Viewpoints | Jun 05,2021

Aug 1 , 2020

By

My active involvement in Ethiopia’s politics started with the popular movement that led to the ousting of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974 and ended in 1983 when I was released from my last imprisonment by the Dergue.

But I have been following the politics of the last couple of years as a citizen of the country with a great sense of hope and despair. One can almost say that I was part of what is broadly known as the “silent majority.”

The recent assassination of Hachalu Hundessa, political activist and musician, and the subsequent political unrest that was witnessed across the country has shocked me out of my state of silence. While the sad events of recent weeks are part of a worrying pattern of the last couple of years, this political madness is a sad consequence of the misguided politics that was promoted in the country since the 1960s.

Over the years, numerous attempts have been made by analysts and researchers to identify the problems and prescribe solutions. Most of these efforts end up by proposing simplistic solutions based on partial consideration of the factors that determine the political dynamics of the country. As part of this simplification, some of these analyses conclude by blaming one or another political group or even a generation for the state of politics in the country.

But there is a deep-rooted malaise that has not been uncovered by the reductionist frame of analysis followed by most analysts and writers. As has been proven in other fields of study, deploying the reductionist approach to understand complexity can only lead to incomplete solutions based on a partial understanding of the dynamics. One can only overcome such limitations by utilising systems thinking as the basis.

There is thus the need for understanding and resolving the complex situation of Ethiopia from a systems dynamics perspective. To do this, we will have to first look at the fundamental malaise of Ethiopia’s politics from a systems thinking perspective.

What comprises this malaise?

While recognising that there could be several contributing factors to the problem, it is possible to identify the following fundamental issues in our politics from a systems perspective.

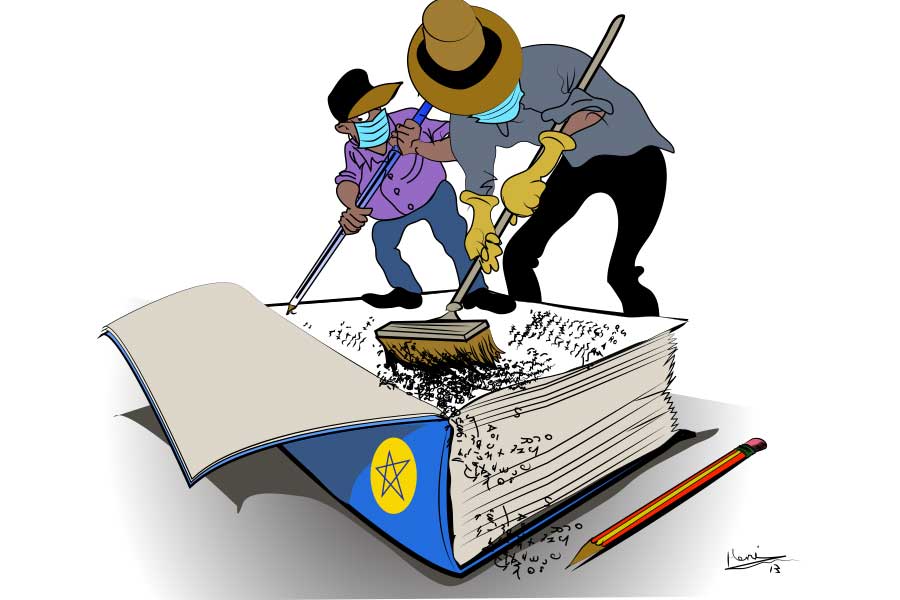

Primary of these is incidental leapfrogging. Ethiopia’s politics in its modern sense is associated with the introduction of modern education, particularly university education. One of the significant limitations of the current modern education is its disconnect from the indigenous knowledge system and the specific need and context of the country both in terms of content and delivery.

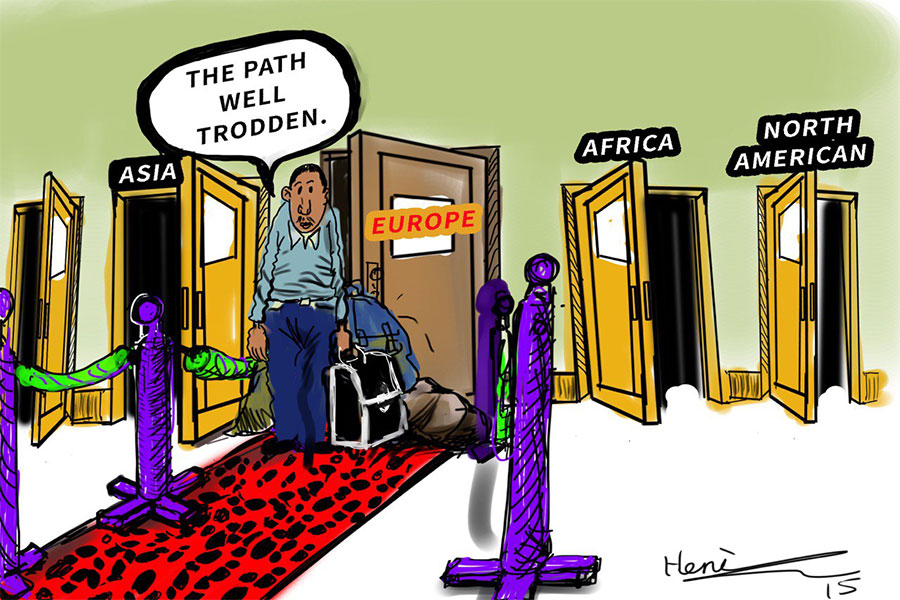

As a result, it largely propagated the creation of an educated elite that has become a wholesale believer of stereotype modernity rather than being a solution provider to societal problems. The same ailment has been witnessed in Ethiopia’s modern politics. As a result, Ethiopia’s politics since the 1960s is characterised by wholesale buy-in of political philosophies and models that are neither compatible with the socio-cultural foundation nor responsive to the specific context and need of the country.

This trend seems to be dominant in the programmes and policies of many political parties to this day. There is no doubt about the critical benefit of learning from experience and knowledge of other countries and communities. However, experience from countries that have been successful in such an exercise over the last 70 years has shown that it is very critical to adapt this knowledge and experience to the specific context of the country.

Another of these fundamental maladies is what I am going to refer to as a feudal political psyche. Even if modern politics in Ethiopia started to emerge within the last century, the country has a long history of state politics and traditional governance practices. This includes deep-rooted and effective traditional governance and conflict resolution practices that have some embedded democratic ingredients.

But we also have more repressive political machinations carried over from the feudal era that are mainly characterised by different forms of palace intrigue and political repression. Unfortunately, the primary proponents of party politics in Ethiopia, who pledge in the name of democratic principles, have never been able to shed the residual mindset of the feudal politics of the past.

As a result, most of the leading political parties of the 1970s ended up promoting political serfdom instead of political liberty even within their organisations – this includes absolute and unquestionable loyalty to the leadership of the political movement. The culture of destructive engagement, which includes character and physical assassination that has been dominant in our politics, is associated with these deep-rooted residues of feudal politics in our political psyche.

Indeed, until recently, our modern party politics have shown total disregard and disdain to the positive and democratic elements of traditional governance systems and practices. In recent years, we have witnessed the emergence of young political and community leaders who are relatively free of such political servitude. However, we need to make every effort to protect these new generations of leaders from the suffocating effect of the elitist political culture that is deeply rooted in the feudal political psyche.

Reductionist analysis that is widely utilised in our political discourse is another deep-rooted problem we have. Reductionist simplification, which forms the epistemological foundation of modern education, has been highly instrumental in the impressive development of science and technology of the last two centuries. Since the middle of the 20th century, however, its limitation in understanding more complex economic, social, environmental and political issues and generating solutions has become increasingly evident.

Numerous efforts that have been made by many political analysts and intellectuals to identify the problems and provide solutions to Ethiopian politics through the reductionist lenses have miserably failed. This is because reductionism has inherent methodological limitations for understanding complex problems. Systems thinking is a trans-disciplinary science that emerged since the middle of the 20th century to deal with complex issues from a systems dynamics perspective.

It is based on the premises that understanding the dynamics of a given complex system from a holistic perspective is key for managing it effectively. Even if it is considered as the science of the 21st century, systems thinking resonates very well with some of the common principles of indigenous knowledge systems.

In this context, our political leaders, intellectuals, activists and media personalities need to refrain from advocating for simplistic solutions based on a reductionist analysis and tap into their potential to become a transformational leader guided by systems thinking.

Finding the antidotes for the critical illness of our politics based on systems analysis is the first key step for building a stable and prosperous democratic society. Such transition requires the collective and collaborative involvement of all stakeholders, rather than being left for political leaders.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 01,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1057]

Viewpoints | Jun 05,2021

Editorial | Feb 25,2023

Editorial | Sep 27,2020

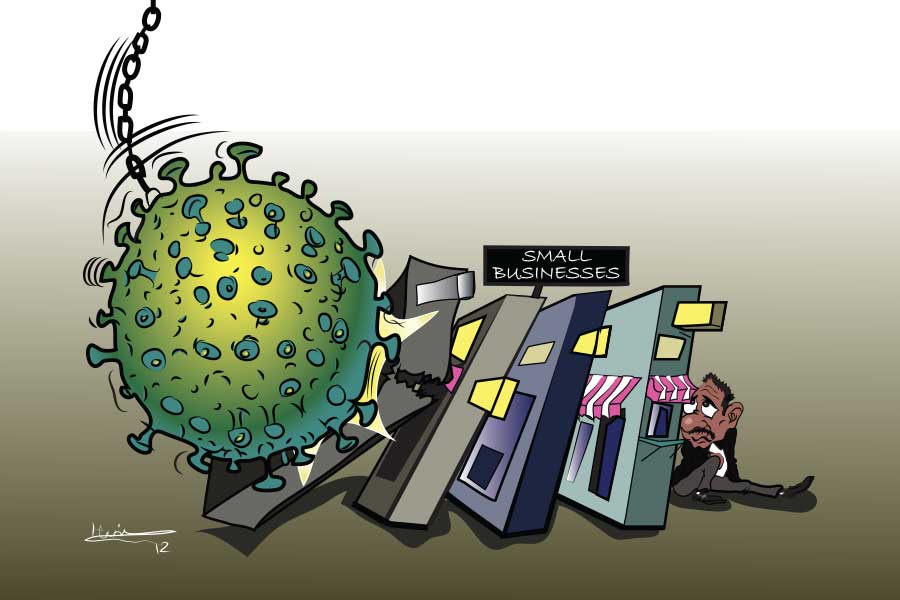

Editorial | Apr 04,2020

Viewpoints | Oct 21,2023

Fortune News | Jun 24,2023

Verbatim | Jul 27,2019

Editorial | Sep 24,2022

News Analysis | Mar 09,2024

Sunday with Eden | Aug 16,2020

My Opinion | 131819 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128203 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126147 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123767 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...