Viewpoints | Dec 30,2023

May 13 , 2023

By Daniel Gros

If one measures the impact of inflation on households at various income levels, adjusted for their group’s consumption patterns, one does find some cases where the effective inflation rate for the lowest-income quantile is several percentage points higher than it is for the wealthiest quantile. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in poorer countries, argues Daniel Gros, a director of the Institute for European Policy-Making at Bocconi University.

Economic policymakers worldwide have struggled to stem rising inequality – a trend that has impeded economic growth, fueled populist electoral victories and jeopardized liberal democracy. It was thus widely and understandably feared that unskilled workers would suffer deeply due to the COVID-19 crisis and, more recently, the energy-price shock that followed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

But, in both cases, the impact has been relatively benign.

After the initial pandemic shock in early 2020, economies and job growth rebounded strongly. Thanks to the robust recovery and far-reaching government support programs, income inequality fell by most measures, especially in the United States (US), owing to substantial cash transfers to households, but also throughout Europe, where government income support was more moderate.

However, another shock arrived before the pandemic recovery was complete: Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and energy prices spiked. But not all energy shocks are created equal. Whereas in the past, they were driven largely by crude oil prices – which peaked immediately after the invasion but are now in line with the pre-war average – natural gas is today’s main problem.

While natural-gas prices have fallen from their post-invasion peak in the summer of 2022, they remain two to three times higher than the pre-2021 average.

This is not a problem for the US. On the contrary, as a (small) net exporter of natural gas, the US has benefited from the energy-price shock, as its terms of trade have improved (export prices have increased by more than import prices). As a result, the country, in the aggregate, can consume more.

But while high gas prices have made the US slightly richer, they have made Europe substantially poorer. Because Europe imports most of its natural gas, consumers and firms are still paying significantly more for energy than before the war, and the eurozone’s terms of trade have deteriorated, implying an income loss of close to two percent of GDP.

With wage growth lagging behind inflation, real wages have fallen sharply throughout Europe (they have remained roughly constant in the US), creating the impression that inequality has increased. But the average values might be misleading. After all, wage growth is not necessarily consistent across income groups, and the inflation rate, as measured by the consumer price index, does not reflect differences in cost-of-living fluctuations across the income distribution.

Lower-income households spend a larger share of their budget on energy across and within countries than their high-income counterparts. In Romania – one of the European Union’s poorer members – energy and food account for 25pc of all consumption expenditure, compared to 13pc in much wealthier Germany. At the same time, the bottom quintile of the income distribution within Germany spends more on non-transport energy (eight percent) than the top quintile (five percent). This means that when energy prices increase, the official inflation rate might understate the extent to which poorer households lose purchasing power.

But other forces might offset the increase in energy costs. For example, poorer households tend to rent, rather than own, their residences, and rents have increased more slowly than the overall price level.

Such effects do not necessarily fully offset increased energy prices. If one measures the impact of inflation on households at various income levels, adjusted for their group’s consumption patterns, one does find some cases where the effective inflation rate for the lowest-income quantile is several percentage points higher than it is for the wealthiest quantile. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in poorer countries.

But there are also cases where low-income households have suffered a smaller loss in purchasing power than wealthier households. This is the case in Germany, where home ownership is less common, and in France, where household energy prices have been kept low. Since these two countries account for a significant share of the eurozone economy, the average difference between the purchasing-power losses suffered by the richest and the poorest households in the eurozone is small.

Moreover, in the US and some European countries, wages are increasing faster at the bottom end of the income distribution – what in the US has been called “unexpected wage compression”. In Germany, unskilled employees’ wages have increased by about eight percent over the last year, while senior specialists or executives have secured increases averaging less than two percent.

Observers are not wrong to highlight the hardship that the pandemic and the Ukraine war have wrought for many poorer countries and households, some of which struggled to keep warm this winter. But average figures and blanket statements fail to account for important differences across income groups, not least the disproportionate increase in income gains for those at the bottom of the distribution.

PUBLISHED ON

May 13,2023 [ VOL

24 , NO

1202]

Viewpoints | Dec 30,2023

Editorial | Sep 27,2025

My Opinion | Mar 26,2022

Viewpoints | Jun 27,2020

Commentaries | Dec 19,2021

Fineline | Jan 15,2020

Commentaries | Jan 13,2024

Commentaries | Jun 11,2022

Life Matters | Sep 11,2020

Commentaries | Jul 20,2019

Photo Gallery | 175247 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165471 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155781 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136789 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

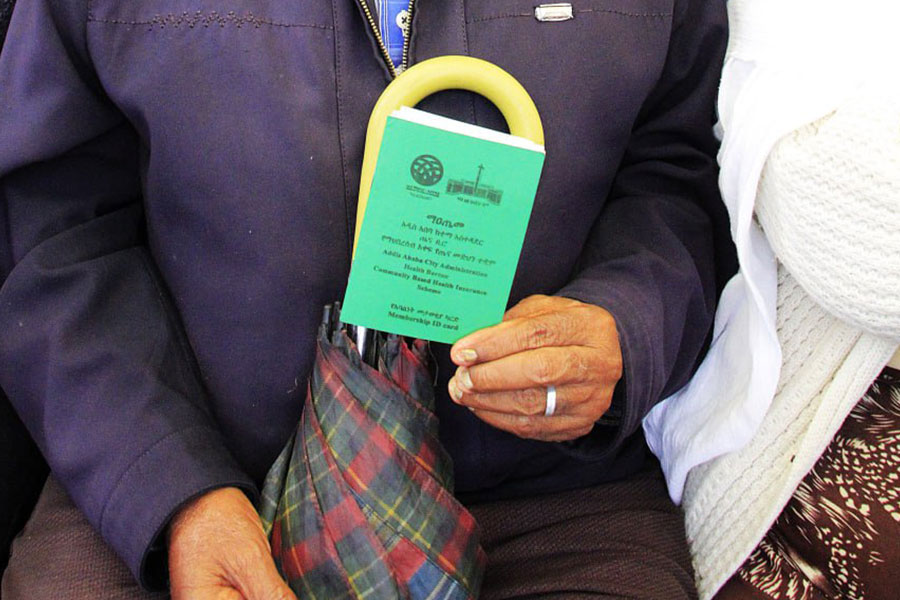

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...