My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 7 , 2025. By Ahmed T. Abdulkadir ( AhmedT. Abdulkadir (ahmedteyib.abdulkadir@addisfortune.net) is the Editor-in-Chief at Addis Fortune. With a critical eye on class dynamics, public policy, and the cultural undercurrents shaping Ethiopian society. )

When a muggy Tuesday dawns in Addis Abeba, a young driver unlocks a ride-hailing app and hopes, silently, for steady passengers and a generous surge. The compact sedan feels like his own, although the bank holds the title. He sets his hours, or thinks he does, before settling into another 13-hour shift of horns, heat and nasal electronic pings. He would tell riders he is “his own boss,” an idea that evaporates when the algorithm insists otherwise.

Addis Abeba hosts more than 30 ride-hailing platforms. They arranged upward of 90,000 trips a day in 2022, the latest available data, at average fares of nearly 300 Br. Roughly 30,000 to 40,000 drivers chase those trips, earning about 1,400 Br a day before fuel, data, repairs and bank payments. That is above the national average but falls short of a middle-class income once costs are settled.

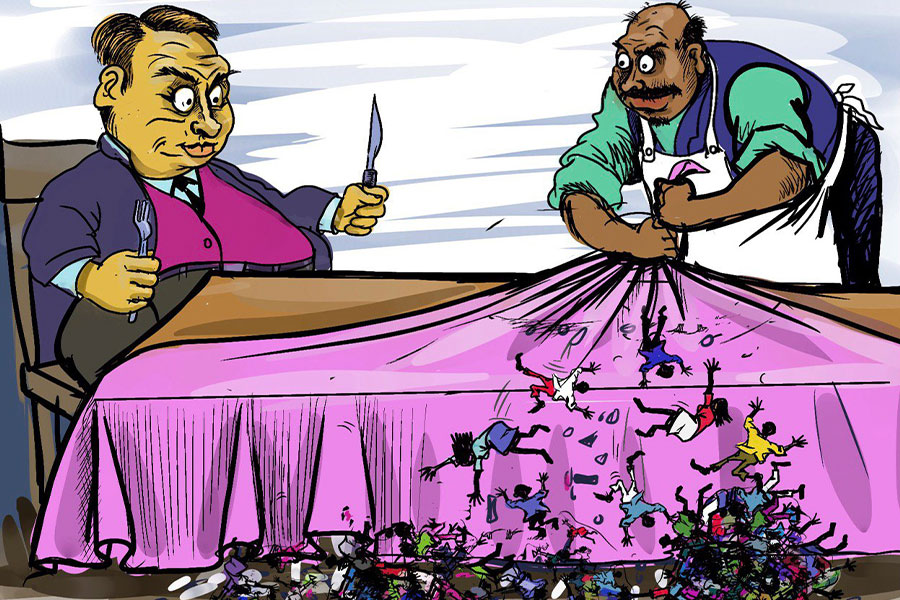

Welcome back to an older order. In medieval Europe, serfs worked fields they did not own in return for the protection they seldom received. In 2025, platform workers labour in digital estates that no one can see and few can question. The stone castles have shrunk into cloud servers, and the lords now speak in software.

The industry advertises freedom, but the shimmer fades on close look. Choosing when to work is not the same as deciding how much to earn, nor does “opting in” create bargaining clout. It is medieval economics dressed for the smartphone age.

Flexibility, the pitch goes, equals liberty. In practice, it means remaining on call, waiting for jobs that may arrive late and pay little. Decline too many rides, and the “acceptance rate” drops. Drive a touch slower or misunderstand a passenger, and the star rating sinks. The rating screen works like a steward of old, noting conduct and handing out rewards or punishments with no debate. If a driver crashes, the risk is his. Perform poorly, or merely appear to, and the app can deactivate the account without notice and without appeal. Workers are labelled “independent contractors” until something goes wrong; then they become cautionary tales.

In the Middle Ages, peasants laboured on a lord’s land and paid rent in crops and loyalty. Present-day drivers obtain access to customers through apps, surrendering a slice of their income, torrents of personal data, and nearly all of their leverage. Platforms provide no cars, fuel or insurance; they supply only a portal. Workers shoulder the liability while the platform claims the heftiest share.

Most apps retain around 10pc of each fare, and food-delivery platforms often take a higher percentage. They refine routes, automate pricing and harvest rich user data, yet offer no benefits. There is no sick leave, accident insurance or pension. The labour code, designed for factory floors and office towers, provides gig workers with scant protection. Many drivers operate without tax licenses, and only a handful of platforms withhold the standard 30pc withholding tax.

Even then, drivers say they rarely see clear statements and have little guidance on recovering deductions or confirming what the government receives.

The appeal endures because choices are few. The youth bulge keeps urban unemployment around 20pc, and smartphone ownership grows each quarter. For many, gig work is not an opportunity, but a means of survival. Freelancers who find projects abroad often rely on services like Payoneer, while PayPal remains out of reach. Banking fees, slow transfers and withdrawal limits nibble at already thin margins.

Yet, the sector remains small. Most Ethiopians lack a suitable handset, a strong data plan and a private workspace. Even among those who qualify, earnings fluctuate so widely that budgeting becomes a matter of guesswork. Risk stays local; reward floats to the cloud.

There is irony in the exchange. Today’s workers do not till soil but mine information. Every ride, route and review feeds the code that controls them. Medieval serfs could not read the charters that bound them; modern drivers cannot inspect proprietary software. Data becomes capital for the platform, while the people who generate it stay in subsistence mode. They have no shares, no co-ownership, and most unsettling, no say. Ratings flash, stress mounts, and user agreements gather digital dust, unread and uninfluenced.

The young driver ends his shift long after dusk, pockets lighter than expected once he settles fuel and loan payments. He would wake tomorrow before dawn, open the same app and hope again for a run of strong fares. Freedom lingers in the marketing copy, but out on the street, it remains as elusive as any medieval dream.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 07,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1310]

My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 126941 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 124945 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 122646 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

May 31 , 2025

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

May 24 , 2025

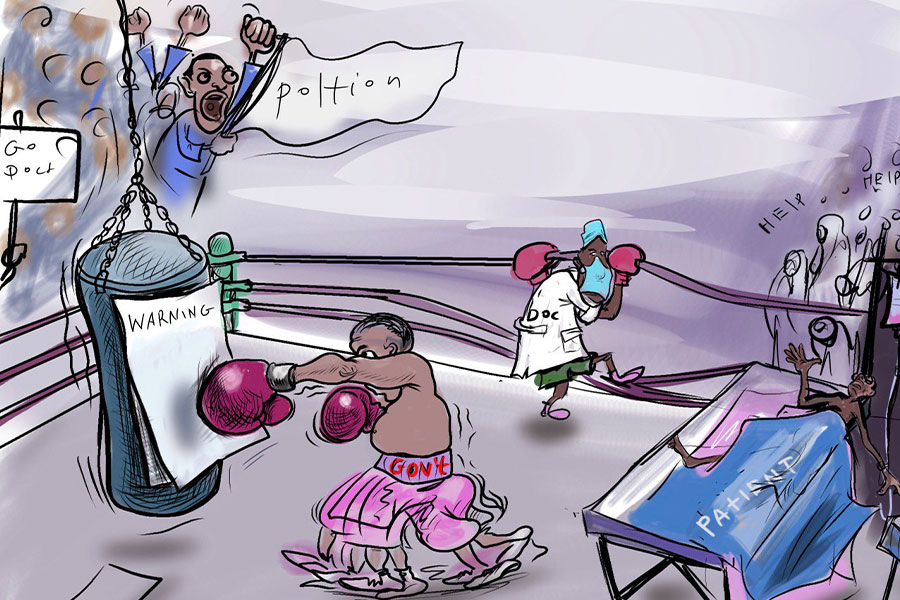

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...