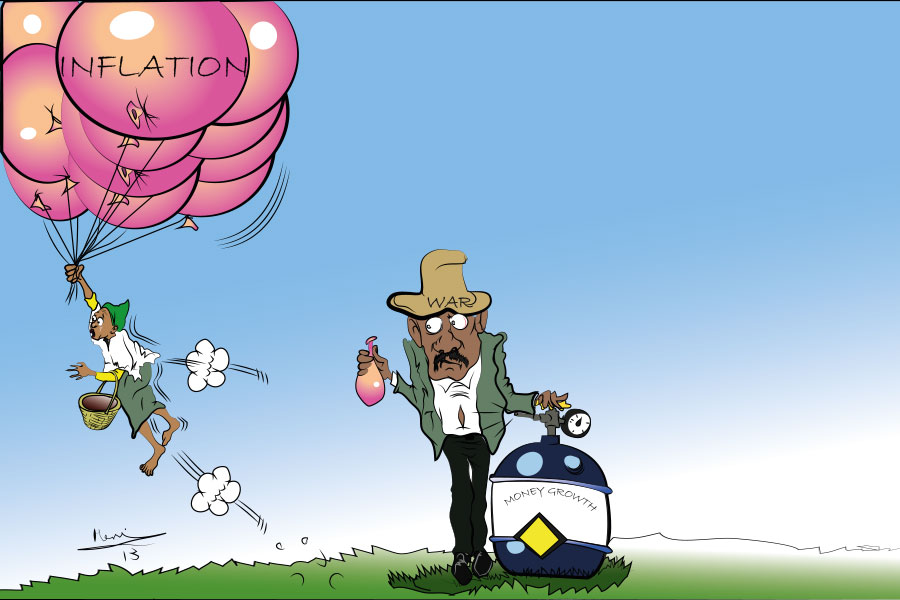

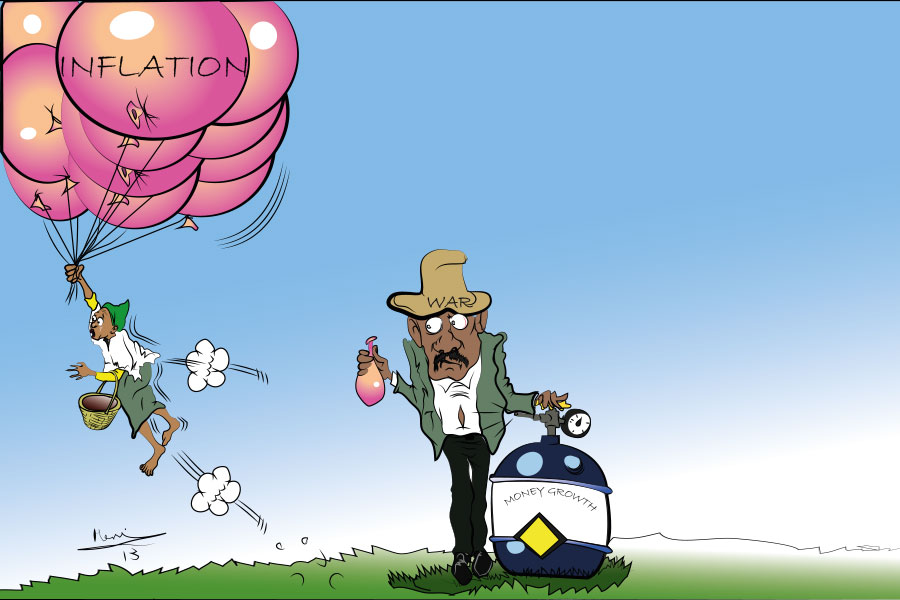

Part of the effect would be about global food and energy. Most observers say that African nations, including Ethiopia, will be most vulnerable, and this is certainly true.

But, as Tolstoy has written, “people are not able to judge what’s right or wrong. We have been eternally mistaken, and we will be mistaken.” It is critical to unpack the roots and causes of this crisis and identify our path forward.

Let us start with oil prices and availability. Russia is the third-largest oil producer in the world after the United States and Saudi Arabia. It provides 10pc of the world’s oil supply. There is no doubt that this will be changing: Russia is now heavily sanctioned and most of its banks are prohibited by the West from receiving foreign currency, and most shipping companies have cancelled their contracts to transport Russian oil.

The United States has already banned Russia from selling oil to US companies, and it is not unlikely that Europe will follow suit. This will have a serious effect on Russian economy as oil exports represent 15pc of GDP and 22pc of exports. The world, though, has several options to replace Russian oil, either by increasing oil production (Gulf countries can do this) or by reinstating Iran or Venezuela into the global oil market. There is no surprise that the oil prices that initially spiked after Russian rockets started to fall on Ukrainian territory are now back to February levels.

Another critical issue here is food prices. Ukraine and Russia are both major exporters of some of the world's most basic foodstuffs. The two countries together account for 29pc of global wheat exports, 19pc of world corn supplies and 80pc of world sunflower oil exports.

Ukrainian agriculture and agro-processing are obviously in ruins and will take at least two to three years to recover, while Russia is sanctioned and most likely will not have access to shipping lines for the coming decades. One should expect that both countries will ban exports of the foodstuff following the war.

It is not possible to shift agriculture production to other countries, so we will not see new substantial sources of wheat, corn and sunflower oil this year, or the next. Reduced supply will drive prices up, and this is inevitable. An important side note is that as the food deficit grows, many countries will ban exports of their produce, and supply will reduce even further. We should remember that food supply can be used as a political weapon, so country-specific embargos are to be expected.

One shall understand that the global food market will be turbulent for the next five years. New dominant players will emerge, new alliances will be forged and new routes will evolve. The only smart strategy is to follow the trends, be opportunistic, build and keep reserves.

The matter of food will be much more pertinent to Ethiopia than oil. A quarter of all wheat and most of the sunflower oil in Ethiopia is imported. On the other hand, wheat is not the prevalent crop and sunflower oil only makes up a fifth of edible oil that the country consumes. Food supply from warring regions is not critical for Ethiopia: imports from Russia are almost non-existent and imports from Ukraine are not substantial.

Let us also not forget fertiliser prices and availability. Russian war in Ukraine affects the fertiliser industry in a big way. Not only Russia but its sidekick Belarus is sanctioned. Both are major exporters of fertilisers in the global market, at first and seventh place, respectively. Russia accounts for nearly a quarter of global exports of ammonia, a key ingredient in nitrogen fertilisers, 14pc of global urea exports, and 14pc of mono-ammonium phosphate (MAP) exports. And both Russia and Belarus each account for about a fifth of potash exports. The former’s natural gas is a major component of fertiliser production in some European countries.

It is no surprise then that the spot market for fertilisers looks crazy these days, especially with Russia upping the ante by suspending exports of the commodity. On the bright side, the fertiliser market is very seasonal and the demand will peak much later. There are also substantial reserves in fertiliser products that can help balance the market: several major companies can restart the production and eliminate the deficit of fertilisers.

Ethiopia does not import fertilisers from Eastern Europe but from Morocco and other countries in Africa and the Middle East. Therefore, no logistical challenges are to emerge. Of course, since prices are set in global markets, it will be costly to import.

Taken together, I do not share the panic reaction to the Russia-Ukraine crisis. The sanctions against Russia will not lead to a catastrophic outcome for global food security or energy. We may expect the global markets to adjust to the new configuration within one to two years. Ethiopia will be one of the least affected countries in terms of logistics as our trade with Russia is minimal.

On the other hand, Ethiopia is extremely vulnerable to global prices for almost anything: from wheat to oil to fertilisers. This circumstance cannot stand, and we shall treat today’s crisis as a wake-up call. There is no alternative to food security and energy security. Ethiopia is endowed with vast and fertile lands, rich natural resources, and exceptional opportunities. Our farmers can grow more wheat and produce much more edible oil. Ethiopia has to explore its deposits of potash and build a strategic reserve for other fertilisers. Ethiopia can also switch from diesel-generated electricity to off-grid solar and other renewable sources, thus eliminating 35pc of fuel imports.

The Ethiopian business community can collaborate with the government to create a detailed strategic plan of practical steps necessary to achieve food security and pull substantial resources to this goal.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 02,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1144]

Editorial | Aug 28,2021

Radar | Jul 28,2025

Viewpoints | Oct 07,2023

Fortune News | Feb 01,2020

Radar | Dec 25,2023

Commentaries | Jul 18,2020

Fortune News | Sep 30,2023

Fortune News | Jan 18,2020

Radar | Jul 18,2021

Viewpoints | Jun 18,2022

Photo Gallery | 175339 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165564 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155890 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136808 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...