Viewpoints | Aug 10,2024

Dec 24 , 2022

By Bjorn Lomborg , Jordan B. Peterson (PhD)

There is little difference between having 169 goals and having none. We have placed core targets such as eradicating infant mortality and providing basic education on the same footing as well-intentioned but peripheral targets like boosting recycling and promoting lifestyles in harmony with nature. Trying to do everything at once, we risk doing very little, as we have for the last seven years, write Bjorn Lomborg (PhD), president of the Copenhagen Consensus and visiting fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, and Jordan B. Peterson (PhD), a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto.

We traditionally reflect on the consequences of our past behaviour during the end-of-year holidays and contemplate the good to achieve in the 12 months ahead. When we set resolutions, we strive to determine how we can do better in our own lives. Perhaps we could also take the occasion to consider how we might achieve such improvement on a larger scale.

In 2015, the world's leaders attempted to address the major problems facing humanity by establishing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) – a compilation of 169 targets to be hit by 2030. Every admirable pursuit imaginable made the list: eradicating poverty and disease, stopping war and climate change, protecting biodiversity and improving education.

In 2023, we are at the halfway point, given the 2016-2030 time horizon, but we will be far from halfway towards hitting our putative targets. Given current trends, we will achieve them half a century late.

What is the primary cause of our failure?

There is little difference between having 169 goals and having none. We have placed core targets such as eradicating infant mortality and providing basic education on the same footing as well-intentioned but peripheral targets like boosting recycling and promoting lifestyles in harmony with nature. Trying to do everything at once, we risk doing very little, as we have for the last seven years.

It is long past time to identify and prioritise our most crucial goals. With several Nobel laureates and more than 100 leading economists, the think tank Copenhagen Consensus has done precisely that, identifying where each dollar can do the most good.

We could, for example, hasten an end to hunger.

Despite significant progress over the past decades, more than 800 million people still go without enough food. Careful economic research helps identify ingenious and effective solutions.

Hunger hits hardest in the first 1,000 days of a child's life, beginning with conception and proceeding over the next two years. Children who face a shortage of essential nutrients and vitamins grow slowly, both physically and intellectually. They will attend school less often, achieve lower grades, and are poorer and less productive as adults.

We can effectively deliver essential nutrients to pregnant mothers. The provision of a daily multivitamin or mineral supplement costs a bit over two dollars for a pregnancy. This helps babies' brains develop better, making them more productive and better paid in adult life. Each dollar spent would deliver an astounding 38 dollars of social benefit.

Why would we not first take this path?

Because in trying to please everyone, we spend a little on everything, essentially ignoring the most effective solutions.

Consider, as well, what we could accomplish on the education front. The world has finally managed to get most children into school. Unfortunately, the schools are often of low quality, and more than half the children in poor countries cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Typically, schools have all 12-year-olds in the same class, although they have very different levels of knowledge. No matter which group the teacher teaches at, many will be lost and others bored. Let each child spend one hour a day with a tablet that adapts teaching to that child's level. Even as the rest of the school day is unchanged, this will, over a year, produce learning equivalent to three years of typical education.

What would this cost?

The shared tablet, charging costs, and extra teacher instruction cost about 26 dollars for a student over a year. But tripling the learning rate for just one year makes each student more productive in adulthood, enabling them to generate an additional 1,700 dollars in today's money. Each dollar invested would deliver 65 dollars in long-term benefits.

When we fragment our attention and try to please everyone, we implement superficially attractive but inefficient policies. Along with hunger and education, there are about a dozen other incredibly effective policies, such as drastically reducing tuberculosis and corruption. Those are targets we could and should hit. The moral imperative is clear: we must do the best things first.

There is a resolution, both personal and social. That is the pathway forward to a better future. Let us resolve to walk down that road as we consider the dawning of the new year.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 24,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1182]

Viewpoints | Aug 10,2024

Radar | Aug 13,2022

Fortune News | Oct 21,2024

Fortune News | Jan 21,2023

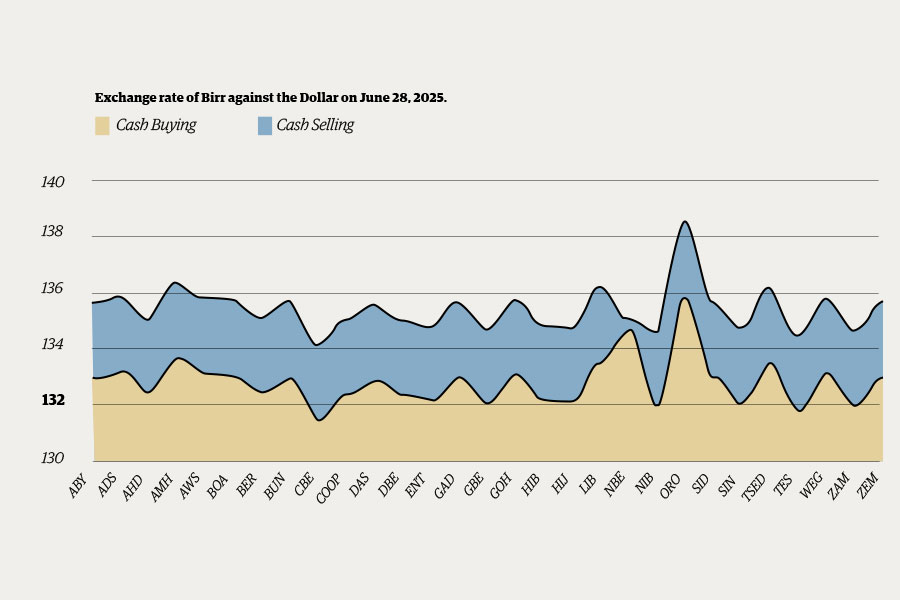

Money Market Watch | Jun 29,2025

Editorial | May 06,2023

News Analysis | Nov 03,2024

Life Matters | Jul 17,2022

Radar | Jul 17,2022

Viewpoints | Sep 16,2023

My Opinion | 132038 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128435 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126362 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123981 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...