My Opinion | 128232 Views | Aug 14,2021

Apr 27 , 2025. By BEZAWIT HULUAGER ( FORTUNE STAFF WRITER )

As officials race to build more schools and improve facilities, the core issues persist: overcrowding, insufficient resources, and the struggle to maintain quality. When families find themselves adrift in new neighbourhoods without support, the ripple effect touches every aspect of their lives, reports BEZAWIT HULUAGER, FORTUNE STAFF WRITER

Takeaways:

Hana Melaku, a mother of two, had never imagined life outside Cazanchis. One of the historic neighbourhoods of Addis Abeba, it had been her world from birth, a place stitched together by familiar faces and steady rhythms. But a few months ago, she and her family were resettled, carried by the winds of relocation to a condominium unit in a newly established vicinity popularly known as "Ayat 49."

The move was supposed to be a step forward, a new beginning. Instead, it has left her disoriented and struggling.

Their new home, stark and unfinished, greeted them with missing windows, doors, and no electricity. Although most power issues have been fixed, 33 households still share a three-phase switch, a daily source of tension that is aggravated by a steep 6,000 Br top-up system every two weeks. Social life in the new place feels frozen. Neighbours pass by without a word. Shops and clinics are few and far between, a sharp contrast to the tight-knit and accessible community Hana had always known.

But more than anything, it is her daughter, Mekdelawit Abreham, who weighs most heavily on her mind. At seven, Mekdelawit now squeezes into a packed public school classroom, sharing a desk with nine other children, surrounded by as many as 105 classmates.

"She is not learning anything," Hana said, her voice low and tired.

Before they moved, Mekdelawit had attended a private school. It was a different world then, with small classes, patient teachers, and space to dream.

That all ended when Hana, unable to find work after the move, could no longer afford the fees that private schools in the new neighbourhood charges. Now, she relies on her husband’s income, while Mekdelawit returns home each day with dirt-streaked clothes and an increasingly vacant stare.

"I always find her dirty," Hana said. "Her excitement for school is just gone."

The transition has been all but smooth. It took Mekdelawit a month after the move to secure a spot in a school. Since then, her grades have slipped, and her disinterest has grown more evident by the day. Hana leafs through her daughter’s exercise books and finds them untouched, homework uncorrected. Teachers seem as overwhelmed as the students. Hana dreams of returning her daughter to private education, but until she can find work, that dream remains out of reach.

Hana’s story is far from unique.

In the view of the city's officials, the mass relocation that moved tens of thousands from places like Cazanchis to far-flung outskirts, such as Gelan Gura, was part of an effort to address Addis Abeba’s "renewal" and growing housing shortage. Up to 5,000 households from the Kirkos District were relocated on the southern outskirts of the capital. This has stretched the infrastructure to breaking point.

According to Addisu Shanko head of Kirkos District, the city administration had provided enough schools.

Two schools sit within a kilometre: Gelan Gura Primary and Secondary schools, One and Two. The second school, built specifically for relocated families, is still not fully operational, leaving the first school overwhelmed and operating beyond its capacity.

Teachers like Bersistu Buhuja paint a picture different from the one portrayed by the officials. Handling a KG3 class of 70 students, she struggles to give each child the attention they need. Preparing homework for all her students often means she has to skip lunch entirely.

"Parents get upset when we don't give the students homework," she told Fortune. "To give them homework, I've to skip lunch."

Bersistu has been teaching for 14 years and says she has never seen congestion like this. She finds it almost impossible to evaluate students fairly. The surge, she believes, is fuelled by relocated families and by others moving to the area for lower rents.

Classroom overcrowding is more than an inconvenience. It is quietly undermining students' educational future. Official standards dictate that there should be no more than 40 students in a class. Yet, at places like Ayer Tena Secondary School, over 4,000 students are packed into 71 classrooms, with some rooms cramming in as many as 87 students.

Even essential resources are missing. Science laboratories, where they exist, are poorly stocked. Materials vanish or are used up after a few experiments. According to the Principal, Meberatu Weldegebreal, the crowded conditions feed directly to poor exam results. Last year, only 5.6pc of Ayer Tena’s more than 1,000 Grade 12 students passed straight into university. Only 66 students made it, while 234 needed remedial programs.

To make up for lost ground, tutorials are now run on Saturdays and after regular hours.

"It's hard to see them pass, as they were poorly taught in lower grades," Meberatu said.

Since 1994, Ethiopia has made remarkable strides in access to education. Primary school enrollment has soared, increasing fivefold to over 14 million by 2019. Secondary school numbers have doubled. The country’s Gross Enrollment Rate now nears 96pc, matching that of some middle-income countries.

But, gains in access have not translated into quality. Studies show that overcrowded classrooms and poor student-teacher ratios can negatively impact learning outcomes. For Grades one to eight, the average pupil-to-section ratio is now 50.1 to one. Dropout and repetition rates remain troubling: overall dropout is at 17.9pc; and in middle schools, the repetition rate hits 11.6pc, compared to three percent for primary levels.

Furi Primary & Middle School is another frontline in this battle. With 2,400 students and as few as 128 teachers, classrooms hold up to 70 students at a time. Habtamu Taffese, the deputy principal, admitted that class sizes breach standards but believes denying students access was "unthinkable."

Even here, problems have surfaced. Last year, allegations of over-registration and fraud engulfed the school, leading to ongoing legal action, according to Zenebech Molla, secretary of the Parent-Teacher Association. Nonetheless, somehow, Furi boasts impressive exam results: a 100pc pass rate for Grade Six, and 99pc for Grade Eight. Zenebech, reassured by the school’s performance, remains hopeful about her children’s education.

Habtamu attributed the success to relentless result analysis and focused tutorials. So is the pressure no less stubborn. Overcrowding makes student-centred teaching, proven to be 95pc more effective, almost impossible. Teachers default to lecture methods to survive 45-minute sessions.

Habtamu has noticed something else too: students studying in smaller Afan-Oromo language classes consistently outperform their peers in larger classes.

The city recently introduced a standardised continuous assessment system, affecting more than 2,000 schools and 1.2 million students. The idea is to move beyond final exams and focus on creativity and engagement throughout the year. But, for overstretched schools, it is another administrative burden on top of everything else.

Night classes offer little respite. Teachers are paid a mere 1,000 Br for these sessions and still face the same overcrowded and poorly resourced conditions.

At Akaki Qality Secondary School, the challenges are no less daunting, where 40 of the 122 teachers have completed postgraduate studies. New curriculum demands, such as career and technical education (CTE) and visual arts, have created gaps that schools are struggling to fill.

"We assign biology teachers to teach agriculture," said Alemayehu Duressa, the school’s deputy principal.

Basic needs go unmet. Textbooks for Amharic and Afan-Oromo are missing. Textbooks for career and technical education are often available only in digital format. Facilities are dire. Only one toilet functions for every 163 students, and frequent water shortages have shut down laboratory activities. There are no sports grounds. Only 38.7pc of schools across the country have a functioning library; and 10.9pc have laboratories. While 90.6pc report having toilets, only 37.8pc meet acceptable standards.

Last year, 22 out of Akaki Qality's 280 students passed the national Grade 12 exam. Ninety others entered remedial programs. Many simply opted for private colleges or jobs instead of pursuing higher education.

Still, enrollment at the school is rising, pushed up by relocated families and a nearby newly established military facility. The student population now is 1,900.

To confront the problem, the Addis Abeba Education Bureau is racing to expand capacity. Thirteen new schools have been built, 256 old schools renovated, and 77 more projects are underway. The city has a student population of 1.3 million, with a little over half attending public schools. Yet, with 1,600 private institutions out of 2,200 schools, private education remains dominant and is largely unregulated, with fees.

Nationally, 85pc of schools are considered below standard. The Ministry of Education has launched the “Education for the Generation” movement, raising a total of 81 billion Br and 54 billion Br this year to fund the construction of 6,815 new schools and improvements to tens of thousands more.

But not everyone is convinced that building more schools will fix everything.

According to Fitsum Gebremichael, a PhD candidate in education policy at Addis Abeba University, overcrowding is not the only part of the problem.

"It can't be considered the sole reason," he said, pointing to students’ readiness to learn and the quality of the curriculum as equally important factors.

Fitsum stated the need for counselling and remedial support when families, such as Hana's, are relocated, warning that disrupted students often lose their motivation.

"Students who aren't motivated can't score any better," he told Fortune.

Despite everything, there are glimpses of hope. Fitsum praised schools like Furi for using creative assessment methods to improve learning outcomes even under tough conditions. If more schools follow their lead, the future of young learners may yet brighten.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 27,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1304]

My Opinion | 128232 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 124463 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 122557 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 120405 Views | Aug 07,2021

Apr 26 , 2025

Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that “nothing is certain but death and taxes.�...

Apr 20 , 2025

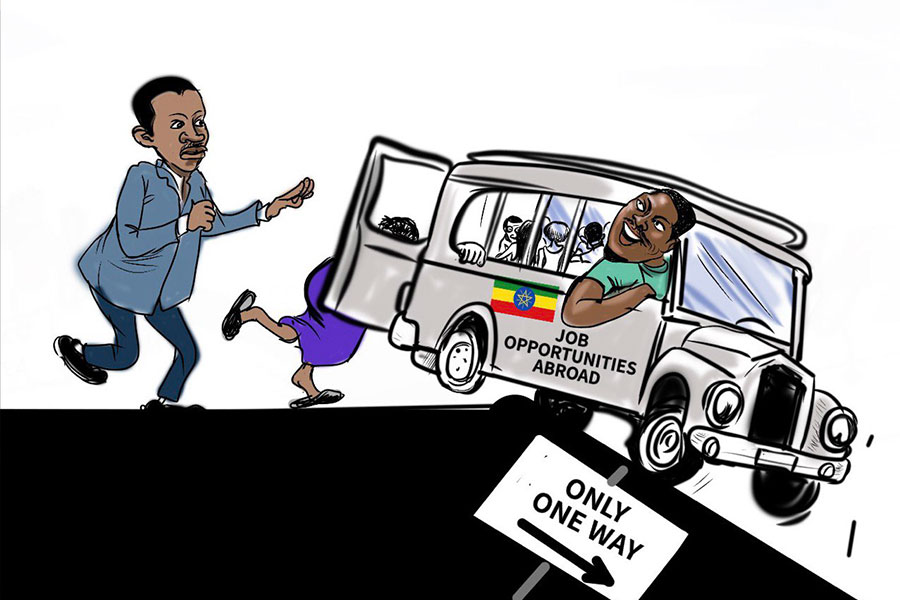

Mufariat Kamil, the minister of Labour & Skills, recently told Parliament that he...

Apr 13 , 2025

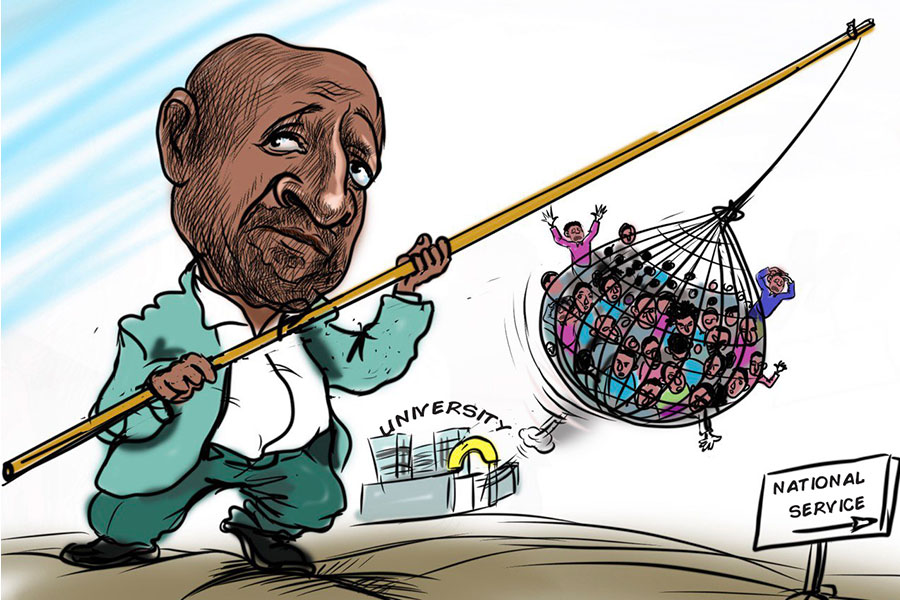

The federal government will soon require one year of national service from university...

Apr 6 , 2025

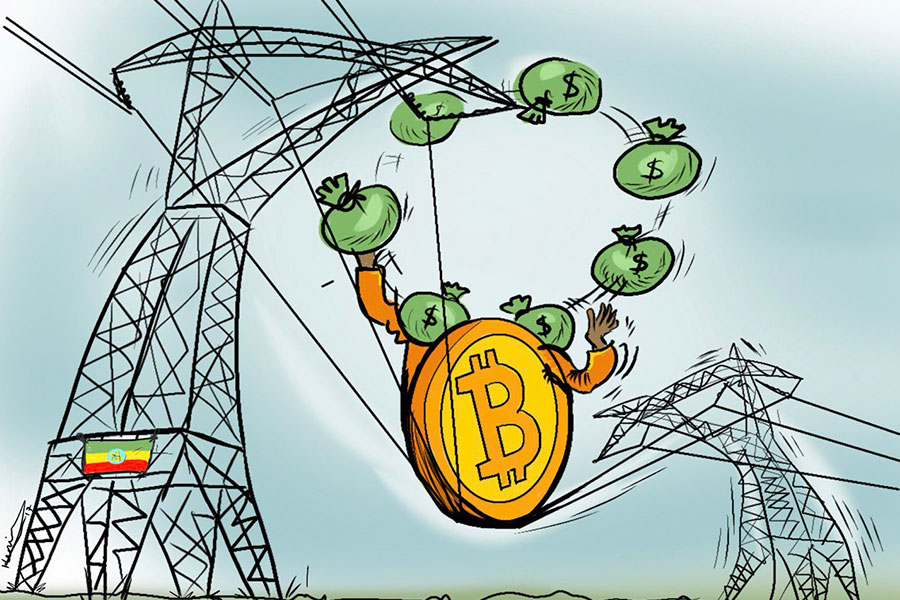

Last week, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group...