My Opinion | 129556 Views | Aug 14,2021

May 10 , 2025. By Halima Abate (MD) ( Halima Abate (MD) is a public health professional with over a decade of experience. She can be reached at halimabate@gmail.com. )

Where traditional birth attendants light a small lamp to guide expectant mothers through the dim corridor, in a country that has cut its under-five mortality rate in half over the last two decades, the fragile progress can be undone by a shortage of clean water, a lack of skilled care or a single bout of malaria in a newborn.

Against this backdrop, Abu Dhabi’s philanthropic circles are quietly advancing what they call a “Beginning Fund,” a United Arab Emirates (UAE)-backed initiative devoted to maternal and child health in some of the world’s most challenging environments.

The Emirates have long made global health a focus of soft-power efforts. Behind the scenes, the Reaching the Last Mile (RLM) program has marshalled millions of dollars to wipe out polio and neglected tropical diseases in Asia and Africa. Senior advisers in Abu Dhabi now whisper of a new vehicle, one expressly devoted to mothers and children, the most vulnerable among us. The idea is to deploy money, know-how and technology in tandem, addressing the stubborn causes of maternal mortality, including haemorrhage, sepsis, hypertensive disorders, and the infectious killers of infants, from pneumonia to diarrhoea.

Such a fund could change lives in places like Ethiopia, a country of over 100 million souls where the maternal-mortality ratio is around 400 deaths for a 100,000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate remains stubbornly at 47 per 1,000 according to a 2023 data. Barriers to healthcare in rural and conflict-torn regions are more than distances on a map. Poor roads, weak supply chains, and seasonal floods each act like toll booths on the road to survival.

Ethiopia’s government has laid out its ambitions in the Health Sector Transformation Plan, a five-year blueprint that stresses antenatal visits, skilled birth attendance and community nutrition programs. However, when famine strikes near the Sudanese border, or fighting displaces thousands in Tigray Regional State, the best intentions can evaporate. Health posts often lack basic medicines; midwives float between posts on motorbikes, carrying nothing more than a handful of oxytocin ampoules and a stethoscope.

In Addis Abeba, where public-sector reforms have expanded urban hospitals, the contrasts are evident. Well-staffed delivery wards stand in sharp relief to clinics farther afield. For many rural mothers, a trip to town means a day lost to travel, and for those in more remote villages, it can mean risking exposure. A “Beginning Fund” tailored to such challenges would need more than dollars. It would have to shore up roads, power generators and data networks, alongside the health workers themselves.

UAE planners are said to be interested in partnerships with established actors, including the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNICEF, UNFPA, and even the Gates Foundation, which has co-funded numerous vaccination campaigns in Ethiopia. The idea is to avoid redundant projects duplicating what is already underway. Instead, fund managers would zero in on the "1000-day window," from conception through a child’s second birthday, when nutrition and medical care have the most tremendous lifetime impact.

Among the first interventions would be micronutrient supplements for pregnant women, therapeutic feeding for malnourished toddlers, and improved cold-chain systems for vaccines.

Yet, alignment with the national strategy will be critical for Ethiopia's health policymakers. Programs must fit within our existing structures and respect our priorities. Nothing works if we build parallel systems, without training local midwives, and embedding supply-chain improvements into the government’s own machinery.

Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program already depends on paid volunteers; an influx of outside money could professionalise those roles and ensure that every health post has at least one trained midwife on call. If Ethio telecom can be coaxed into zero-rating health apps - that is, waiving data charges for medical-related traffic - the ripple effects could extend far beyond hospitals, into schools and villages where health literacy remains low.

Still, risks loom. Ethiopia’s unpredictable weather patterns and years of drought followed by flash floods regularly disrupt supply lines. Conflict zones pose even graver threats, where humanitarians warn that access can evaporate overnight when militants or security forces clamp down. Fund managers who fail to design for volatility may find their interventions washed away, literally or politically.

The spectre of inequity also hangs over any large-scale program. Urban centres and moderately accessible regions attract attention, while nomadic pastoralists in Afar or Somali regional states slip through the cracks. To its credit, the UAE’s last-mile programs have tried to map every settlement, helicoptering in supplies where roads do not exist. But that kind of effort can swallow vast sums, and only the most disciplined accounting can ensure that money reaches mothers, not intermediaries.

However, if Abu Dhabi can apply the same rigour to maternal and child health that it applied to its polio campaigns, where global incidence fell by 99pc, then the “Beginning Fund” could prove transformative. Foreign grants often spark domestic budget increases. Under pressure to match high-profile donors, the federal government may find itself allocating more of its own revenues to rural health posts, an outcome long sought by public-finance experts.

More broadly, the health story is a microcosm of Ethiopia’s development aspirations. A generation ago, only one in five rural births occurred in health facilities; today, the figure is closer to one in three. Each percentage point of improvement translates into thousands of lives saved and a healthier workforce. When mothers survive childbirth and infants live past their first year, families build on a foundation that lifts entire communities.

For Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s (Sheikh) donors, the stakes are deeply personal and geopolitical. In speeches at the United Nations, UAE leaders have framed their aid as a moral duty. Last year, the President declared they are guardians of fellow human beings. He told the summit that “when a child’s cry goes unheard, we fail in our greatest mission.”

In practice, the “Beginning Fund” would be a test of that mission.

If it unfolds as envisioned, Ethiopia gains more than injection kits and mosquito nets. It could acquire a blueprint for health-system resilience that weathers shocks and adapts to local realities. In so doing, it would offer the UAE a proving ground for an emerging brand of strategic philanthropy, measuring its value not in headlines or photo ops but in years of life saved and futures secured. In the rough and tumble of global health, that may be the most accurate measure of success.

PUBLISHED ON

May 10,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1306]

My Opinion | 129556 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 125863 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 123875 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 121672 Views | Aug 07,2021

May 24 , 2025

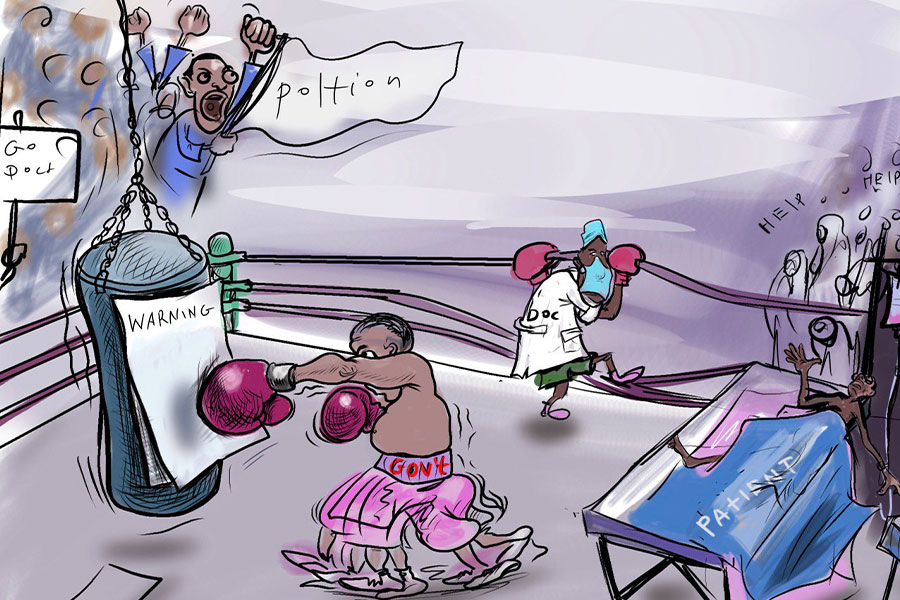

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...

May 10 , 2025

Federal legislators recently summoned Shiferaw Teklemariam (PhD), head of the Disaste...

May 3 , 2025

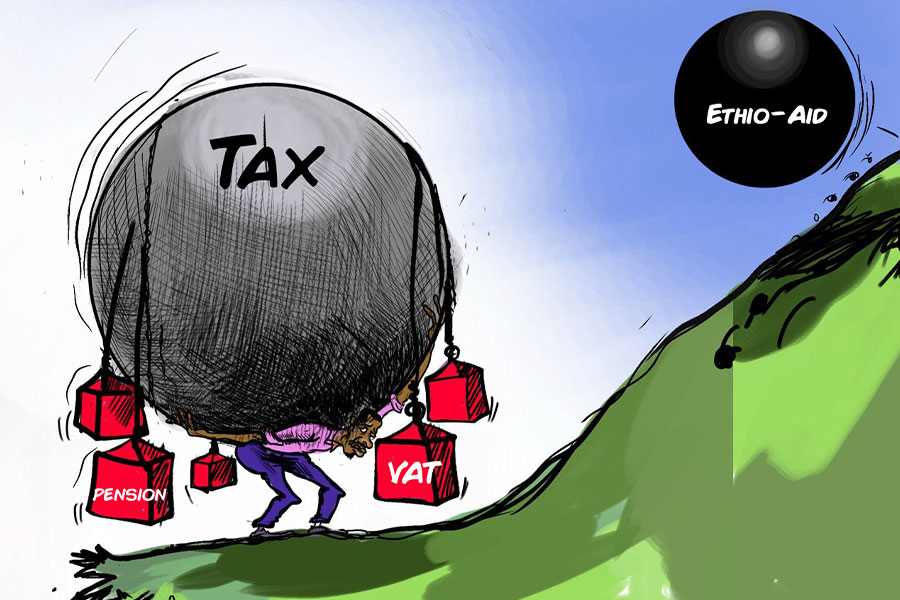

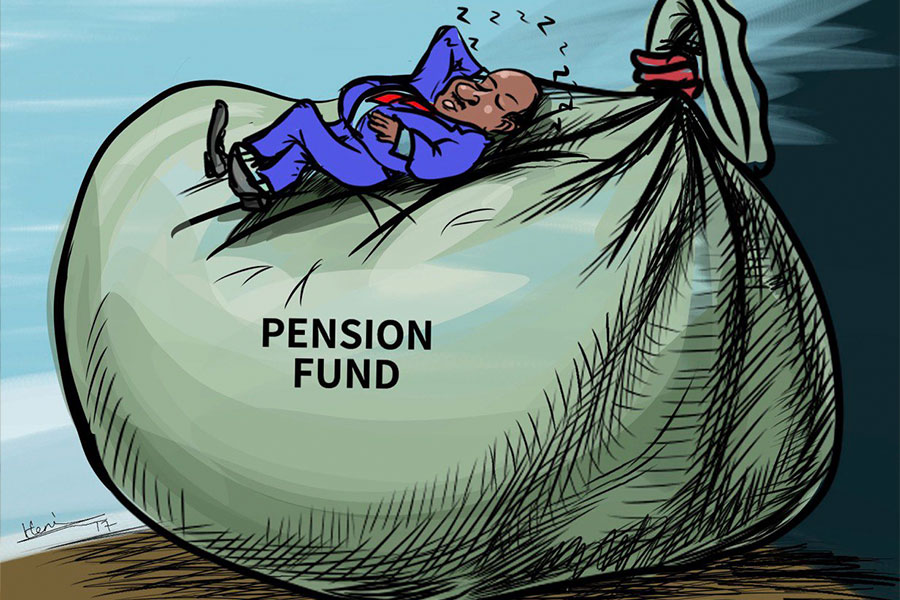

Pensioners have learned, rather painfully, the gulf between a figure on a passbook an...