My Opinion | 133429 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 14 , 2025. By Sisay Lelissa ( Sisay Lelissa (slnegeri@gmail.com) is a development economist studying at Harvard University )

In 2021, I was working on a DFID-funded program in Ethiopia when the cuts came. Overnight, a 21 million pound sterling program was slashed to a mere three million. Staff were laid off, projects cancelled, and promises to communities broken.

What stuck with me was beyond the chaos. It was how easily systems collapsed when external financing dried up. I came to realise that development is not charity. It is about politics and power, and it is a long-term issue.

For decades, governments and agencies across the development community have poured billions into aid across Africa. But after all that time and money, the results still fall short. Perhaps the real question now should be why it has not worked.

The focus here is on development aid, rather than emergency or humanitarian interventions, which play a vital role in crisis response.

Across the continent, aid-funded programs are closing. Clinics are out of service. Ministries that ran on donor budgets are now frozen. Many in the global development sector appear to be caught off guard.

But for some of us who have worked inside the system, the signs were always there. The structure was already fragile. Germany, once among the world’s most generous donors, has cut 5.3 billion dollars in aid since 2022. The United Kingdom (UK), following its 2020 merger of the Department for International Development (DfID) with the Foreign Office, reduced aid to 0.5pc of national income, triggering a 33pc cut to Africa programs by 2021.

Now that aid budgets are shrinking, the weaknesses are more visible.

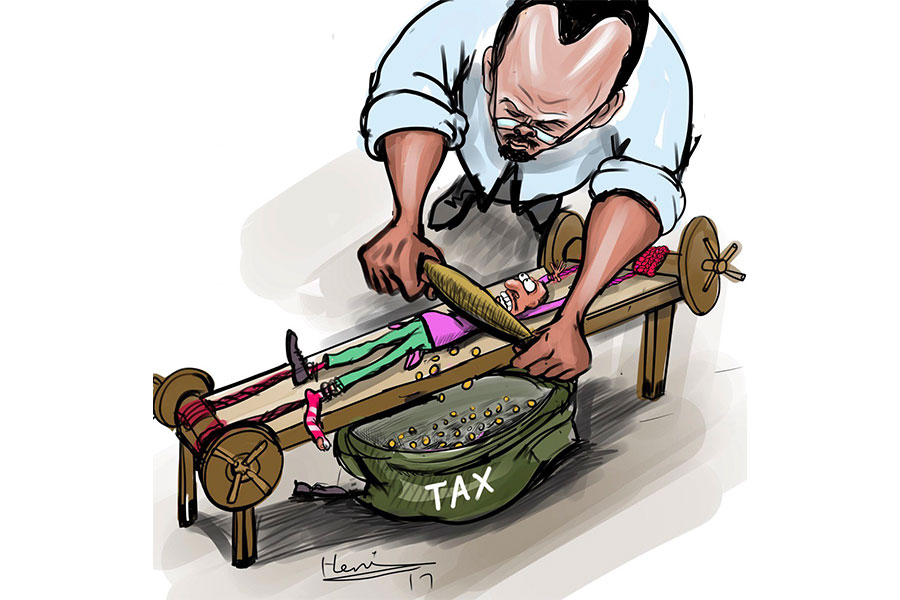

From the beginning, I have always believed the model has been a contradiction. Countries are expected to take ownership of systems that someone else designs and pays for. Ministries are asked to be accountable to citizens while foreign grants fund their programs. Governments are measured on the “sustainability” of projects that cannot survive a single funding cut.

The result is systems that look functional on paper but collapse as soon as external financing stops. Projects that deliver services but do not establish the necessary institutions to sustain them. This is not only about poor implementation. The problem is with how the system was built. It is time the development community faces that truth.

Donors’ flags are visible on vehicles, schools, hospitals, buildings, and even water tanks. Some donors even request a portion of the budget to be allocated toward visibility, such as billboards, banners, and branded notebooks. The whole package may not be only for show. But it reflects who is shaping priorities.

In Malawi, even core government institutions reflect the dominance of donors, as “The Economist” put it, many health ministry offices are “labelled by donor, not department.”

Development agencies have not only financed programs; they have also implemented them. They have run them. They have written the strategies and the projects, hired the consultants, and led implementation. Then, when results fall short, they are also the ones writing the evaluation.

That has been the real problem. The development community has not simply supported development. It has tried to direct it. Local governments are left in the shadow of donor mandates.

Inside the system, what gets lost is a genuine reflection of what is working on the ground. And, in a system like this, honesty can feel risky, and disclosing the truth might cost you the next round of funding.

If the development community truly wants to support progress, maybe it is time to stop trying to do it directly. Instead, there is space to enable trade. To unlock investment. To help African innovation with access to markets, capital, and technology.

Trade barriers keep African products out of global markets, and value addition is often penalised through tariff escalation.

The European Union (EU), for example, allows countries like Ghana or Côte d’Ivoire to export raw cocoa beans duty-free, but imposes tariffs of up to seven to 15pc ad valorem duty on cocoa powder and chocolate crumbs containing cocoa butter. This discourages local manufacturing and keeps African economies stuck at the low end of global value chains.

Massive subsidies in Europe allow European farmers to sell food at artificially low prices, undercutting African farmers even in their own domestic markets. Investment in African startups remains limited, although models like the Timbuktoo Initiative, although still in its early stages, offer a glimpse of what is possible when global institutions act more like venture partners than traditional donors.

Regional infrastructure is still underfunded. The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), the continent’s most ambitious trade project to date, requires technical, financial, and political support to succeed.

Addressing these issues would go a long way in opening new markets, building supply chains, and creating long-term opportunities for donor countries themselves. Such partnerships can still be win-win, sharing both risk and reward. Not the kind buried under fancy logframes and layers of donor conditions that hardly anyone reads or even understands.

Donor agencies can still play a role, but it is not the one they have been playing. Their job is not to implement. It should be to facilitate, connect, and get out of the way when governments do their job.

The G20 Compact with Africa presents a more effective model. It does not deliver aid directly or run programs. Instead, it supports African governments in strengthening investment frameworks, de-risking private capital, and attracting long-term financing. Yes, it still promotes reforms, but they are shaped through mutual agreement and in line with national priorities.

In Ghana, for example, the Compact backed legal reforms and infrastructure development without donors in the driver’s seat. Ethiopia’s prospectus, presented under the same platform, speaks in the language of opportunity, infrastructure, energy, and skills, rather than poverty or despair.

Development partners should focus on enabling regional coordination, bridging the gap between governments, and backing high-potential sectors. They should not be managing ministries through parallel “implementation units” that do not see themselves as working for the government but are accountable primarily to donors or tracking success by the number of technical assistance missions they have flown in.

Much of the development model has created an “outsourced state,” where core government functions are delivered through donor-funded projects. Progress is judged by compliance with externally set targets rather than outcomes that matter to citizens.

Let us be honest. The system is outdated and needs a new framework. One that creates a win-win for both donors and recipient countries. Development aid should not be seen as simply “helping” and both parties should recognise it as such.

This is where economists, researchers, and practitioners should step in, and now is the ideal time. They are not only there to critique what is broken, but to help design something better.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 14,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1311]

My Opinion | 133429 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 129943 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 127749 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 125303 Views | Aug 07,2021

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....

Aug 2 , 2025

At daybreak on Thursday last week, July 31, 2025, hundreds of thousands of Ethiop...

Jul 26 , 2025

Teaching hospitals everywhere juggle three jobs at once: teaching, curing, and discov...

Jul 19 , 2025

Parliament is no stranger to frantic bursts of productivity. Even so, the vote last w...