My Opinion | 133317 Views | Aug 14,2021

Aug 9 , 2025.

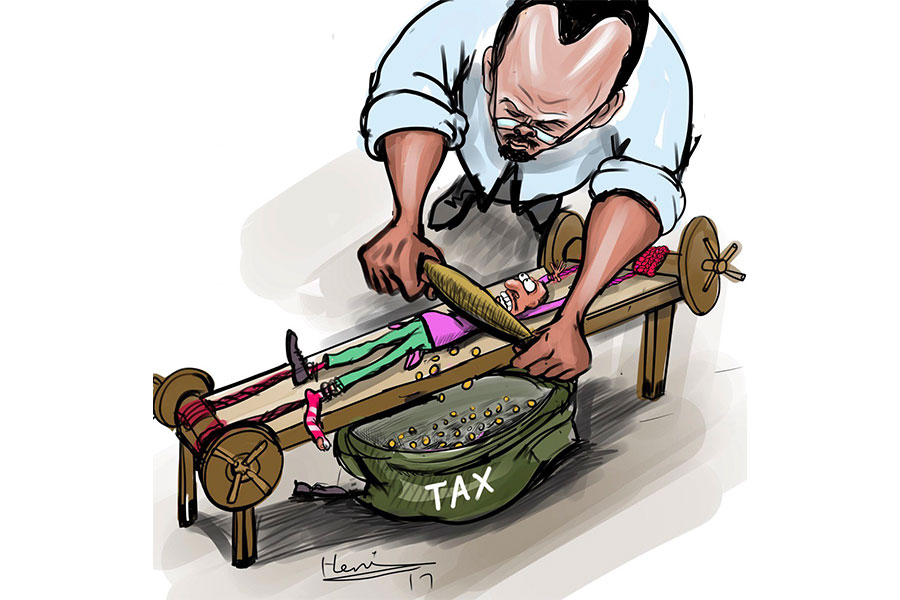

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand. Young dynasties, he observed, can fill their coffers with modest taxes, but ageing ones squeeze ever harder for diminishing returns. Six hundred years later, Arthur Laffer sketched the same idea on a napkin. Revenues start at zero when tax rates are nil, peak somewhere in the middle and subside back to nothing at 100pc.

Contemporary Ethiopian policymakers now find themselves perched on that curve, chasing revenues of 1.5 trillion Br. They have rewritten the income-tax law to push collections up from what, even by African standards, is a meagre take in relation to GDP. They should worry that higher rates may yield smaller returns as they risk forgetting what shapes people’s capacity to pay.

Ethiopia may appear to be a single economy, with unified monetary, fiscal, exchange-rate, and tax structures. Look harder, and the fabric is fraying.

Start with money. In July 2024, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) abandoned its cumbersome credit quotas in favour of an interest-rate corridor, designating the overnight interbank rate as its operational target. By October, a fully fledged interbank market had sprung to life, designed to meet the liquidity needs of every bank. Interbank and Treasury-bill yields soon rose above inflation, the first genuine nationwide transmission of monetary impulses.

But the transmission remains partial. Rate changes resonate in a handful of big banks headquartered in Addis Abeba, while rural lenders and micro-finance outfits, marooned in shallow markets, continue “evergreening” loans and barely budge their prices. The Central Bank’s levers pull on the capital, while the periphery runs on local liquidity rhythms.

Treasury cash flows reveal a similar patchwork. Regional governments now conduct more than half of public spending, yet their own revenues cover scarcely a third of their mandates. The federal grants intended to level the playing field rely on outdated data that flatters some regional states and starves others. Some states run perpetual deficits and seek ad-hoc borrowing approvals, behaving like mini-economies with distinct fiscal cycles.

Tax enforcement is equally uneven. On paper, Ethiopia has a single code, but in practice, it has several. Value-added tax compliance reaches 80pc in Oromia Regional State, but tumbles below 40pc in Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regional states, and remains over 90pc in the capital. Corporate-income receipts track local zeal as much as legal rates. The patchwork hosts multiple fiscal micro-systems, each with its own health.

When the Central Bank attempted to unify the official and parallel markets, the premium widened, reaching above 170 Br to the dollar last week. Researchers have demonstrated that the gap is influenced by trade openness, crop output, and public-sector corruption, rather than geography. Yet, in practice, parallel rates diverge, with border towns and rural hubs quoting markedly different spreads. Areas flush with diaspora remittances enjoy premiums 10 to 15 percentage points lower than regions with weaker links. A recent Central Bank injection of 150 million dollars into the auction system barely rippled beyond big cities.

A national economy can scarcely function without shared stabilisers. The federal budget, now aligned with a National Medium-Term Revenue Strategy, tries to harmonise regional incentives. Formula-based transfers, recalibrated annually, are designed to reflect shifts in borrowing, spending, and revenue across the federation. However, the formulas update rarely, and a meaningful equalisation remains elusive.

Faced with these fissures, policymakers may be tempted to reach for standard blueprints, most likely copied from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) playbooks. It would include, but not be limited to, strengthening institutions, deepening markets, and widening the tax base.

Undoubtedly, these fixes matter. Medium-term fiscal frameworks, modern forecasting, and digital data (from e-payments to social registries) could indeed sharpen stabilisation and disaster response. A professional policy-analysis unit at the Central Bank, along with legal autonomy for its rate-setters and the publication of monetary committee minutes to the public and market actors, would anchor expectations. The tax authority could harness data analytics, streamline exemptions, and plug VAT and income tax leaks.

Phasing out credit caps, dematerialising government securities and building a secured repo market would give the economy a yield curve and anchor short-term rates. A thorough map of the foreign-exchange hinterland could enable the Central Bank to save its dollars for truly disorderly episodes while allowing more flexibility the rest of the time, thereby shrinking the premium. A national disaster-risk fund and rules-based limits on regional borrowing can help impose discipline and smooth shocks.

Even the neatest frameworks buckle unless the revenue base broadens. A recent study recommends tighter VAT exemptions, stricter excise-stamp checks, and full implementation of the revenue strategy to bring the tax-to-GDP ratio up to peer norms. Benchmarking potential and coaxing small firms from the shadows would make income taxes track growth more faithfully.

However, these policy remedies, though worthy, may not be enough. Extraordinary times call for fresh tools.

One is to legalise community finance co-operatives rooted in "Idir" and "Iqub," the traditional rotating savings clubs. If given modest access to the Central Bank's liquidity at a spread above the policy rate, and embedded in mutual-guarantee schemes, they can be instrumental in funnelling funds to micro-enterprises and small farmers. In doing so, they can convey monetary signals that commercial banks do not typically provide.

Another novelty could be the establishment of peer-to-peer foreign-exchange hubs in regional capitals and border towns. Tapping diaspora and farming co-operatives, the hubs could match buyers and sellers through mobile money rails. Smart-contract auctions, run by simple SMS, could publish bids and offers, trimming the spread between the official and parallel rates while honouring local diversity.

A Central Bank Digital Birr used in cross-border payments could sidestep capital controls. A “digital lockbox” would convert remittances instantly into local money, funnelling diaspora savings to domestic lenders. A narrow trading window for convertible tokens would undercut smugglers, illuminate flows and let the Central Bank gauge pressures in real-time without opening the floodgates.

Raising revenue without revolt might rest on a visible “social dividend”. Small levies on mobile-money transfers could be allocated to a ring-fenced fund for clinics, schools, and roads, disbursed through participatory budgets at district assemblies. Citizens would see the link between taxes and services, turning compliance into a vote of confidence.

True fiscal federalism need not wait for perfect equalisation. The federal government could test competitive performance grants through “innovation endowments” for states that meet targets on vaccinations, school completion, or clean water. Tying cash to results designed with local councils would unleash peer pressure and replace handouts with shared ambition.

These ideas may eschew one-size-fits-all templates. However, they build on community bonds, outcome-driven grants, digital platforms and participatory checks. They do not throw out prudence, but insist that policy be felt in villages as well as boardrooms, that markets be partners rather than targets.

Contemporary Ethiopia feels like a federation of disparate fiscal and financial micro-systems, each charting its own currents under the illusion of a single economic community. However, a coherent national macroeconomy remains more ambition than fact. If officials hope to climb the Laffer Curve rather than tumble down its far slope, they should knit those fragments into a single fabric. Otherwise, heavier levies will indeed harvest thinner yields, as Ibn Khaldun warned, and Ethiopia’s grand revenue quest will remain a mirage.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 09,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1319]

My Opinion | 133317 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 129828 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 127645 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 125193 Views | Aug 07,2021

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....

Aug 2 , 2025

At daybreak on Thursday last week, July 31, 2025, hundreds of thousands of Ethiop...

Jul 26 , 2025

Teaching hospitals everywhere juggle three jobs at once: teaching, curing, and discov...

Jul 19 , 2025

Parliament is no stranger to frantic bursts of productivity. Even so, the vote last w...