Jan 2 , 2021.

One by one, Workneh Gebeyehu (PhD), executive secretary of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), welcomed heads of state and dignitaries from the Horn of African countries on December 20, 2020, in the capital of Djibouti. Eritrea's strongman, Issayas Afeworqi, was the unsurprising exception. Ever the recluse, the 38th assembly of IGAD heads of state and government commenced in the usual absence of Eritrea, despite its recent assertiveness on Horn politics.

In a large hall adorned by each country's respective flags, statements were made and well wishes exchanged. In many regards, it was a master class in tiptoeing around significant issues that would doubtlessly lead to differences of opinion and confrontations. The communiqué produced following the summit demonstrated this.

Sudan was “commended” for its attempts to transition to democracy and congratulated for being de-listed from the United State's list of countries supporting terrorism. South Sudan was “appreciated” for resuming peace talks, as well as Somalia for combating Al-Shabaab and praised for holding talks with Somaliland. The big news in Ethiopia following the summit was the reaffirmation given by the assembly for what it considered the need to ensure the “primacy of constitutional order, stability and unity” of the country through the militarised conflict in Tigray Regional State. The sentiment was echoed by Moussa Faki Mahamat, head of the African Union Commission, who was also in attendance.

For those who were keen in following the affairs of IGAD and its members, it was one of the strangest summits ever held since 1984, when IGAD was the Intergovernmental Authority on Drought & Development (IGADD). Unable to conceal their estrangement toward each other, the heads of state (or their representatives) gathered in an assembly that failed to call attention to the concerning confrontations between the member states. Some of these have newly erupted. Ethiopia has just seen an all-out armed conflict, the state of which is not clear and remains concerning.

With its western neighbour Sudan, there is a confrontation over border issues that cannot be overlooked. It has left causalities, with both sides accusing one another of aggression. Despite talks being held to resolve the matter, there does not seem to be enough to indicate that an agreement is being reached. Sudan has made its moves in changing the status quo on the ground, perhaps wanting to push Ethiopia to international arbitration, knowing that it could easily win its case.

To the north, Eritrea's involvement in the military conflict in the Tigray region becomes no longer a subject of claims and denial. Addis Abeba remains mute in the face of relentless coverage by the international media of Eritrea's role in the conflict.

Reads a headline in a recent edition of The Economist: "Evidence mounts that Eritrean forces are in Ethiopia."

It is only one among several stories appearing almost daily exposing Eritrea's meddling in Ethiopia's internal affairs, its arch foe for over two decades. It also has unresolved issues with Sudan, both accusing one another of harbouring armed opposition groups. Border issues that caused a military confrontation in 2008 remain unaddressed. Eritrea is at odds with Djibouti, due to issues from a border conflict left unresolved for more than a decade.

No less alarming is the diplomatic row between Somalia and Kenya. Long a troubled country marred by violence, Somalia withdrew diplomats from Kenya and told those of its neighbour to leave. Uganda is embroiled in its elections debacle, where a pop singer forced the worst in Yoweri Museveni to come out.

The state of affairs in the Horn of Africa region has arguably never been this dire.

Yet the communiqué IGAD issued at the end of the summmit has failed to acknowledge that these problems exist, let alone suggesting the assembly tried to find a way of dealing with them. For a region rife with political challenges, home to perennial conflicts, it did not bring up in any meaningful way the lack of national political settlement many of the countries face. Indeed, any attempt to call attention to the internal political problems being faced – such as those of Ethiopia – would have opened a Pandora's Box to a body whose member states are at best quasi-democratic (Kenya), at worst downright authoritarian (Djibouti), and some totalitarian in the case of Eritrea. It is an issue that has been avoided ever since IGAD's founding.

In the wake of a devastating famine in Ethiopia, with an estimated death toll of over a million people, and in Sudan, IGADD was established. Until Eritrea’s and South Sudan’s independence and entry into the organisation, six members formed IGADD considering the prevailing challenges of their time. It was convenient in creating a platform over an issue many were in agreement over - addressing food insecurity.

That body was restructured into IGAD in 1996, which expanded its mission but safely within the sphere of development and economic integration. Tellingly, it does not see democratisation and political settlement among its objectives. It does spell out the need to promote “peace and stability,” but that is a long way off from democracy.

There too, unfortunately, the assembly disappointed. It was short of articulating a vision on how the bridge should be crossed for a sub-continent facing chronic food insecurity, economic slowdown and political challenges.

The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) was brought up, but with lacking enthusiasm. Outlines to a regional response to COVID-19 were endorsed and received support from the European Union. Commendably, the assembly agreed to lobby for an equal distribution of vaccines to its member states. But the challenge COVID-19 poses to economic development, which has thrown most of the world into a recession, was glossed over. Most importantly, this has to do with food insecurity. Even before the pandemic, nearly 17 million people were expected to face severe food insecurity in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan.

In the whole of East Africa, there are some 41 million people expected to become food insecure as a result of the pandemic.

The desert locust will exasperate this. The United Nations projects that Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Kenya are expected to see a resurgence of desert locust swarms. They have already left a million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Ethiopia. Somalia declared a national food emergency earlier in 2020 as the locusts massed ahead of the April harvest.

Such matters requiring humanitarian responses did not go unmentioned, but neither has there been an agreement on a clear way forward. The furthest the heads of state have gone was to endorse a disaster response fund proposed for establishment back in 2013. Considering the challenge faced and the recurrent natural disasters expected to occur as extreme climate conditions arise, this is a weak place to start from. They are leaving themselves with barely any tools or plans to fight against oncoming challenges.

Clearly, this is a group of governments facing unprecedented challenges at home and lacking the institutional capabilities to address conflicts that occur within and between them along their borders. Their priorities are all over the place and have long preferred to deal with their differences bilaterally. If they could, they have attempted to use institutions such as the African Union against one another, not as platforms of negotiations and settlement. Neither is the African Union (AU) and institution with leaders who can step up to the plate. Its Chairman, Moussa F. Mahamat, has proven to be a complete disappointment even by his predecessors' lowest standards.

The advantage of IGAD has been its promise to create a collective foundation for development between the countries of upper East Africa, independent of outside players' interests. It could do this without the much larger cumbersomeness - in terms of membership and objectives - of the African Union. IGAD could have gotten a useful lesson from its sister organisations in SADC and ECOWAS.

Unfortunately, when suspicion among leaders reigns high and pressing challenges are avoided to pass messages of appreciation and congratulations, IGAD remains unable to gain relevance to 230 million people subjected to violence, displacement, hunger, and unbearable human rights abuses when they run away from their native lands. IGAD's promise of food security, peace and security, and economic integration can only be realised when the rotating chairpersons exercise proper leadership, and the body can serve as a platform for addressing challenges that run through the countries’ porous borders.

The current chair, Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, has failed the suffering millions in the sub-region, as many of his predecessors had.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 02,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1079]

Radar | Sep 27,2025

Radar | May 12,2024

Fortune News | Jul 21,2024

Fortune News | Nov 05,2022

Radar | Sep 26,2021

My Opinion | Nov 21,2018

My Opinion | Aug 27,2022

Radar | May 02,2020

Commentaries | May 11,2024

My Opinion | Apr 29,2023

Photo Gallery | 174132 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164355 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 154481 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136632 Views | Aug 14,2021

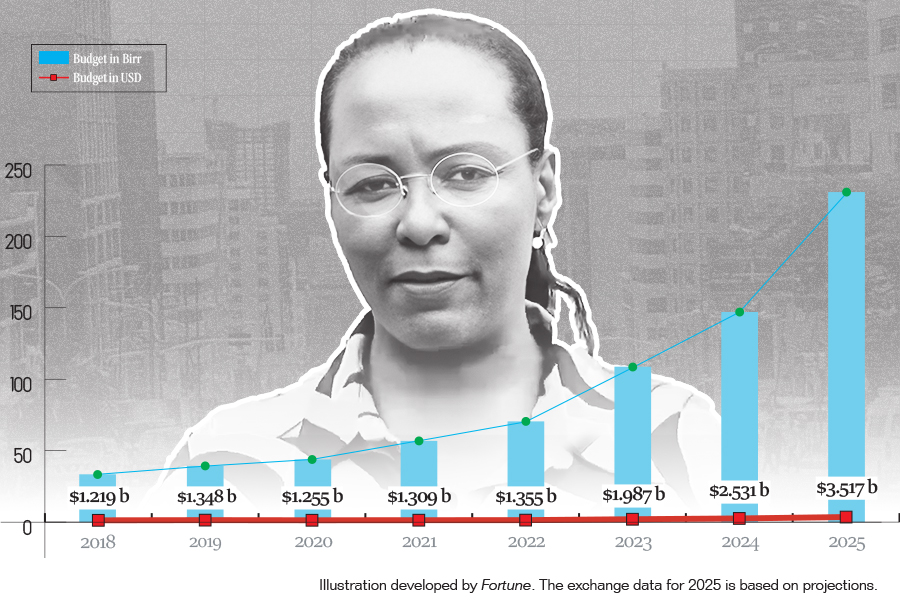

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...