My Opinion | 130254 Views | Aug 14,2021

May 31 , 2025. By Jean Kaseya ( )

Despite being preventable and curable, malaria has continued to claim African lives. In 2023, the continent accounted for around 95pc of the 597,000 deaths from malaria worldwide, 76pc of which were children under the age of five.

But eliminating this scourge, which impedes development goals and the realisation of the African Union's Agenda 2063, is within reach. Nine AU member countries – Algeria, Cabo Verde, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Mauritius, Morocco, the Seychelles, and Tunisia – have become malaria-free, owing to sustained political commitment and well-targeted public investment in primary healthcare, and disease surveillance and case management.

African countries with a higher malaria burden should heed their example.

Algeria, for example, has invested in effective vector control through indoor residual spraying, universal access to healthcare for malaria diagnosis and treatment, and rapid outbreak-response mechanisms. Cabo Verde's strategic malaria-elimination plan involved a multisectoral approach, whereby the government worked closely with local communities and international organisations. Egypt's multipronged strategy included, among other things, robust training programs for primary health workers.

Implementing these coordinated interventions required the political will and, crucially, increased domestic financing.

Overall, Africa's efforts to control malaria – particularly through the use of insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, and seasonal chemoprevention (which involves giving children a monthly course of antimalarial medicines) – have driven a notable decline in malaria deaths on the continent, from 805,000 in 2000 to 569,000 in 2023. (The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the emergence of partial resistance to the well-established malaria medicine artemisinin, caused a brief uptick, to 598,000, in 2020.)

But, these gains are fragile, particularly as new mosquito variants emerge, insecticide resistance grows, climate change worsens, humanitarian crises become more frequent, and, perhaps most importantly, the global malaria-funding gap widens. In 2023, only four billion dollars was mobilised for malaria elimination, far below the 8.3 billion dollars annual target, and a slight drop from the 4.1 billion dollars raised in 2022.

The problem is even more acute in Africa, where external health aid has declined by a whopping 70pc between 2021 and 2025. Most African countries devote less than 10pc of their national budgets to the health sector, well below the 15pc target set by the 2001 Abuja Declaration.

Given the uncertain future of foreign aid, African governments should recognise malaria as a development priority and invest more in efforts to control and eliminate it. That means leveraging untapped resources, including the more than 95 billion dollars in annual remittances from the African diaspora. Innovative financing instruments such as diaspora bonds could support the continent's public health agenda. Solidarity levies on tobacco, alcohol, mobile transactions, and airline tickets could also generate billions of dollars for health services.

Scaling up national health insurance schemes will be required to expand access to malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Blended finance can unlock private capital for malaria-related research and development, as well as local manufacturing of therapeutics. With Africa's healthcare market projected to be worth 259 billion dollars by 2030, policymakers should capitalise on this opportunity to create effective public-private partnerships, advance last-mile delivery solutions, and improve surveillance and vector control.

This would be an investment in Africa's present and future, because every dollar spent on malaria control and elimination generates a remarkable return of 36 dollars in economic growth. A malaria-free population is more likely to access education and contribute to the continent's socioeconomic development. And let me be clear: investing in the fight to end malaria is not only a health and economic imperative; it is an act of justice. The disease disproportionately affects the poorest and most vulnerable Africans, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality.

Last year, I joined health ministers from 11 AU member countries with high malaria burdens in committing to accelerate efforts to reduce deaths from the disease. As part of the declaration, we agreed that "no one should die from malaria given the tools and systems available." The task now is to take concrete action.

The Africa Centres for Disease Control & Prevention is ready to help develop a continental strategy for ending malaria in Africa by 2040. By making smart investments, implementing well-targeted policies, and deepening collaboration, we can ensure that all African countries become malaria-free within the coming generation..

PUBLISHED ON

May 31,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1309]

My Opinion | 130254 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 126554 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 124562 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 122308 Views | Aug 07,2021

May 31 , 2025

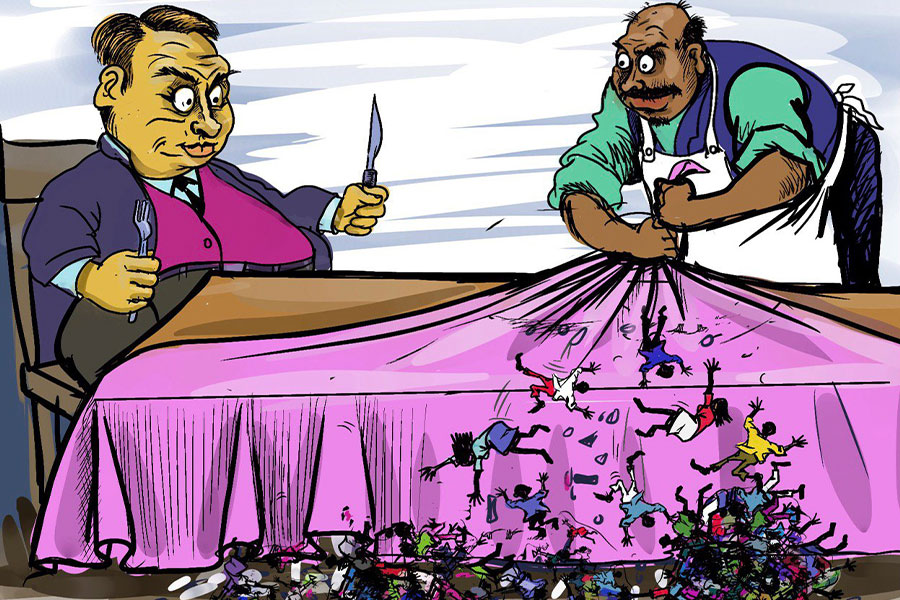

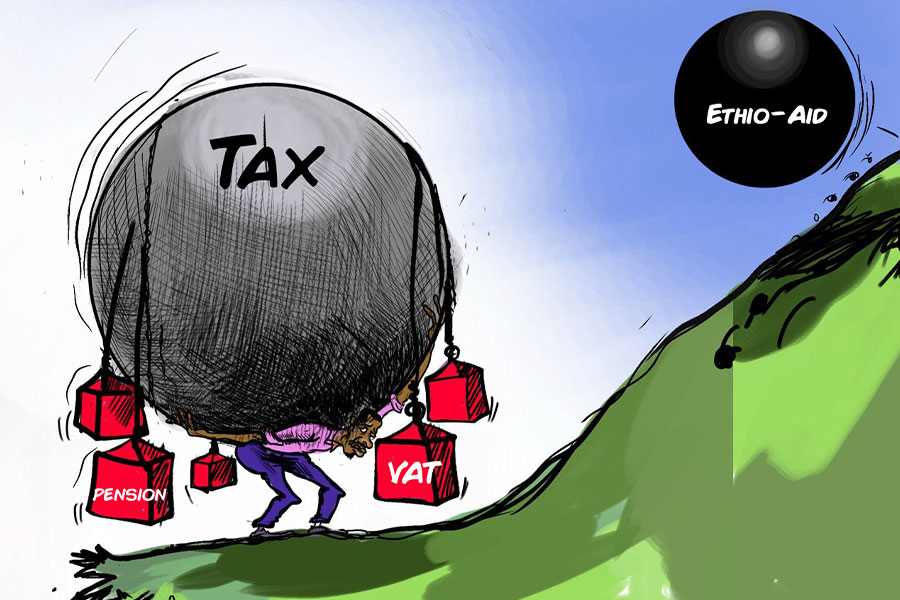

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

May 24 , 2025

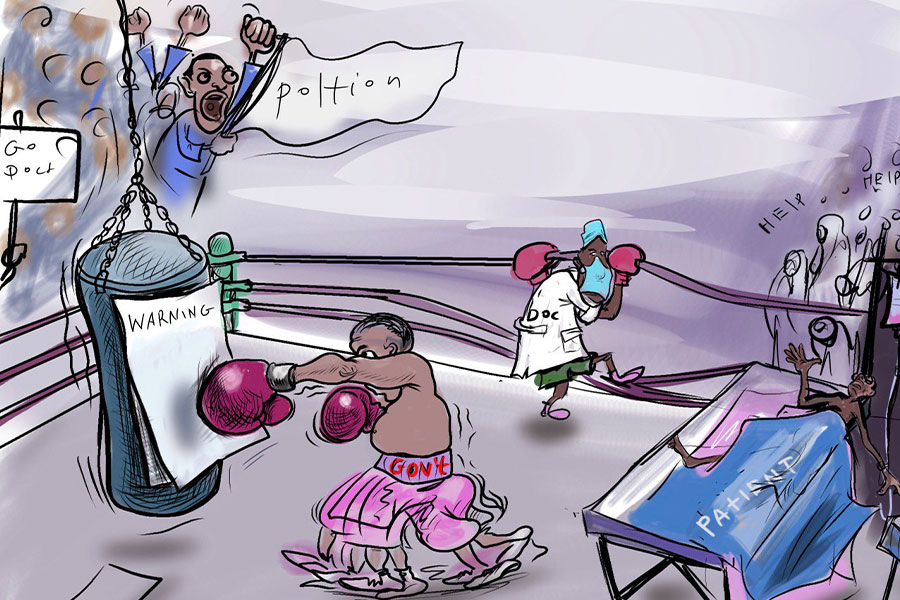

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...

May 10 , 2025

Federal legislators recently summoned Shiferaw Teklemariam (PhD), head of the Disaste...