Sunday with Eden | Mar 28,2020

May 16 , 2020

By Tesfaye Yehualashet

The very idea of convening the 2020 election has been a bone of contention since the assumption of the premiership by Abiy Ahmed (PhD) two years ago. The appetite on the side of the government to hold an election was exceptionally low from the beginning, and it has been dragging its feet when it could have been making up for lost time.

The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is the final nail in the coffin of an election that may not have ever happened in the first place.

In order to address and limit the damaging leadership vacuum at the federal and regional level, options had been tabled by the government for postponing the election. These included the dissolution of parliament, the state of emergency decree, a constitutional amendment or interpretation by the House of Federation. The latter has been voted by parliament as the best way forward.

The parliament was wrong to do this, nonetheless. None of the options, in fact, meet the criteria for a constitutional way out of this conundrum.

Take the state of emergency declaration. This would have been both undesirable and dangerous mainly because the grounds for declaring a national emergency are an external invasion, a breakdown of law and order that endangers the constitutional order and cannot be controlled by the regular law enforcement agencies, a natural disaster or an epidemic.

The expiry of the term of office of members of parliament are not grounds for declaring a SoE. It can also be argued that this article cannot be invoked with the assumption that one of those conditions necessitate an extension to the term of parliament. That is not what the Constitution stipulates. The option of dissolving parliament also suffers from the same fate, since extending the time in office of the incumbents was never what it was meant for.

The constitutional amendment option is no less unlikely. For some, amending the Constitution, particularly those provisions that require relatively less stringent amendment procedures can be secured. But to initiate an amendment, any proposal for constitutional amendment should be submitted “for discussion and decision to the general public.”

Given the very justification for the postponement of the election, this would be absurd. The National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) has said that it would not be able to meet the logistical needs to hold the election as a result of lockdowns here and abroad. Another reason for not holding the election has been that campaigning and voting would require large public gatherings. Thus, by the same logic, public consultations could not be acceptable.

There is also the matter of members of both the upper and lower legislative houses being agents of the “nations, nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia," and an attempt to amend the Constitution to extend their term of office poses a clear conflict of interest.

This brings us to constitutional interpretation. The House of Federation is mandated to provide an authoritative interpretation of the Constitution. But this also has limitations.

The House does not involve itself in abstract review, and if it could it would have been made clear in the Constitution. Its mandate is limited to when a constitutional dispute is submitted. Until now, no formal constitutional dispute has been submitted and cannot be triggered in this scenario.

Constitutional interpretation in this matter would also involve creating new laws. Hence, where there is no dispute that has formally been submitted, constitutional interpretation is not only a hypothetical academic exercise but also an attempt to create new provisions out of thin air.

What other alternatives are there then?

We can consider strengthening and mandating the House of Federation. Institution building is a continuous process, and crises like these are excellent reminders of the central role of strong, independent and dynamic institutions. To minimise the damage of the looming legitimacy crisis, strengthening and mandating the House of Federation would be an area to consider for the following constitutional changes.

All sovereign power resides in the “Nations, Nationalities and Peoples of Ethiopia,” and the Constitution is an expression of their sovereignty. The House of Federation is composed of the representatives of these sovereign entities, and each “Nation, Nationality and People” shall be represented in the House of the Federation by at least one member and by one additional representative for each one million of its population.

Even though the term of mandate of the House of the Federation is five years, members of the HoF can be elected by the State Councils themselves. This presents an opportunity. The Councils could thus nominate members of the HoF before the term of their respective State Councils expire. This will not only serve to minimise the damage as a result of the legitimacy crisis but also preserve a functioning institution in case a constitutional dispute emerges.

This unavoidably presents a great deal of problems and sets a dangerous precedent. The biggest obstacle would be that it is not apparent from the Constitution if the authority of every single member of the Federation expires, no matter their time in office, once a single term of the House is finished. However, especially considering the options presented by the government, it would not hurt to consider this option.

The government could also explore holding elections by regional states.

The Constitution prescribes the establishment of a National Election Board independent of any influence, to conduct in an impartial manner free and fair elections in “Federal and State constituencies.”

The reference to federal and state constituencies can be interpreted to mean that it refers to election constituencies that are held to parliament and not to the state councils.

The best argument for this is that the Constitution assumes regional states can establish similar regional election institutions. We can see this from Article 47 on the right of any “Nation, Nationality and People” to form its own right.

It is stipulated that “the Council that received the demand [for statehood] has organised a referendum within one year to be held in the Nation, Nationality or People that made the demand.”

This assumes that regional governments should be able to hold elections to their own state councils. This can be considered to limit the damage to the legitimacy crisis. The room for experimentation the federal system provides should be leveraged to hold regional state-level elections.

We also need to consider the role to be played by the President, which is the Head of State, elected by a joint session of parliament and the House of the Federation by a two-thirds majority vote, with a term of office of six years. After the expiry of the term of parliament, including the Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, entrusting the President to conduct the day-to-day affairs of government and organising new elections, without enacting new proclamations, regulations or decrees, or repealing or amending any existing law, may be explored as a political compromise.

Of course, these propositions are not foolproof, but it is a tragedy that they are not being considered. The looming legitimacy crisis should be addressed comprehensively both at the federal and regional levels, with an authoritative course of action with an adequate focus on strengthening existing institutions, to limit potential consequential damages.

PUBLISHED ON

May 16,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1046]

Sunday with Eden | Mar 28,2020

My Opinion | Oct 11,2025

Commentaries | Apr 15,2023

Commentaries | Aug 05,2023

Fortune News | May 13,2023

Commentaries | Mar 18,2023

Commentaries | Jul 10,2021

Verbatim | Jun 17,2023

Viewpoints | Apr 19,2025

Fortune News | Oct 21,2023

Photo Gallery | 174868 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165088 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155350 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136738 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

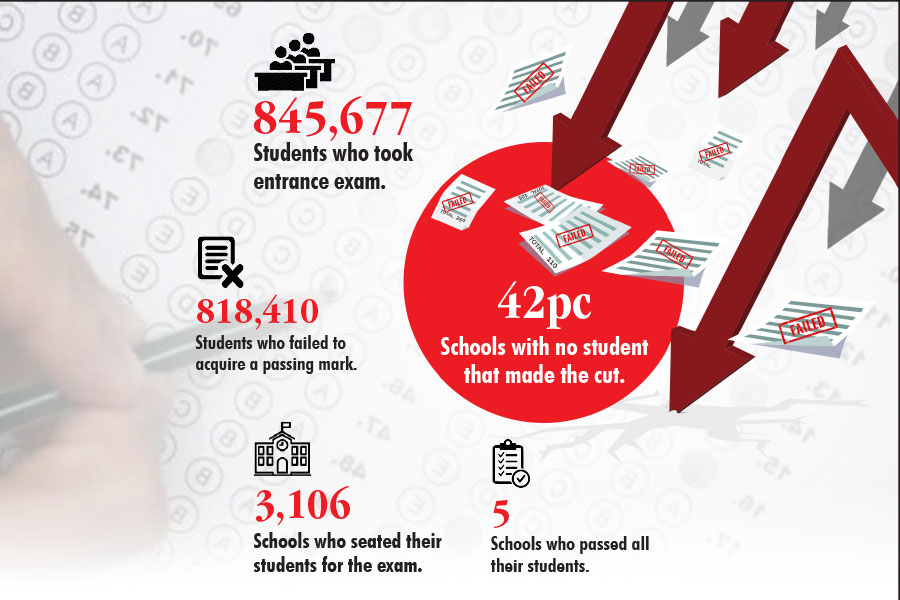

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...